“Do you guys wanna go see a dead body?”

Screenplay by Raynold Gideon & Bruce A. Evans

“Do you guys wanna go see a dead body?”

Screenplay by Raynold Gideon & Bruce A. Evans

We all know how challenging the year 2023 was in the entertainment industry. We don’t need to rehash the double strikes, the layoffs, the mass exodus out of town, or the lives and careers that were either stalled or completely snuffed out. As challenging as the spring and summer were, optimism abounded in the autumn as both strikes ended within weeks of each other, and thousands of people were poised and ready to return to work.

But that isn’t what happened.

Very few people actually returned to work, and the winter brought with it the coldness of uncertainty. When would projects start gearing up again? When would the entertainment business go back to being in business? Well, with two more strikes looming in 2024, the answer is, who knows? One would think that the studios would be smart and use the experience of last year to their advantage. One would think that they would want to be proactive and get through negotiations with IATSE and the Teamsters now so that there won’t be two more strikes this year. Instead, for reasons unknown, the corporations that run the studios seem content to sit on their money and play the waiting game… again.

Corporations have owned movie studios for a long time. Once the studio system was scuttled in the 1960s, large corporations added movie and television studios to their various portfolios, but left people in charge of those entities through the 70s, 80s, and 90s who knew what they were doing and were passionate about movie making and storytelling.

We obviously live in a different world than we did thirty, forty, and fifty years ago, but the paradigm shift that has occurred in Hollywood threatens its very existence. Hollywood has often been a risk-averse place. Executives want to cast stars they know will draw audiences to star in movies they think people want to see. There was a time when movie moguls made those decisions, but now they’re being made in board rooms.

That’s not to say that men like Walt Disney, Jack Warner, Louis B. Mayer, and the rest of the movie moguls of Hollywood’s Golden Age were infallible. Walt Disney fired animators who went on strike and only hired them back when ordered to by the courts. He then made many of their lives so miserable at the studio that they ended up quitting anyway. Jack Warner ruled his studio with an iron fist, holding actors to iron-clad contracts and refusing to let them out of them, and he ended up screwing over his own brother to gain complete control of the studio. Louis B. Mayer’s temper was legendary, and he liked to meddle in the lives of his actors.

Clearly, these men weren’t saints. But they were movie men. They loved making movies they were creative people by nature. They knew what their audiences wanted, and they knew how to deliver that. Not every movie was a blockbuster, but their studios were, for the most part, profitable and very often prosperous. Also, the movie studios these men ran were their entire business. They weren’t pieces of multinational, multi-billion-dollar entities. Disney, Warner, Mayer, and others were the heads of companies, not corporations. These companies produced movies and, eventually, television, but not much else.

Today, The Walt Disney Company owns multiple studios and properties. Warner Bros. has been bought and sold so many times it’s impossible to keep track. Paramount, once the largest studio in town, is owned by Viacom. The MGM lot is now Sony. Comcast owns Universal. The movie studios now are but smaller pieces of the giant portfolios that these corporations oversee. That is likely why there is no urgency for them to negotiate with IATSE and the Teamsters. Still, they don’t want to throw a bunch of money at a project that has a 12-week schedule only to have to shutter it after 10 weeks when IATSE and/or the Teamsters go on strike for God knows how long.

At the beginning of the writers’ strike, the studios allowed the thoughts of one executive to leak when the strategy of letting writers lose their homes and then having them crawl back to the table for better studio terms became public. When people realized some of those homes would also be the domiciles of wives and children, the “let them eat cake,” mustache-twisting villains we all thought the studios were became a reality.

If these executives care about movies, it’s only so they can say that they’re rubbing elbows with the stars and get to go to all the awards shows in February and March, along with the red carpet premiers at the Chinese Theater or wherever else they happen to be. Otherwise, movies are being made by boardroom decisions. That’s the only explanation for what the movie business has become over the past decade and a half.

I think there is. The cynic in me says that these executives are so blind that they will continue to do what they’ve been doing. The idealist in me says that they must see the change that needs to be made. The Marvel and DC universes are dying. But movie franchises like Avatar and Dune have shown that they can be successful when a single director is allowed to express his vision without too much meddling from a studio. Movies like Anyone But You showed that audiences will go see smaller movies. Perhaps not in droves like the big tentpole franchises, but that movie was profitable. You can say what you want about how good it was, or it wasn’t, but it made over $80 million on a $20 million budget. Someone in the accounting office must notice that.

