“Because a man who doesn’t spend time with his family can never be a real man.”

Screenplay by Mario Puzo and Francis Ford Coppola

“Because a man who doesn’t spend time with his family can never be a real man.”

Screenplay by Mario Puzo and Francis Ford Coppola

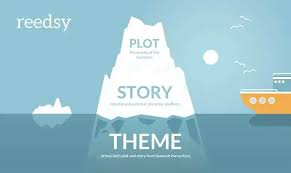

What is your story about? Don’t tell me it’s about a guy who robs a convenience bank to get the money to pay for his daughter’s cancer operation. Tell me it’s about income inequality and the lack of affordable healthcare. That is the difference between story and theme. Even though they’re different, they play off each other and feed off each other. In order for the story to be great, the theme must be powerful.

I have heard many people compare themes to morals. Is the theme the moral of the story, like from an Aesop’s Fable or a Brothers’ Grimm Fairy Tale? In its most simplistic form, the answer is yes. However, there should be more to it than that. A message can be a part of a higher moral idea stating you shouldn’t do this or you should do that. The idea of a theme goes deeper than that, however. A theme gives a story a point of view. It tells the audience they’re seeing more than something that will entertain them. It will inform them. It will make them look at an issue with a new perspective. It will challenge them in ways that may be unexpected.

A screenplay’s theme often directs us to how we feel about the film we’re watching. Movies are at their most powerful when they elicit emotional responses. Having a powerful theme is one way to stir up that emotion. Think about the idea mentioned above. A story about a man robbing a bank suggests ideas of action and suspense. The script could be a thriller, or it could be a drama. Movies like Dog Day Afternoon or Heat come to mind. However, once you add the idea of income inequality and the lack of affordable healthcare driving a man to desperation to save his daughter, the idea becomes its own. It becomes a unique and fresh idea about fatherhood, family, equity, and humanity. Those are emotional ideas that bring depth to a story that will further engage your audience beyond the surface level of what they’re seeing on screen.

Adding subtext to a screenplay is one of the most difficult skills for new screenwriters to develop. Adding strong thematic components to your script is one way to add subtext to your arsenal. Subtext is the art of implying ideas without directly stating them. The best dialogue is written with subtext. It makes the dialogue feel more natural and adds depth to the characters and their relationships. In the overall story, the theme should come across in a subtextual way. No character should ever have to come out and say, “I wouldn’t have to rob this bank if it wasn’t for the insurance company denying my claim!” That point should be made by the action, the relationships, and the flow of the story. If the screenwriter and the filmmakers do their jobs properly, the theme of the story, the writer’s point of view, and the story’s emotional context should be obvious to the audience.

The lessons that we glean from stories, however subtly they’re delivered, provide the stories’ emotional spine. We need to care about what the protagonist cares about. What the protagonist cares about is generally reflective of the story’s theme. The protagonist’s growth is also reflective of the theme. The protagonist often starts the story with certain attitudes and beliefs, which often change over the course of the story as the protagonist learns and grows. Depending on how likable the protagonist is, the audience should root for the protagonist to make the changes she needs to make to become a better person and ultimately accomplish her goal. What the protagonist learns, we should also learn.

Do all screenplays have significant thematic elements? No, they all don’t. However, using them will almost always make your script better. If you’re writing a genre picture like a straight action film, a comedy, or a horror movie, you can get away with omitting strong thematic components. But even genre films work better with them than without them. Think about your favorite genre films. There’s a good chance that even your favorite action film, comedy, or horror movie has some thematic component that sets it apart from the run-of-the-mill entries into that specific genre.

A movie’s prime directive should be to entertain. Some films are made to inform, others to expose a particular point of view, but all movies should elicit an emotional reaction from the audience. Presenting a point of view, some kind of lesson to learn, or the idea of growth from believing one thing to believing something else facilitates that emotional engagement by giving the audience something to care about. A movie’s theme ultimately provides that emotional engagement.

“You keep dancing with the Devil, one day he’s gonna follow you home.”

