“Know your audience” is an oft-repeated phrase in Hollywood. Most ideas target specific audiences, and some of those audiences are larger than others. Naturally, if you have an idea for a high-concept blockbuster, the audience is going to be huge. However, there is much value to be found in something that might be more niche. Screenwriters must also remember when shopping their screenplays that the audience they hope will eventually see this in the theater is not the only audience for them to satisfy. First, they must impress an audience of studio executives and producers.

Knowing the audience is critical to setting your script on the path to success.

Another phrase people often hear is, “throw enough shit against the wall and something will stick.” It is very tempting to apply that philosophy when it comes to shopping your screenplay. You see value in getting as many eyeballs as possible on your script to increase the odds that two of those eyeballs will be attached to a brain that will react favorably to your script. Unfortunately, it doesn’t always work that way.

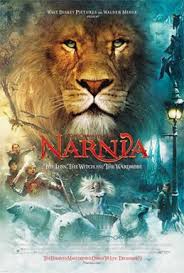

Several years ago, I was a reader for Walden Media. They became very popular and successful in the first decade of this century primarily for producing The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, as well as the subsequent Narnia films that followed over the course of the next few years. However, they also did very well by producing family-friendly films based on YA novels, like Hoot, Nim’s Island, Because of Winn-Dixie, and many others. Walden was primarily interested in adapting novels into films, but they would consider screenplays that met certain criteria.

Writing coverage can vary slightly from one production company to another. However, the overall basics are the same. The companies want a logline; a brief paragraph on the overall plot and tone of the story; ratings on storyline, premise, dialogue, and character; if the script was a recommend, a consider, or a pass; a synopsis of the story, notes describing the reader’s thoughts and critique of the screenplay; and finally, screenplay’s commercial potential. To all of that, Walden required its readers to evaluate another component of the story: Learning Potential.

Walden wanted strong thematic components in their films that offered the potential for learning some kind of lesson. If a screenplay didn’t target a family audience or contain learning potential, Walden wasn’t interested in it. And yet, I had to read many scripts that didn’t meet either of those criteria. My comments often included notes that described the script as worth considering, but not the type of script that Walden produced. It was a waste of time and effort for this writer and his or her manager or agent to submit the script to Walden. We weren’t the audience, and our audience wasn’t their audience. Yes, I still got paid to read the script, but it was still frustrating for me to spend time reading and evaluating something that clearly wasn’t what my company was looking for. It also must have been frustrating for the writer to get their work passed on.

There was one time when I was reading for Walden when this was particularly painful for me. I was assigned a script to read, and I loved it. The style of the story was similar to movies like Clueless and Legally Blonde. It was a witty script with a ton of snark. The pacing was crisp, the dialogue biting, and overall, it was one of the most entertaining scripts I’ve ever read. It had several laugh-out-loud moments with characters who were likable and had tremendous character arcs. The story worked on multiple levels and had a ton of depth and drama. It also had a tight structure and biting dialogue that added to the protagonist’s wit, sarcasm, and cynicism. I could envision this screenplay as a film the entire time I was reading it, and I could totally picture Lindsay Lohan in the leading role.

And we had to pass on it.

While it was based on a Young Adult Fiction novel, this wasn’t family entertainment. It was probably closer to Mean Girls than it was to Freaky Friday. I gave it a CONSIDER, which I knew I shouldn’t have done. I knew the script, as good as it was, did not meet Walden’s criteria of strong thematic components leading to learning potential. This was simply a funny screenplay with some nice action sequences that had high entertainment value. But it wasn’t for families, and it didn’t have a lesson or a moral. I remember discussing it with the executive I worked with at Walden, and he asked me point blank, “Is this for us?” I could only sigh in disappointment and tell him, “I don’t think so.”

Either the writer or, more likely, the agent didn’t do their homework when submitting it. Walden was fresh off the success of the first Narnia movie at the time, so they were a hot commodity in town, and people were trying to take advantage of that momentum. They were sending Walden material even when they knew Walden was unlikely to bite on the off chance that they would. That is not a good marketing strategy for a studio that is well run and committed to its creative principles.

Whether you have an agent or not, it’s critical that you research the companies you’re sending your script to. This is especially important if you send it to a production company with a definitive niche. For example, let’s say you’ve written a script like Iron Claw or The Fighter about a guy who’s a wrestler or a boxer and struggling with his career and personal life. Don’t bother submitting that script to NEON Rated. They’ve been very successful as a production and distribution company with credits like Parasite, Anora, Anatomy of a Fall, and I, Tonya. Three of those films were nominated for Best Picture, and two of them won. Even if your script is tonally similar to those films, NEON won’t likely be interested in it unless your boxer or wrestler is a person of color or gay. But neither Iron Claw or The Fighter would have worked at NEON. They primarily focus on stories with strong female leads or on films about the BIPOC and LGBTQ+ community, and both of those films were led by white men.

You probably shouldn’t send it to Blumhouse either. They have done very well with films like Get Out, Paranormal Activity, and The Purge. They obviously focus on horror, so they would be a great option if you’ve written a supernatural thriller rather than a sports drama. Depending on how bold your creative choices are in your script, IFC might be an option. Their subject matter is more diverse, but their content is more auteur-driven.

Even A24 could present challenges. They’re currently one of the most, if not the most, successful indie production companies. They churn out a lot of interesting and critically acclaimed movies. They’re also comfortable in multiple genres and with various styles. That might seem like a green light to send them whatever you have. However, there is a commonality amongst many of their films. They’re all quirky in some way. They’re all strong thematically and have a lot of subtext. Their screenplays always have more going on under the surface than they appear to. Whether it’s the time-bending Everything Everywhere All at Once, the science fiction camp of Mickey 17, or the coming-of-age mother-daughter story of Lady Bird, A24 has an underlying signature style that your screenplay should possess if you want them to consider your work.

Selling a screenplay is, in many ways, more difficult than writing the screenplay. Marketing it to the right people can be frustrating, and the temptation to just blast it out into the world is very strong. At least initially, writers and their agents and managers should consider a targeted search for production companies that consistently work in the space in which the screenplay lives. It’s not a guarantee that you will find someone who is interested in it, but it actually increases your odds to target your search than to just flood the market. Not only should you look into production companies, but if you work with an agency, find out if they represent any actors who have worked on similar projects. Having an actor attached to your script always makes it more attractive to any production company, especially those who produce films similar to what you’re working on.

Overall, be patient. Rome wasn’t built in a day. It’s more difficult to sell a screenplay now than it ever has been. But it’s not impossible, especially if you do your research. It’s not glamorous, but attempting to get your script in front of as many people as possible is the wrong tack. Do the legwork and get your script in front of the right people.