When Cord Jefferson gave his acceptance speech at the Academy Awards for winning the Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay for American Fiction, a film that made over $20 million on a budget of under $10 million, he implored Hollywood to change its business model. “Instead of making one $200 million dollar movie,” he said, “make ten $20 million dollar movies.”

Will they take his advice? Only time will tell. Partly, it’s up to audiences to speak up with their wallets because, ultimately, it’s the money that listens. If another $20 million-dollar RomCom comes out in the next couple of months, and it makes another $80 million or $100 million, they’ll have to take notice. Someone has to convince the members of the boardroom that not every movie has to be a blockbuster. Having a profitable business that employs a lot of people, provides entertainment to millions of others, and brings more eyes to their other brands can be just as valuable.

“Algebra is like sheet music. The important thing isn’t can you read music, it’s can you hear it. Can you hear the music, Robert?”

Screenplay by Christopher Nolan

In what was one of the more anticlimactic Oscar nights in recent memory, Oppenheimer surprised absolutely no one by taking home the Academy’s most prestigious award, along with six others to cap off what was a dominant awards season. The Christopher Nolan blockbuster also took home the awards for Best Director (Nolan), Best Actor (Cillian Murphy), and Best Supporting Actor (Robert Downey, Jr.), making it the first film since Ben-Hur (1959) and only the fourth film over all (Going My Way from 1944 & The Best Years of Our Lives from 1946) to win all four of those awards.

Concluding one of the most tumultuous and torturous years of in the history of Hollywood, a year that was marred by two major strikes that threatened to derail the entire industry, Oppenheimer was one of the films that saved the summer season, Barbie being the other, and both of the Barbenheimer movies were rewarded by receiving multiple Oscar nominations, including both getting nominations for Best Picture. And while Barbie dominated the box office, pulling in nearly $1.5 billion compared to almost $960 million for Oppenheimer, the latter dominated awards season from the Golden Globes through the Oscars.

What was it about Oppenheimer that made it such a runaway winner in a year that (IMHO) should have been wide open? The last time a “science” movie like this won was A Beautiful Mind in 2001. But it didn’t have the traditional underdog thematic components of that film. It was also the first true blockbuster to win since The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King in 2003, and it was the first Best Picture winner to surpass $100 million at the box office since 2012’s Argo. But as mentioned. Barbie outdid Oppenheimer at the box office by more than half a billion dollars.

To be perfectly honest, I have no idea why Oppenheimer struck the chord that it did. It was an excellent film, but there were several films that were nominated that I liked better. It had high entertainment value, but I thought there were other films that were more entertaining. It had a very good screenplay, but there were several movies with screenplays that were at least as good. The production design was outstanding, as were the lighting, editing, and cinematography, but there was very little in Oppenheimer that was groundbreaking despite its Oscar wins for cinematography and editing. Again, I thought there were films this year that outdid Oppenheimer in all of those categories.

Ultimately, what likely got Oppenheimer the win, in my opinion, was the totality of the production. Early in the Academy’s history, the Best Picture category was called “Best Production.” If one was to look at the award in that context, Oppenheimer was clearly the best production. It was the film that took all of the elements of filmmaking, from direction to screenwriting, to editing, and all of the stages in between, and in its totality, was the strongest production.

This was an exceptionally made film that also had a compelling story and characters that the audience could engage with, whether they were rooting for them or against them. Nolan, who also penned the Oscar-nominated screenplay, did an outstanding job of weaving the complexity of who Oppenheimer, the man, was. Nolan also effectively showed all of the people who were trying to destroy him, and how he really was a modern-day Prometheus in ways both literal and figurative. He provided the human race with a new kind of fire, and both he and the human race will be punished for it forever.

All of the acting in this film was also superb. Murphy and Downey, Jr. won Oscars in their respective categories and Emily Blunt was also nominated for Best Supporting Actress. She didn’t win, but her performance was gritty and hard-edged as Oppenheimer’s alcoholic wife, Kitty, who was the only one who tried to make him stand up for himself when the entire weight of the United States government was trying to destroy him for being a communist. Kitty may have had the most depth of any character. She broke up his initial marriage by getting pregnant by him, then didn’t want to take care of the baby. She struggled with alcohol and was not a very good mother to their children. However, her loyalty to Oppenheimer was unflappable and she stood by him to the end.