Screenplay by Ryan Coogler

Some of you may be familiar with GenXvZ: A Movie Podcast, which I co-host with my daughter, MacKenzie. We are both film school grads, and we review current films and discuss what we believe makes them great or what caused them to miss the mark. A common refrain that is often heard in our podcast is the lamenting of original material in cinema these days. We all know we’re constantly being force-fed tentpole content from sequels or franchises that have done a lot to suck the joy out of cinema over the past decade. Unfortunately, when studios have taken risks with new or original material over the past couple of years, it seems that those efforts have been met with collective yawns from audiences.

Sinners has been in theaters for 10 days and it has raked in a whopping $122.5 million domestically and $161.6 million worldwide. It had an opening weekend box office total of $48 million, and it only dropped 6% on its second weekend for another massive haul of $45 million.

Sinners was written and directed by Ryan Coogler (Black Panther, Creed, Fruitvale Station), a director who has demonstrated equal comfort in the franchise, indie, and blockbuster spaces. He has directed some of the biggest box office hits of all time and is one of the most critically acclaimed filmmakers of his generation. With Sinners, he moves into the Horror genre, using his impeccable filmmaking style to craft a film that is entertaining while also being thematically deep with elements of racism, social justice, friendship, family, and ethics brought to the forefront of the storytelling. This is a graphically violent film that isn’t gratuitous. This is a sexy film that is tasteful. Most importantly, this is a fantasy film that is honest.

I believe Sinners is resonating with audiences so effectively because this is a movie about people. That might sound like a simple statement, but one of my problems with the horror genre is that the characters are rarely people: they’re meat puppets. They’re characters lining up for the slaughter. You might care about one weak girl that you hope will get away, but you’re rarely emotionally engaging with anyone. The best horror movies, such as Dracula, The Shining, Misery, The Silence of the Lambs, and Get Out, all feature protagonists we care about. They’re deep characters with pathos, inner demons, or outer needs that we can relate to. The rest are just slasher movies. “Sinners” joins the pantheon of great horror movies because it gives us the same qualities those other great films gave us as well.

Sinners is also an exceptionally well-made film. Coogler wrote the screenplay and directed the film, and he brought out all the stops to make this a fantastic film. His use of long takes heightens the drama and the suspense. His lighting heightens the mood. The story’s pacing keeps us riveted and on the edge of our seats.

It should not be understated that Coogler is African American, as is Michael B. Jordan, the film’s biggest star. Almost the entire cast is made up of people of color, with the exception of the antagonists, who are all white. The symbolism in this film is clear, and yet it has found a wide audience that, by all accounts, crosses all demographics. In a time as divisive as the one we’re currently living in, the fact that a film with such a diverse cast can be made and be as successful as it has is as encouraging as any other positive news this film’s success brings.

Additionally, there is a message in the casting. The message isn’t that all white people are monsters and that the only good people are people of color. That’s where the depth of the story makes its greatest impact. The white people are also vampires. They didn’t start out that way. They became vampires because they were attacked by other vampires. Similarly, no one is born racist. People become racists by being taught and raised by other racists. Monsters aren’t born, they’re created. That is one of the driving messages of the film, and that type of symbolism is an example of what separates Sinners from other horror movies.

If you have not seen Sinners yet, please make it a point to do so. This is the type of film that cinema fans must support, not only for the writers and directors who make the films, but also for the studio executives to see that investing in this type of material can be profitable.

“I am what God made me.”

Screenplay by Peter Straughan

The Ballad of Wallis Island has been out for a few weeks, and I finally got to see it. I had heard some good things about it, so I went in with relatively high expectations, and somehow this film surpassed them. Sometimes, films are primarily about what happens. Sometimes films are about how you feel about what happens. Wallis Island is that rare film in which what happens is just as important as how you feel about it. Not only that, but you might even find yourself pleasantly surprised at how you feel about it.

