“He’s a common, ignorant slob. He don’t even speak good English.”

Screenplay by Reginald Rose

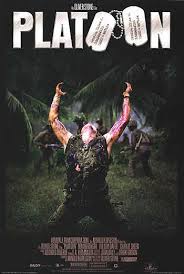

If 1984’s Amadeus was the best film of the 80’s, then 1986’s Platoon was certainly the most intense. I would seriously have to consider ranking Platoon as the #2 film of the decade, or at worst the #3 film behind Amadeus and Raging Bull. Platoon is a powerful film that demands to be noticed, but is so expertly crafted that it’s easy to forget how well-made a film it is due to the hype and notoriety that surrounds it and it’s writer/director Oliver Stone.

If 1984’s Amadeus was the best film of the 80’s, then 1986’s Platoon was certainly the most intense. I would seriously have to consider ranking Platoon as the #2 film of the decade, or at worst the #3 film behind Amadeus and Raging Bull. Platoon is a powerful film that demands to be noticed, but is so expertly crafted that it’s easy to forget how well-made a film it is due to the hype and notoriety that surrounds it and it’s writer/director Oliver Stone.

Oliver Stone was already a known commodity in Hollywood by the mid-80’s having written the screenplays for such successful films as Midnight Express, Conan the Barbarian and Scarface. He had already directed a couple of features as well, but Platoon, a film based on Stone’s own experiences as a soldier in Vietnam, launched him immediately to the top of Hollywood’s upper echelon of film makers and he would also spend the next decade and a half as one of the more polarizing figures in the entertainment industry. Stone was a film maker who had a definite political point of view, and his films that would follow Platoon, most notably, Wall Street, Born on the Fourth of July, JFK, Natural Born Killers, and Nixon demonstrated that he had a progressive, if not slightly paranoid vision of our society and the world in general. That he was so comfortable and confident in putting out what, at the time, were somewhat controversial points of view, helped to make Stone such a polarizing figure. With all of that being said, and his politics notwithstanding, Oliver Stone is an exceptional film maker and Platoon demonstrated his skills very effectively.

I would also like to point out that Stone at least deconstructed his own paranoid image with a cameo in the film Dave where he’s being interviewed by Larry King and he’s the only one who suspects that a conspiracy is afoot and that Dave is not the real president. Here is a link to that clip.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zHgyUL3M4IY

Let’s get back to Platoon. This is an extraordinary film on several levels, as it has incredible characters, a compelling story and was shot in such a way as to heighten the drama and the tension to nearly unbearable levels. I was actually discussing with a friend of mine how expertly Stone was able to create scenarios in which nothing seemed to be happening and yet the tension would ratchet up with each cut and with each passing moment. There is a scene where they are out on patrol and they come across a network of bunkers. By this time we’ve met everyone in the platoon and we feel like we know each of them pretty well (more on that in a bit). A couple of the men search inside the bunkers, while others look around the outside and others still patrol the perimeter. There’s a little bit of dialogue and no music. The only sound is the ambient sound from the environment and the sparse dialogue the characters speak. But the tension is palpable. Stone does an amazing job of setting up the scene so that it’s possible the North Vietnamese troops could be close by. As the main character, Chris (Charlie Sheen) patrols ahead with Manny, we are just waiting for something bad to happen. This goes on for what seems like an eternity. For several minutes we watch knowing that the longer they stay in this position, the more likely it is that something bad is going to happen to them.

Sure enough, something bad does happen, but not what we’re expecting, which makes the scene so effective. The two troops looking through maps and other articles left behind had initially been very careful to look for booby traps. Finding none, they continue their search. Thinking they’ve found a trove of maps and other valuable information, one of them picks up the box and it explodes, blowing off both of his arms. Still no music, and only ambient sound and the acting of the character as he numbly stumbles out, falls and dies. Chris comes back to the platoon, but no one can find Manny. Eventually they do find him, and he’s been killed by the VC and strung up on a pole. This causes much anger among the surviving members of the platoon, especially Sgt. Barnes (Tom Berenger), who takes his frustrations out on the local residents of a village they’ve been dispatched to in order to find weapons and Vietcong sympathizers. While interrogating the village elder, he shoots the elder’s wife for no other reason than she was an annoyance and then threatens to kill the man’s daughter if he doesn’t talk.