I think the reason this film didn’t quite hit the mark for me as far as being the best movie of the year was the emotional component or at least the lack thereof. Christopher Nolan is a clinical filmmaker. I wouldn’t say his films are devoid of emotion. Certainly, there have been deeply emotional moments across many of his films. But that’s just it. They’re moments. Just as there are emotional moments in Oppenheimer, it is not an emotional film. I didn’t get the emotional punch from Oppenheimer that I did with some of the other films from 2023. While the characters were engaging, most of the relationships were not. While Oppenheimer was a technically proficient film, it was not an emotional one. I liked it, but I didn’t care about what happened as much as I did in the other nominees.

Did the Academy get it right?

This was a very interesting year. I actually liked all of the films nominated for Best Picture, and that is a rarity, especially since the Academy increased the number of nominees to ten. I honestly wouldn’t have been disappointed with any of this year’s nominees winning. That said, I would not have voted for Oppenheimer. My favorite film of the year was The Holdovers for the reasons I mentioned above about the emotional component. I was far more engaged in The Holdovers and I cared immensely about the characters and what they were going through and I found the film to be much more satisfying. I also liked Maestro, American Fiction, Barbie, Anatomy of a Fall, Poor Things, Killers of the Flower Moon, and Past Lives better than Oppenheimer. That’s no shade towards Oppenheimer. I liked it a lot. You could even say that I loved it. What it does say is that 2023 was a very competitive year and ten outstanding films were nominated for Best Picture. I feel like if any of these films were made in the last three years, they would have been the favorite over almost anything that was nominated in any of those years. So while Oppenheimer wasn’t the film I would have voted for, I would still say that the Academy did not get it wrong, even if I’m unwilling to say that they got it right.

Should you see it?

Yes you should. If you’re interested in quality filmmaking, excellent screenwriting, terrific acting, and compelling storytelling, then this is a film you should actually see. I don’t know how historically accurate it is, but it certainly humanizes one of history’s most complex and complicated personalities, and certainly one the most important people of the twentieth century, if not all time. I don’t think it’s hyperbole to say that. This is a film fan’s film, and if you haven’t seen it already, it’s worth the three hours you’ll spend watching it.

“You want to talk to God? Let’s go see Him together. I’ve got nothing better to do.”

Screenplay by Lawrence Kasdan

After finally getting to see American Fiction, it is clear to me why it was nominated for Best Picture. I don’t know if it will win, and I don’t even think it’s my favorite movie of the year. It isn’t the only movie with a powerful message, and American Beauty is more on the nose with its messaging than some of the other Oscar nominated films are this year. That said, American Fiction is a powerful film with powerhouse performances by the actors and a script that is sneaky-good.

The screenplay, which was nominated for Best Adapted Screenplay at this year’s Oscars, is a great mix of thematic storytelling and powerful dialogue. There are a lot of very uncomfortable ideas being discussed in this film in ways that shouldn’t make us laugh but do. There were scenes when I was laughing uproariously at things that shouldn’t have been funny but were incredibly funny within the context of what this script was saying. Through the screenplay, American Fiction challenges the viewer, whether that viewer be African American, Caucasian, or any other race or ethnicity, to examine how they examine race. But that’s not all the film does. This is a deep and complex film that also tackles issues of family relationships, romantic relationships, and professional relationships and how each of those relationships requires us to wear a different mask for those occasions.

In my opinion, the most important component of this screenplay is the dialogue. The most prominent message this film delivers is that what we say is less important than how we say it. Writer/Director Cord Jefferson effectively showed us a writer in Thelonius “Monk” Ellison (Jeffrey Wright), who is an abrasive, if good-natured person of color who is trying to articulate complex subject matter in an educated way but is being undermined by Sintara Golden (Issa Rae), who is also highly educated but is writing her novels using much more urban language that is commonly associated with African-American culture. Frustrated with the hypocrisy of the soft racism of low expectation, Monk writes a book as a joke under a pen name that uses all of the urbane syntax, and suddenly people are interested. Needing the money to take care of his mother, who is suffering from early-onset Alzheimer’s, Monk reluctantly agrees to have the book published, and he sells the movie rights. Both the publisher and the producer are white, and neither of them has a clue about what’s going on. Then, the longer the charade persists, the more Monk loses control over who he believes he is, and that causes him to lose control over his own life.