I must say that I walked out of Wallis Island, not really disappointed with the ending, but disappointed that we didn’t get the performance that the story built toward. Then, on reflection, I realized that this film ended in the most satisfying way possible. The filmmakers brilliantly set up the archetypal elixir that folk singer Herb McGwyer (Tom Basden) wanted was to reunite and sing with his former collaborator and ex-wife Nell Mortimer (Carey Mulligan). They equally as brilliantly set up the archetypal elixir that he needed was to move on from that time of his life, realize that those days are over and never coming back, and embrace his new circumstances.

I often tell screenwriters when I’m writing coverage for their screenplays that characters are much more interesting when they have an outer goal and an inner need. That interest increases when the outer goal and inner need conflict with each other. Movies are more dramatic when the main character’s inner flaw prevents him from achieving his outer goal, and that is most effectively played out at the all-is-lost moment that transitions us from Act II to Act III. Herb’s desire to rekindle a romantic relationship and new creative partnership with Nell flies in the face of his need to find his own sound and move on from a failed relationship that has no hope of finding success.

Serving as the conduit for this doomed reunion is Charles Heath (Tim Key), a widowed lottery winner who bought a magnificent home with his late wife on a remote island. Now, he wants McGwyer and Mortimer to play a private concert for him because he and his wife were such big fans. In his own way, Charlie is also stuck in a similar conflict between inner need and outer goal. He, too, needs to move on from the memory of his dead wife, stop living in the past, and find someone else to love. Amanda (Sian Clifford), a single mother who owns the local grocery store, seems to be the perfect match for him, but his awkwardness and devotion to his late wife prevent him from finding happiness in the now.

The screenplay, brilliantly written by Basden and Key, gives us enough story to allow Herb and Charlie to find the space to grow. Herb’s growth is more noticeable only because he has further to go. He’s a talented man whose best days are seemingly behind him as he struggles to find a new voice and a new sound. The problem is that he hasn’t emotionally recovered from his broken relationship with Nell. His career is waning, but the opportunity to get paid by Charlie offers him a chance to make enough money to cover the expenses of his new album. His inner conflict comes to a head when Nell shows up because Charlie hopes to get them to perform together one more time. The only problem is that she shows up with her new husband, Michael (Akemnji Ndifornyen), and she has left the music business behind.

We spend the second act watching Herb and Nell struggle to rediscover their sound. As they do, they rediscover their personal chemistry, and there is the possibility (danger?) that they might fall back into it. As an audience, we’re rooting for it on the outside, but we know it can never work. The second act ends with Nell leaving the island, never to play the gig with Herb. It’s an emotionally devastating scene.

I wanted to see the gig. Even if Herb and Nell remain “friends,” I thought as I watched the movie that it was important to see the gig happen. So, when it didn’t, and Herb plays the gig solo, I was initially disappointed. I wanted to know what their sound sounded like when they were at their peak. But that was the point that Basden, Key, and director James Griffiths were making. They were no longer at their peak and never would be again. What we saw instead was Herb rediscovering his joy of playing and performing. He no longer needed the old sound. The new sound was the key to his happiness. This ending was infinitely more satisfying than it would have been if they had performed together.

Charlie’s growth is not as dramatic as Herb’s, but it’s just as emotional. We discover that Charlie is a widower and that he and his wife were huge fans of Herb and Nell. Like Herb, Charlie is living in the past. He’s trying to fulfill a promise for someone who can no longer appreciate it, while the opportunity is there for him to share his life with a new person who can appreciate him. He eventually realizes and attains a level of happiness that he would never have had without Herb.

This screenplay is about two people who need to change but don’t know it. One of them thinks he’s happy, and the other one knows he isn’t but believes he deserves the misery he’s living with. The story slowly, effectively, and emotionally brings about the changes in both of these characters as they organically overcome and resolve their internal conflicts in a dramatic and satisfying way.

If you are a screenwriter writing a screenplay relying on internal conflicts in characters to drive the story, The Ballad of Wallis Island is absolutely a film you should see. If you are a movie fan looking for an emotionally satisfying film that will put you through an emotionally satisfying journey, The Ballad of Wallis Island is absolutely a movie you should see.