This is where the film starts to make the viewer angry, and is another example of how Stone is such an effective film maker. He elicits emotions out of the audience, and not all of those emotions are comfortable. The scene in the village is a perfect example of that. In this scene we have American soldiers, the same soldiers that we were so concerned about just moments before, and they’re terribly mistreating these villagers. It’s a high-tension scene and characters that we’ve generally liked and rooted for are acting in a way that we’re ashamed of. You almost want to shout at the screen for them to stop and to get a hold of themselves and stop acting like animals. Finally Sgt. Elias (Willem Dafoe) shows up to bring some sort of sanity back to the situation. Then, after acting like a deranged lunatic himself for a moment, comes to his senses and stops some of the other platoon members from raping a couple of the young girls from the village. That bit of sanity in a completely insane moment allows us to empathize with Chris and with Elias and shows us that these are clearly the men we’re going to be rooting for over the rest of the film.

That leads me to the characters. Stone did a great job of introducing us to the characters in the platoon and the different factions within it, led by the respective sergeants. Sgt. Elias leads the side of the platoon who are more light-hearted and rebellious. They smoke weed and listen to psychedelic music when they’re on leave and take a more nuanced look at life. They also are primarily African Americans and Hispanics. The other side of the platoon is led by Sgt. Barnes, and they’re mostly white, primarily Southern and are heavy drinkers of beer and Jack Daniels. They don’t smoke weed and there is an arrogance about them that can certainly help them survive but also gives them a moral relativism that allows them to commit atrocities that you wouldn’t imagine doing under normal circumstances. The one thing they all have in common is that they’re all poor or come from poor backgrounds, other than Chris, who dropped out of college to volunteer for the army because he didn’t think that it was right that only the poor and disadvantaged were being sent off to fight.

We’re initially introduced to the platoon when Chris is sent out on his first ambush with them, and none of them come across as sympathetic to him or to us. Chris is being initiated right away into this special world and if he can’t handle the initiation he has no chance to survive. A little later on, Chris befriends King, who introduces him to the members of Elias’ faction, and he fits right in with them. After being introduced to Elias team and their pot smoking and rick music, we are introduced to Barnes’ team and their heavy drinking, their country music and more by-the-book military style.

One thing that I found very interesting, and Chris mentions this in his narration when he says, “we were fighting ourselves”, is that this division amongst the members of the platoon is symbolic of the divisions the nation was experiencing at the time. It reminded me a little of a scene from Titanic, which we’ll get to in a couple of months, where we see the people in steerage who dance and sing and live life to its fullest even through they’re poor juxtaposed to the upper class who sit quietly and dignified while the smoke their cigars and discuss world events in a setting that couldn’t be more boring. The differences in Platoon aren’t as stark, but are still there and still noticeable. It sets the stage for the inevitable conflict to come, and helps build the drama of the story.

One of the reasons I tend to prefer Amadeus to Platoon is that the former has a lot more subtext. It’s a much more thoughtful film that uses more film making motifs to create a more complete experience. Platoon, while not necessarily on the nose, is much more straight forward. While Amadeus is a thinking person’s film, Platoon does make you think, but in a different way. Platoon forces you to confront our nation and our way of life in a manner that makes you question its supposed superiority. Platoon forces you to ask if we really are the great nation that we’ve always been told we are, and it does it in a straight forward and brutal fashion that leaves no room for nuance. Platoon is a film that you have to think about in order to attain its full affect, but it forces a different, more internally targeted type of thinking. Again, that’s the duality of Oliver Stone. He is a terrific film maker, and one of the things that makes him so terrific is that he forces you to rethink your preconceived notions, and that isn’t always comfortable for people. So the very thing that makes him a great film maker also makes him controversial and turns some people off to him.

One other quick thing I’d like to point out is the number of men in this film who would go on to have solid to stellar careers in Hollywood. Go to IMDB to look up any of these names, and you’ll find some very successful careers: Charlie Sheen, Tom Berenger, Willem Dafoe, Keith David, Forest Whitaker, Kevin Dillon, John C. McGinley, Mark Moses, Johnny Depp. Most of these guys had had some success in Hollywood already, but this film helped to launch many of their careers to the next level.

Finally, I would like to say this. I had not seen Platoon since I saw it in the theater the year it came out. I was so affected by it from an emotional standpoint that I couldn’t bear to put myself through it again until now. If you are like me and haven’t seen Platoon for a long time or if you’ve never seen it, it’s worth watching. IT is a powerful film and an important film, and it deserves to be seen and thought about.