American Fiction is a smart film that forces us to examine what it means to be tolerant and how well-intentioned people can still get it massively wrong. Another nice thing about it is that it doesn’t pretend to tell us how to get it right. We still need to figure that out for ourselves.

“You know something, Utivitch? I think this just might be my masterpiece.”

Screenplay by Quentin Tarantino

It pains me to say this. It really does. I have been a Disney fan since I was a kid, and I even worked there for a few years around the turn of the millennium. I raised my daughters watching Disney movies, and there was a time in my life when Disney could do no wrong in my mind. Those days are gone now, and this movie is easily a bottom-5 Disney Animated Feature. I can usually find at least a few redeeming things about almost any Disney film, but this one left me completely flummoxed. The film made no sense from a story perspective, from a character perspective, or even from a design perspective.

I worked at Disney during a pretty dark time. The wave that produced blockbusters like The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, The Lion King, Mulan, and Tarzan had crested. The Florida studio would produce Lilo and Stitch during that period, but the Burbank studio was struggling, and the company went through a very clumsy transition from traditional hand-drawn animation to a CGI pipeline. What was worse, though, was that the studio had lost its way in terms of crafting wonderful stories that were populated by intriguing characters. The studio was trying to make movies that would appeal to everyone rather than just making good movies and letting the rest take care of itself. I fear that Disney is in a similar situation today.

The wave that produced Tangled, Frozen, Moana, and Encanto has crested, and the most recent efforts, Strange World and Wish, are films with stories that are thin and characters we don’t care about. What’s worse is that you could always at least count on Disney films to look good, but the visual styles of these films, and of Wish in particular, felt confused and disorganized.

From a storytelling standpoint, but script just didn’t work on any level. First of all, the concept just didn’t make sense, there was never a clear idea of what this story was about. Since there was no clarity in what the story was about, the characters weren’t developed enough to have clear goals. Without those goals, it was impossible for the story to have a tight dramatic structure. That is screenwriting 101, and this movie failed. Screenwriters Jennifer Lee and Allison Moore just did not do enough to build this script from the inside out, and without that foundation, the story fell flat.

The characters had no depth.

Asha (voiced by Ariana DeBose), the main character had a relatively ambiguous goal. According to the concept of the story, King Magnifico (Chris Pine) created this utopian society where people could come and live in peace. They would express their wildest wish to him, which he would magically keep, causing them to forget what it was, and once a year, he would grant someone their wish. Asha wanted her grandfather to get his wish since he was going to turn 100, and from there, the story completely fell apart.

But the main issue with Asha is that she has no depth. The best characters always have an inner weakness or flaw that they need to overcome, and Asha doesn’t have anything that I could see no flaw in her personality. She was totally likable and a little quirky, but she didn’t have any character trait that could accurately be described as a flaw. The problem with that is that the transition between Act II and Act III is often a moment when the hero seems to lose everything, often due to the fact that they haven’t overcome that flaw or weakness. It’s usually the most dramatic moment in the script and sets the Hero forward to finally claim the prize in Act III. That moment completely fell flat in Wish because there was no flaw to cause Asha to seem to fail or for her to overcome. That left us with an undramatic story and an anticlimactic finish to the story.

There was also no clear motivation from Magnifico. Why did he want other people’s wishes in the beginning? Why was it important that they forget what the wishes were once they gave them to him? What was he getting out of any of this?

This might have been the most upsetting thing about Wish. While the movie was beautiful, there was no direction to the production design. The studio seemed to be influenced by previous success from other studios that added unique elements to their looks, like Into the Spiderverse from Sony and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles from Paramount, but those studios clearly identified the motivation behind the interesting looks that they had. There was none of that in Wish, and it seemed like they were playing with the different looks in the movie with no real idea as to why.

Overall, this was a pretty lackluster effort from the studio that should be leading the charge in animated features. I will always be a fan of Disney films, and that’s why it’s so disappointing when they come up so short when we all know what they’re capable of at their best. At their best, there is no one better than Disney. Unfortunately, this film is far from their best, and I don’t think Wish could be included in the top-5 animated films released this year.