The Amateur wanted so badly to be a Jason Bourne movie. Unfortunately, it missed the mark. It was an entertaining movie with nice performances from Rami Malek as Charlie Heller, a CIA decoder whose wife is killed in a terrorist attack, and Laurence Fishburne as the CIA trainer, Henderson, who must get Heller ready for the field if he is to get revenge on those who killed his wife. Rachel Brosnahan also gives a nice performance as Heller’s wife, Sarah, who is tragically killed in a terrorist attack gone wrong. Holt McCallany is solid as Director Moore, a rogue CIA director directing illegal black ops who wants Heller out of the picture. Finally, Julianne Nicholson balanced Moore as the Director of the CIA, whose idealistic idea of cleaning up the CIA is threatened by Moore’s rogue actions.

That should have created a deep story with a compelling narrative and a dramatic plot. Unfortunately, director James Hawes gave us a film that was wide but shallow. It never allowed us to properly engage emotionally with what was happening in the story. Screenwriters Ken Nolan and Gary Spinelli also seemed to struggle with the source material provided by Robert Littell’s novel. It’s unfortunate that the screenplay and the film didn’t turn out better because the screenplay had the ingredients for a solid dramatic structure.

This is an adaptation of a novel, and novels can be challenging to adapt to screenplay format. Getting everything from a novel into a two-hour movie is impossible, so important story points almost always must be omitted. While watching The Amateur, I could tell early on that key story elements were being glossed over or left out entirely. Screenwriters often have a choice when adapting a novel into a screenplay. They can attempt to get as much information into the script as possible without diving too deeply into it. Or they can turn the screenplay’s focus onto a few key elements of the story from the novel and explore them more deeply. Hawes, Nolan, and Spinelli chose the former. They gave us a screenplay that was wide but shallow. They wanted to give the audience as much from the novel as possible, so they did that without deeply exploring any one component.

That gave us a fun film, but not an emotional one. That wouldn’t matter if they didn’t give us scenes that were clearly intended to elicit emotional responses, only to fall flat because not enough work was done to get us emotionally involved. We can’t get emotionally involved when the story and characters are flat. There’s not enough for us to latch our emotions onto. Again, that’s fine if this film wanted to be Commando. It was clear, however, that it was striving for more than that.

This is an entertaining film. It’s a popcorn movie that will give you your money’s worth if you see a matinee screening of it. The action sequences and some of the VFX make it worth seeing on the big screen rather than waiting for it to make it to your favorite streaming service. However, for whatever reason, Hawes couldn’t give us the drama we needed for the film to go from good to great. That is where the lack of structure in the screenplay comes in. As I often tell screenwriters for whom I provide screenplay coverage, story structure isn’t an arbitrary idea that producers and studio executives need to understand screenwriting. Dramatic story structure is integral to building drama in a story. It marks the protagonist’s progress towards accomplishing his goal.

Heller has a clear goal in The Amateur. He wants to get revenge on the men who killed his wife. The inciting incident, or the Call to Adventure, happens when his wife is murdered during a terrorist attack in London. He works for the CIA, and he wants them to bring the perpetrators to justice. He does what he’s good at and breaks the codes that allow him to discover who they are. His call is Refused by Dir. Moore, who gives him a line about this being a part of a bigger conspiracy. From there, Heller provided evidence that Moore is engaging in illegal black ops and blackmails him into allowing him to train as a CIA agent. At that point, Heller Crosses the First Threshold from Act I to Act II when he begins training. The issue is that this doesn’t happen until we’re 40 minutes into the film. That takes too long, leading the first act to drag. That delays the drama that should be building in the second act, which makes it more difficult to engage the audience.

The second act begins with the archetypal Tests, Allies, and Enemies stage of The Hero’s Journey, with Henderson training Heller. This part of the story should have been dramatic, showing the challenges Heller faces in being a field agent. Hawes gave us this to a degree, but it is glossed over so quickly in the film that it might as well not have happened. We then learn that Moore and his team feel they cracked the code to prevent Heller’s evidence from going public and order Henderson to kill him. However, when Henderson gets to Heller’s room, he discovers he’s gone with multiple passports and plenty of cash to travel the world. Henderson then tells Moore that Heller took advantage of all the training he gave him. However, that line even falls flat because we didn’t see any of that training happen.