Yes they did. There were some other good films nominated in 1986. Hannah and Her Sisters is considered by some people to be Woody Allen’s best film, but fortunately the Academy didn’t repeat the same mistake it did nine years earlier when Annie Hall beat Star Wars, because Hannah and Her Sisters isn’t close to being on the same level as Platoon. The Mission is another powerful film that forces us to look at our past and how many of our forefathers left behind a legacy that deserves another look. A Room With a View and Children of a Lesser God were both romantic dramas that were fine films, but were also not on the same level as Platoon, which I should add is also ranked 83rd on AFI’s original list of the 100 greatest films of all time. It was one of the top two or three films of the entire decade and the only real choice for Best Picture of 1986.

Over the weekend I took the opportunity to watch Red River, a classic Howard Hawks western starring John Wayne and Montgomery Clift. I had never seen it before, but it’s been on my list for a while, and it’s on many lists of top westerns. For example, AFI has it listed as the #5 western of all time. Over the past few years I’ve come to appreciate the western as a genre in a way that I never have before. This is probably a subject for another blog post, but I really believe that the western is currently the most under-appreciated genre in modern cinema.Like any genre, there are great westerns and there are westerns that aren’t so great. But what I’ve been discovering over the past several years is that many westerns have strong stories, complex characters with deep relationships, and strong themes that have resonated timelessly within our popular culture.

Red River is one such film that is an example of a good, actually great, western. It has a strong story and strong themes, and it has complex and deep characters, and the complex relationship between the two main characters is the driving force behind the story. Thomas Dunson (Wayne) sets up a cattle ranch with his friend Nadine Groot (Walter Brennan), and they’ve rescued a young boy named Matt Garth (Clift) who was on the wagon train with them when it was attacked by Indians. The ranch is successful enough, but the Civil War decimates the Texas economy and Dunson finds himself broke, but with 10,000 head of cattle. He figures he needs to drive them to Missouri so that they can be sold, so he recruits Matt, Groot and 10 others, promising them $100 each when the cattle are delivered. The trip is fraught with danger, with bandits, Indians and bad weather all along the way. They hear a rumor from a passing cowboy who lost his herd that Abeline, Kansas has a safer trail, but he can’t confirm that they have a railroad, so Dunson obsessively vows to press on. Dunson becomes so obsessive over the trip, that he ultimately loses his humanity and threatens to hang two men who stole some provisions and tried to head home. That’s too much for Matt, who wounds Dunson and leaves him with a horse, telling him to go home and that he’s going to take the herd to Abeline. Dunson then famously delivers the following line. “You should have let ’em kill me cause I’m gonna kill you. I’ll catch up with you. I don’t know when, but I’ll catch up. Every time you turn around, expect to see me. Cause one time you’ll turn around and I’ll be there. I’ll kill you, Matt.”

Here is a clip of the scene.

The rest of the film is spent with Matt trying to get the herd to Abeline and constantly looking over his shoulder while Dunson hires some men to help track him. Dunson started out as the hero of the story, and slowly slipped over to the other side. It wasn’t abrupt, and the audience can see it coming, which adds to the drama of the story. Hawks along with screenwriters Borden Chase and Charles Schnee show us a character right from the beginning who is straddling the line between heroism and villainy. He is a ruthless killer who gives his victims a proper Christian burial. He rides his men mercilessly, but when one of them is killed in a stampede he tells Matt that the man’s widow will receive his full share of payment at the end of the drive. He takes Matt into his home and raises him as his own son, but is ready to kill him over a perceived betrayal. We are presented with a deep character who is not dissimilar to any other hero. Many heroes are given these types of contradictions and have to face similar choices about doing right and wrong. Dunson just makes the wrong choices, and his obsession with getting the cattle to market over takes his senses and causes him to lose his humanity.

All the while we’re also getting to know Matt, and we come to like him as he attempts in vain to get Dunson to come to his senses. At the halfway point of the film, Matt becomes the hero of the story and Dunson has become the villain. This is a classic example of the archetypal Shapeshifter, with the Mentor/Hero becoming the Shadow and the Ally becoming the Hero/Enemy. What’s impressive about it is that it happens in a way that is organic and gradual. The audience watches it happen, and is rooting for Dunson to do the right things, and it creates dramatic scenarios when he doesn’t. Then while Matt is driving the herd to Abeline and constantly looking over his shoulder for the shadow of Dunson, it creates tension and suspense that even if Matt does accomplish his goal, he won’t be able to live to enjoy his success, so complete is Dunson’s descent.