Do better, Disney.

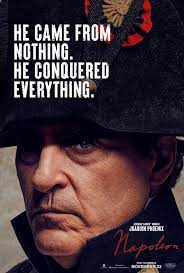

I had been looking forward to Napoleon’s release for months. I don’t remember when I saw the first trailer for it, but as soon as I saw that Ridley Scott was directing Joaquin Phoenix, my initial response was, “Yes, please!” I had visions of Gladiator dancing in my head, and my expectations for this film were through the roof. And I will freely admit, that’s on me. I don’t know if my expectations for this film were unreasonably high, but they were high, and Ridley Scott and Napoleon did not meet them.

Napoleon is a superb visual film. The production design is gorgeous, the costumes were immaculate, the VFX enhanced everything without drawing attention away from the narrative, and the lighting reflected the mood of every scene perfectly. Ridley Scott and his team built a world that felt lived in. There were times when the costumes were ill-fitting, which brought a subtle realistic component to the look of the film. There were several scenes that took place at night, and candlelight provided the only illumination, which brought warmth to those scenes and often matched the warm mood those scenes were trying to convey. The battle scenes were often gray, wintery scenes, with the only color being the red blood that freely splashed through the air and on the ground. The production design was beautiful when it wanted to be and jarring when it had to be.

The cinematography was amazing. Director of Photography Dariusz Wolski presented a world that felt like eighteenth and nineteenth-century Europe. He wasn’t afraid to make us wait with long takes that slowly revealed what we needed to see. In equal parts, he showed us what was gruesome and what was glamorous about the day.

One of the projects that Stanley Kubrick wanted to make but was unable to before his death was a film about Napoleon and Josephine. I’m sure Ridley Scott was aware of that, and there are a lot of moments that seem to pay homage to Kubrick as a filmmaker, whether in the use of Kubrickian cinematography tropes, or the use of classical music as the score in ways that felt like Kubrick was in the editing room, there were stretches of this film that felt like they were being directed by Kubrick himself.

Vanessa Kirby as Josephine was a treasure. She played the role with panache and wit and snark and pain. All of the levels were perfect, and she brought Josephine back to life in a way that made it plausible that the most powerful man in the world at that time obviously would have been obsessed with her. Kirby’s performance as Josephine was nothing short of sublime.

Overall, this is a very entertaining film. The action sequences are exciting and riveting, and the movie, as a whole, did what it needed to do to keep the audience engaged, at least on the surface level.

From a storytelling standpoint, this film is full of missed opportunities. As engaging as Napoleon was on the surface, it lacked that much in-depth. It felt like Ridley Scott was trying so hard to cram as much as he could into two and a half hours, and in doing that, he didn’t adequately explore anything in terms of how these characters, especially Napoleon and Josephine, felt about each other. That led me to walk out of the theater realizing that I didn’t care about any of them. There were moments in the film that should have been emotionally powerful but fell flat because the groundwork hadn’t been laid to create depth in their relationships.

I remember seeing a quote from Kubrick when discussing why he wanted to make a film about Napoleon and Josephine, and he relayed that he was fascinated by the intensity and passion in their relationship. Ridley Scott teased us in this film with one scene of Napoleon telling Josephine that she was nothing without him, and then her turning the tables to get him to admit that he was nothing without her. It showed at once the potential for toxicity and codependency that could have driven the emotional content of the story, and then he never went back to it. Other than giving us some narration of letters they wrote back and forth, there was nothing that built their relationship.

In fact, just the opposite happened when there were sex scenes that showed Josephine completely disinterested and Napoleon only interested in providing an heir for himself. We saw no passion and even less emotion. Then, at the critical time when Napoleon discovers that Josephine has died, the audience should have been given an emotionally impactful scene, but it fell flat. Then, at the end of the film when we learn that Napoleon’s last word was “Josephine,” we don’t care. We weren’t adequately shown the love they had for each other, and other than one scene where Napoleon pulls Josephine under the breakfast table to make love to her, we weren’t shown the passion that they had for each other. All of that was crucial in giving the audience an emotional hook upon which to hang their hats, and we never got it.