Most people will tell you that screenplays are written in a 3-act structure. As I have pointed out, the best screenplays are written in 4 Acts. The Amateur would have been a more compelling story with a 4-act structure. The first two acts could have been written as I showed above; however, with the first act ending by page 30, and more time focused on Heller’s training. This would have allowed Heller’s relationship with Henderson to develop more, and that development was needed. We needed that relationship to be more than it was in the film. Henderson is Heller’s archetypal mentor, and this script would have been a lot more emotionally engaging, and things in the final act would have made a lot more sense and been a lot more plausible if Henderson was more of an archetypal ally to Heller as well. `

The third act, or Act IIB if you prefer, should have shown Heller killing the villain’s henchmen. Act IIB does end with an all-is-lost moment, as Heller loses his longtime ally, Inquiline (Caitriona Balfe), who has been helping him find the killers, is killed. Again, because Hawes didn’t do the heavy lifting of showing that Heller couldn’t do what he needed to do without help, this moment falls flat. The final act is about him finding the person who pulled the trigger, the group’s leader, and coming up with a creative way of bringing him to justice. Without giving too much away, this is another key moment where the terrorists are connected with Moore, but it’s nothing more than a coincidence that they were responsible for killing his wife. This script would have been much more effective if it had shown that Moore was pulling the strings the whole time. That would have provided the depth to the story that we would have needed, but the director and screenwriters opted for wide and shallow rather than a narrower but deeper approach.

The other thing the script lacks is stakes. Heller’s wife is already dead. He has nothing else to lose if he fails, other than his life. That should be enough, but it isn’t because we don’t care about him. Another thing I tell aspiring screenwriters is to give us the stakes and raise those stakes whenever you can. Heller needed more than just revenge. He needed some personal growth or to save something or someone else. The filmmakers attempted to show him growing as a person and getting over some internal fear, but it’s never clear what that fear is.

Again, this is an entertaining movie. If you’re just looking for something to kill a couple of hours while you gobble down popcorn and soda, this movie is for you. What I find frustrating about it is that I can see that it could have been better, and I have opinions on how it could have been better. Unfortunately, the filmmakers had other motivations. They made the movie they wanted to make, but it didn’t accomplish what they wanted it to achieve.

“Know your audience” is an oft-repeated phrase in Hollywood. Most ideas target specific audiences, and some of those audiences are larger than others. Naturally, if you have an idea for a high-concept blockbuster, the audience is going to be huge. However, there is much value to be found in something that might be more niche. Screenwriters must also remember when shopping their screenplays that the audience they hope will eventually see this in the theater is not the only audience for them to satisfy. First, they must impress an audience of studio executives and producers.

Another phrase people often hear is, “throw enough shit against the wall and something will stick.” It is very tempting to apply that philosophy when it comes to shopping your screenplay. You see value in getting as many eyeballs as possible on your script to increase the odds that two of those eyeballs will be attached to a brain that will react favorably to your script. Unfortunately, it doesn’t always work that way.

Several years ago, I was a reader for Walden Media. They became very popular and successful in the first decade of this century primarily for producing The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, as well as the subsequent Narnia films that followed over the course of the next few years. However, they also did very well by producing family-friendly films based on YA novels, like Hoot, Nim’s Island, Because of Winn-Dixie, and many others. Walden was primarily interested in adapting novels into films, but they would consider screenplays that met certain criteria.

Writing coverage can vary slightly from one production company to another. However, the overall basics are the same. The companies want a logline; a brief paragraph on the overall plot and tone of the story; ratings on storyline, premise, dialogue, and character; if the script was a recommend, a consider, or a pass; a synopsis of the story, notes describing the reader’s thoughts and critique of the screenplay; and finally, screenplay’s commercial potential. To all of that, Walden required its readers to evaluate another component of the story: Learning Potential.