Watching this film recently got me to thinking about other films with characters that have heroes who turn into villains and three of them came to mind immediately, with two of the films being very good, and the other one not so much.

The first film that came to mind was The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. Humphrey Bogart plays Fred Dobbs, an American who is down on his luck and stuck in Tampico, Mexico. After nearly getting cheated out of wages for a job-for-hire he and his friend Curtin (Tim Holt) hear that there’s gold in the Sierra Madre Mountains from an old timer named Howard (Walter Huston). Together, the three of them get the equipment they need and head up into the mountains. They do end up finding gold. In fact, they find a lot of gold, and it should be enough to make all of them very happy. Unfortunately, Dobbs starts to lose trust in his allies for no other reason than his own paranoia is taking over.

But what Director/Writer John Huston did that was so brilliant and accounts for the terrific storytelling in this film is that he made Dobbs completely likable and sympathetic in the first act. He’s a man who’s down on his luck and has resorted to begging from other Americans in Mexico. However, he leaps at the chance to earn an honest wage. Then when the contractor tries to get away without paying him, Curtin and Dobbs find him in a bar and beat him up, but only take the money that he owes them, when they could have taken a lot more. We’re shown in this scene that Dobbs is an honorable person who is willing to fight for what he believes is his. With this knowledge, we’re sent on the adventure of the men trying to find the gold, and once they start amassing their fortune, Dobbs slips slowly and surely into oblivion. By the third act, Dobbs’ paranoia has completely taken over. Gone is the honorable man who will fight to aid his friends only to be replaced by someone who sees treachery wherever he looks. He now believes he has to steal from his friends before they steal from him. Here is a scene that demonstrates that perfectly.

From here Dobbs’ paranoia turns into full-blown insanity, and he ceases being the story’s hero, and becomes its villain. Just like in Red River, the ally (Curtin) has now become the archetypal hero of the story and the character with whom the audience will identify for the rest of the story.

The other film that I thought of that does this switch very effectively is The Godfather. We are introduced Michael Corleone (Al Pacino) with his army dress uniform on with the pretty Kay Adams (Diane Keaton) by his side. He is the son of the Vito Corleone (Marlon Brando), the most powerful mafia figure in New York, if not the whole country. But he has not entered that life, and goes out of his way to tell Kay that he’s not involved. Then after an attempt on his father’s life, Michael heroically moves Vito to another hospital room as men are approaching to finish the job, and then even more heroically stands up to the crooked cop (Sterling Hayden) who was going to allow that to happen. He then risks his own life and sacrifices his future to kill the cop, as well as Sollozzo, the crime boss who ordered the hit on Vito. While in exile in Sicily, Michael meets and marries Apalonia, the daughter of a local cafe owner, and we feel sorry for Michael when she’s killed by a car bomb that was meant for him. But when Michael is called home after the brutal murder of his brother Sonny (James Caan), and he’s put in charge of the family business, we see Michael’s sinister nature come to the forefront. He settles the family business in the most brutal way possible.

That is only the beginning of the sinister nature in Michael that will carry the film’s sequel and culminate in Michael ordering the death of his own brother Fredo.

What all three of the above films have in common is that they all had characters that were likable, honorable and sympathetic, and all of the films took their time to effectively take these heroic characters and devolve them in various ways into villains who were willing to kill the people closest to them and the people who helped them attain what they’d been trying to do. The audience can feel the characters slipping away, and constantly root for them not to, and that is where the drama comes from. The fact that these films are so dramatic is what makes them so successful and gives them the ability to withstand the test of time.

The other film that I thought of that wasn’t as successful in this endeavor was Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith. Plenty of people have spent the last 17 years bagging on the Star Wars prequels, and for good reason. To say that they were disappointing would be an understatement, and to me there is one reason that they didn’t live up to expectations and that is because they lacked drama. The reason they lacked drama is because Anakin Skywalker was not sympathetic or likable as a character, so as an audience we didn’t care as he succumbed to the Dark Side of the Force. As a matter of fact, we really didn’t care about any of the characters very much, but it was crucial for us to at least care about Anakin in these films, and Director/Writer George Lucas failed to make that happen.