Vanessa Kirby’s performance as Josephine may have been sublime, but she was miscast. Joaquin Phoenix’s performance as Napoleon was understated and brooding in its intensity, but he was miscast as well. In real life, Josephine was ten years older than Napoleon, and that was the reason that she was unable to become pregnant and produce him an heir. That age difference was at least reversed in this film, and it created a disconnect. Josephine already had two children from her deceased husband when she met Napoleon, and if you didn’t know about their real-life age difference, the fact that she was unable to get pregnant in this film wouldn’t make sense. It also snubs much of the realism that the filmmakers were striving for in other areas. The decision is understandable from a marketing perspective, but it created a disconnect in the film that, artistically, they weren’t able to overcome.

Overall, I give this film a C. Perhaps that’s due to my overinflated expectations for the film, but I feel like that’s being generous. I was entertained, but being entertained by a film like this isn’t enough. I wanted to feel something and I felt nothing. Walking out of a movie like this feeling empty is worse than feeling bad. I wanted a lump in my throat at the end of this film but was left feeling hollow. Still, I would recommend seeing it in the theater if you get a chance. The visuals and battle scenes are worth it.

The Holdovers was a little bit Dead Poets Society, a little bit Scent of a Woman, and a whole lot of charming and entertaining. This film was a lot of fun, and it was very much a character-driven film. That is to say that there wasn’t a ton of plot and there was even less action. This was a story about characters who were broken and either didn’t know how to heal or didn’t even know that they needed to heal. Circumstances brought them together and forced them to be together for the Holidays, and they all slowly came to grips with where the pain was coming from in their lives and how they could manage it.

The main character in this story is Paul Hunham (Paul Giamatti), a history teacher at a prestigious New England prep school for boys whose crankiness is matched only by his pretentiousness. He seems to relish in giving the boys grades that will prevent them from getting into the Ivy League school of their parents’ choice and he revels in putting these spoiled and entitled brats in what he thinks is their place. We learn later that this misplaced populism isn’t in him from principle so much as it has been ingrained in him by events from his past that have shaped who he has become, and he has never addressed those issues to this point in his life. The two and a half weeks he spends held over in the school over the Holidays will force him to confront that past and will force him to grow as a person and a human being. The character arc that Paul experiences is both satisfying and heartwarming as he goes from tyrant to prince, and it happens completely organically within the confines of the story.

Angus Tully (Dominic Sessa) is the unfortunate student who has to stay over the Holidays with Mr. Hunham. Left behind when his mother and stepfather went to St. Kitts and then were unavailable to give permission for him to go with other kids on a skiing trip, Angus must endure 3 weeks alone with Mr. Hunham, the least favorite teacher of everyone in the school. Angus’s scars are more visible than Hunham’s, but Angus tries to mask them with a tough attitude and a cocky disposition. Angus is another character with a terrific character arc, as he goes from a petulant malcontent to a sensitive kid who seems to have found is place in the world and is comfortable with it.

The third character in our triumvirate was Mary Lamb (Da’Vine Joy Randolph) head of the cafeteria and the mother of a former student of the school who was recently killed in Vietnam. She puts on a brave face for most of the film, but she is being torn apart on the inside by the memory of her son and she misses having him in her life. He was able to attend the school because she worked there, but going to an Ivy League school was beyond her means so he joined the army thinking he could go to college on the GI Bill once he got out. Randolph’s performance in this film is beautifully tragic, as she loses just enough control of her emotions just enough times for us to be able to understand the pain she trying to squelch. Her arc is different from Angus’s and Mr. Hunham’s but they’re all connected to each other and she would not have been able to go on her journey without them.

The plot of the story is really secondary to the character’s journeys and it essentially serves as a vehicle to facilitate the journeys the characters experience. The argument could be made that the movie is a bit episodic, except that the various scenes do build off each other and there are a lot of things that are planted early in the screenplay that are paid off later. All of the scenes demonstrate the growth of the characters and they all fit seamlessly together. Most episodic films could have the various scenes interchanged and nothing would change in the overall story. That is not the case with The Holdovers and screenwriter David Hemingson did an outstanding job of meticulously crafting a narrative that didn’t overpower the character growth but demonstrated perfectly how these broken people fixed each other.

Overall, this is a feel-good film that is very entertaining and should deservedly see its fair share of recognition come Awards Season.