Walden wanted strong thematic components in their films that offered the potential for learning some kind of lesson. If a screenplay didn’t target a family audience or contain learning potential, Walden wasn’t interested in it. And yet, I had to read many scripts that didn’t meet either of those criteria. My comments often included notes that described the script as worth considering, but not the type of script that Walden produced. It was a waste of time and effort for this writer and his or her manager or agent to submit the script to Walden. We weren’t the audience, and our audience wasn’t their audience. Yes, I still got paid to read the script, but it was still frustrating for me to spend time reading and evaluating something that clearly wasn’t what my company was looking for. It also must have been frustrating for the writer to get their work passed on.

There was one time when I was reading for Walden when this was particularly painful for me. I was assigned a script to read, and I loved it. The style of the story was similar to movies like Clueless and Legally Blonde. It was a witty script with a ton of snark. The pacing was crisp, the dialogue biting, and overall, it was one of the most entertaining scripts I’ve ever read. It had several laugh-out-loud moments with characters who were likable and had tremendous character arcs. The story worked on multiple levels and had a ton of depth and drama. It also had a tight structure and biting dialogue that added to the protagonist’s wit, sarcasm, and cynicism. I could envision this screenplay as a film the entire time I was reading it, and I could totally picture Lindsay Lohan in the leading role.

While it was based on a Young Adult Fiction novel, this wasn’t family entertainment. It was probably closer to Mean Girls than it was to Freaky Friday. I gave it a CONSIDER, which I knew I shouldn’t have done. I knew the script, as good as it was, did not meet Walden’s criteria of strong thematic components leading to learning potential. This was simply a funny screenplay with some nice action sequences that had high entertainment value. But it wasn’t for families, and it didn’t have a lesson or a moral. I remember discussing it with the executive I worked with at Walden, and he asked me point blank, “Is this for us?” I could only sigh in disappointment and tell him, “I don’t think so.”

Either the writer or, more likely, the agent didn’t do their homework when submitting it. Walden was fresh off the success of the first Narnia movie at the time, so they were a hot commodity in town, and people were trying to take advantage of that momentum. They were sending Walden material even when they knew Walden was unlikely to bite on the off chance that they would. That is not a good marketing strategy for a studio that is well run and committed to its creative principles.

Whether you have an agent or not, it’s critical that you research the companies you’re sending your script to. This is especially important if you send it to a production company with a definitive niche. For example, let’s say you’ve written a script like Iron Claw or The Fighter about a guy who’s a wrestler or a boxer and struggling with his career and personal life. Don’t bother submitting that script to NEON Rated. They’ve been very successful as a production and distribution company with credits like Parasite, Anora, Anatomy of a Fall, and I, Tonya. Three of those films were nominated for Best Picture, and two of them won. Even if your script is tonally similar to those films, NEON won’t likely be interested in it unless your boxer or wrestler is a person of color or gay. But neither Iron Claw or The Fighter would have worked at NEON. They primarily focus on stories with strong female leads or on films about the BIPOC and LGBTQ+ community, and both of those films were led by white men.

You probably shouldn’t send it to Blumhouse either. They have done very well with films like Get Out, Paranormal Activity, and The Purge. They obviously focus on horror, so they would be a great option if you’ve written a supernatural thriller rather than a sports drama. Depending on how bold your creative choices are in your script, IFC might be an option. Their subject matter is more diverse, but their content is more auteur-driven.

Even A24 could present challenges. They’re currently one of the most, if not the most, successful indie production companies. They churn out a lot of interesting and critically acclaimed movies. They’re also comfortable in multiple genres and with various styles. That might seem like a green light to send them whatever you have. However, there is a commonality amongst many of their films. They’re all quirky in some way. They’re all strong thematically and have a lot of subtext. Their screenplays always have more going on under the surface than they appear to. Whether it’s the time-bending Everything Everywhere All at Once, the science fiction camp of Mickey 17, or the coming-of-age mother-daughter story of Lady Bird, A24 has an underlying signature style that your screenplay should possess if you want them to consider your work.