There are many reasons that we couldn’t connect emotionally with Anakin. I will never understand why George Lucas introduced us to Anakin as a boy in the first film, and then by the second film he was a grown man, but no one else around him had aged at all. When Hayden Christensen was introduced to us as Anakin in the second film, his brooding performance made a bad situation worse. I’m sure he was trying to capture the same magic that he had with Luke 24 years earlier, but he totally missed the mark. When we first met Luke, the best way to describe him was as kind of a brat. But what he had was wonder. In one scene, with him looking off to the dual sunset we saw a person who longed for adventure and for a better life. It was classic Hollywood cinema, and we were happy to go on that ride with him. We never got that moment with Anakin, and I think introducing him to us as a child played a part in that.

Personally, I’ve always thought that Anakin needed to be more like Han Solo. He needed to be a character that was witty and cocky. He needed to be a rogue and a scoundrel. He needed to have some type of personality, because the character that we were given had none. Then when you add in the factor that he had absolutely no chemistry with Padme (Natalie Portman) as Lucas tried to wedge a round-hole love story into the square peg of the rest of the film, you have a recipe for disaster. Even then, however, it could have been saved. The most important relationship for Anakin, and the character who was the most betrayed by him, was Obi-Wan Kenobi (Ewan McGregor in the prequels), and we needed to see a bond forged between these two characters that should have appeared to be unbreakable. Near the end of Revenge of the Sith, Obi-Wan, devastated by Anakin turning to the Dark Side, yells to him, “You were my brother, Anakin!” Really? They’ve hardly spent any time together over the course of the three films, and we’ve seen no real development of their relationship whatsoever. That moment should have been soul-crushing and heartbreaking. Despite McGregor bringing out everything he could in his performance it was neither, because the audience just hasn’t been given the opportunity to care about any of the characters or any of their relationships.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GLB57DOjA8k

Naturally, one of the key components to any screenplay is having a main character with whom the audience wants to follow on his or her journey. If you haven’t developed a hero who is likable or with whom they can at least sympathize, then no one is going to care what happens them, so no one will care about your story. It is especially crucial if you’re attempting to craft a script in which your hero turns in to a villain over the course of the story.

At Monument Script services, we pride ourselves on knowing how to craft well-developed characters for your stories. If you’re working on a script and you need your characters (or any other component of your script for that matter) evaluated, then please the link below to see which of the services we offer best suits your needs.

http://monumentscripts.com/

Spring is a time for new beginnings. With that in mind, Monument Script Services wants to help you get started on a new beginning for your screenplay by offering 20% off of any first-time coverage service between now and April 1st.

Having a professional reader evaluate your screenplay is an integral step in getting you script ready shop to agencies and production companies. Professional Readers like me have read for production companies and can provide you with first-hand insight on getting a PASS or a CONSIDER. Not only that, but getting an evaluation from a professional reader will also make you a better writer because he or she will assist you in improving your screenplay, which in turn will improve your writing and make your next screenplay that much stronger at the start.

No one can guarantee that your script will get picked up by a studio or an agency, but using a professional reading service like Monument Scripts can certainly increase your odds and give you an edge over the competition. There are a multitude of benefits to using, and now is a great time to get your script evaluated so that you’ll have time to make your improvements and get your script submitted before agents, executives and producers start taking their summer vacations.

Submit your screenplay to Monument Scripts between now and Friday and take that first step. Click the link below to see a list of our services and decide which is the best one for you.

As many sports fans know, the first weekend of the NCAA Men’s Basketball Tournament is one of the great weekends on the sports calendar. Sixty-four teams enter the weekend on Thursday with dreams of making it to the Final Four and sixteen teams remain with their dreams intact at the end of Sunday, with the rest going home disappointed and hoping for better results next year. There are many things that make the NCAA Tournament so great, and it deservedly has acquired the nickname “March Madness”. These teams are made up of kids between the ages of 18 and 22, so you never know how many of them will respond to adversity. Many of the big name schools have primarily younger players because the best players go to those universities and typically leave early to chase their NBA dreams. While many of the smaller programs have more veteran players who know they won’t be in the NBA and stay through their senior seasons. That means that many of the smaller programs have players who have played together for multiple seasons and have developed chemistry that many of the bigger, more talented, yet younger programs haven’t been able to acquire. That means you can have a team like Stephen F. Austin University pulling the upset over West Virginia, one of the top teams in the country all season. This weekend we also had one of the biggest upsets in the history of the tournament when Middle Tennessee State University knocked off Michigan State, a team that made it to the Final Four last season and that many picked would win this year’s tournament, in the first round.