Selling a screenplay is, in many ways, more difficult than writing the screenplay. Marketing it to the right people can be frustrating, and the temptation to just blast it out into the world is very strong. At least initially, writers and their agents and managers should consider a targeted search for production companies that consistently work in the space in which the screenplay lives. It’s not a guarantee that you will find someone who is interested in it, but it actually increases your odds to target your search than to just flood the market. Not only should you look into production companies, but if you work with an agency, find out if they represent any actors who have worked on similar projects. Having an actor attached to your script always makes it more attractive to any production company, especially those who produce films similar to what you’re working on.

Overall, be patient. Rome wasn’t built in a day. It’s more difficult to sell a screenplay now than it ever has been. But it’s not impossible, especially if you do your research. It’s not glamorous, but attempting to get your script in front of as many people as possible is the wrong tack. Do the legwork and get your script in front of the right people.

“Have fun storming the castle!”

Screenplay by William Goldman

After seeing Snow White a couple of weeks ago, I’ve wanted to write about it for a while. Unfortunately, as often happens, life gets in the way. I wanted to write a blog begging the good people at Disney to stop this madness. Then today, we found out that Disney is “pausing” the live-action remake of Tangled. I find that particularly interesting since Snow White’s story was more like Tangled than the original Snow White. I tend to stay away from the Disney live-action remakes. Most of my professional experience is in animation, and I feel that the live-action remakes diminish the legacy of these animated classics, so I choose not to support them.

However, I saw Snow White because MacKenzie and I planned to discuss it in our podcast. I was also mildly interested because I saw that, even though the Rotten Tomatoes critics’ score was low, the audiences generally rated it a bit higher. So I went in with an open mind, but with low expectations.

The first thing I will say is that I have no political beef with this film. While I’m not a fan of what Rachel Zegler (Snow White) said about the original, it’s her opinion and she’s entitled to it. You don’t have to agree with it, but she has a right to feel about the original however she feels about it. While I wish Gal Gadot (The Stepmother) felt a bit differently about what’s happening in Gaza, I can’t blame her, as an Israeli citizen, for having the opinions that she has about what is happening in that part of the world. Perhaps the most interesting thing about Snow White is that it’s that rarest of movies that equally pisses off both the left and the right.

My main beef with this film is that it honestly didn’t even look like they were trying. It didn’t look like the actors were trying. It didn’t look like the screenwriters were trying. It didn’t look like the costume designers were trying. It didn’t look like the director was trying. It certainly didn’t look like the VFX team was trying.

A lot of ire has been directed at the film for using CG dwarfs instead of hiring little people as actors to play them. I get the decision to go with motion capture because it presents a greater opportunity for interesting looks, and it adds to the fantasy elements of the film. But the motion capture was among the worst I’ve seen in a long time. This was much closer to The Polar Express than to Avatar. Dopey was the worst of all. They tried to humanize him too much, which made him look creepy. Also, they make him talk at the end, which totally destroys the iconic nature of that character.

It is not hyperbole to say that the original Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs is probably one of the top-5 most important films of all time. It’s not one of Disney’s best, but it is great, and it showed that animation could work and be successful in feature-length films. Had it bombed at the theater, there might not ever have been another animated feature, and animation would have continued to be relegated to short and eventually television. Instead, it racked up $8 million at a time when a movie ticket cost a dime for kids and a quarter for adults. It remains in the top-10 box office rankings in terms of number of tickets sold. It cannot be understated how important the film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs is.

For that reason, it should have been left the hell alone. You’re not going to remake Casablanca, Citizen Kane, or The Godfather. So leave your stinking mitts off Snow White. This epidemic of subpar live-action remakes must stop. Thankfully, Disney might be getting the hint. Snow White appears to be a box office failure, to say the least. While I never wish for movies to fail because I know how hard they are to make, I am happy that the market is telling Disney to move on to other things. If the remakes of Lilo and Stitch or Moana do well, then the train could be restarted, but for now, it looks like the studio could start to look for content in other places.