A game was won this weekend when a player made a half-court shot at the buzzer, another player tipped in an offensive rebound with one and a half seconds left to win that game. Wisconsin won their game when a player made a fall-away 3-pointer as time expired, and Texas A & M made it to the Sweet 16 only after erasing a 12-point deficit in the last 33 seconds of regulation. It’s called March Madness because games are often won and lost on desperate miracles. This tournament is all about surviving and advancing. You win or you go home, and there are no second chances.

Okay, fine, you’re saying right now. But what does this have to do with screenwriting?

It has everything to do with screenwriting.

These games are one and done, which means you have to win if you want to advance. Since the games are being played by very young men, there is an air of unpredictability that heightens the drama to nearly unbearable levels, even for the most casual of fans. Many of the game are close, with the outcome in question until the final seconds, and that creates high entertainment value. This tournament makes for great theater, and the drama that it creates should be studied by any screenwriter. There are reasons that sports movies are popular, and here are five ways that screenwriters could learn from March Madness.

What puts the madness in March Madness is the possibility that almost anything can happen. The bracket is broken up into 4 regions of 16 teams each. About the only thing that’s never happened is a 16-seed beating a 1-seed, although Princeton came close to beating Georgetown one time several years ago. However 2-seeds have been upset by 15-seeds, as happened this year with Michigan State and Middle Tennessee State. Including this weekend’s upset it’s now happened seven times since 1991 when the Richmond Spiders took down might Syracuse. The unexpected nature of the tournament and the possibility that any team can win any game is undoubtedly one of the aspects of the tournament that keeps people coming back to watch every year. Even last season when Kentucky came into the tournament undefeated, there was still a belief that anyone could win it, and sure enough Duke upset Kentucky on the way to winning the title. One show that has successfully embraced a similar idea is Game of Thrones. It’s compelling television because they’re not afraid to kill off popular characters for the benefit of the story, and they’ve maintained, or perhaps even built, their popularity because of it. Think about your own screenplay. Is it predictable? Can you build a plot line into it that makes sense, but no one will see coming? Think about what a great plot twist can do for a movie. It’s the unexpected that gets people talking and remembering a story.

Piggybacking on that last point, underdogs have a chance to win games against more talented opponents through hard work, determination and resiliency. As mentioned earlier, many of these teams have players who know that they’re never going to play in the NBA, so they stay in school and on their teams the whole four years. That allows for many of these less talented teams to rely on teamwork and sound fundamental basketball. As the game wears on and a less-talented team continues to keep it close, you can feel their confidence rising, and you can feel the tension starting to build in the more talented team. You can feel the tide turning, and the drama building. But it’s slow. It’s deliberate. Sometimes, as with Middle Tennessee State against Michigan State it feels inevitable. Each time the more talented team looks like they’re going to pull away and win, the underdog hits a miracle 3-pointer to stem the tide. Each time it looks like the underdog is clearly on the way to an upset, the more talented team scores 6 points in a row to take the lead. It’s back and forth, and the crowd is standing and/or sitting on the edges of their seats. It’s riveting entertainment, and it’s exactly the way tension should be building in your screenplay. As you characters work towards their goals, the tension regarding whether or not they’re accomplishing their goals should feel the same way. The drama and the tension should slowly build with the advantage moving back and forth between your hero and your villain until you reach the climax and one of them finally has to win.

As all of the buzzer-beating, game-winning shots show us, the game isn’t over until the last horn sounds, the clock reads 0:00 and one team has more points than the other. Until the clock reads 0:00 anything can happen and, more often than not, does. This should teach screenwriters that before “The End” appears on the screen, they need to be open to anything. As mentioned above, constantly keeping the audience guessing is great, but this point goes even deeper than that.Screenwriting should be a creative endeavor done by creative people. Even when working within the bounds of dramatic structure, as a creative person the screenwriter should be able to imagine any kind of scenario that pushes the story forward and heightens the entertainment value to great and unexpected levels. A screenwriter also should be able to do this right up until the end of the story. Most stories end with some sort of denouement. There’s no need to lose the entertainment value there. In fact, since that’s the last thing that the audience will see, I could argue that the denouement needs to be among the most entertaining and compelling moments of your story. Just like the buzzer-beater in March Madness.

March Madness is a time when basketball heroes are made. It’s a time when largely anonymous basketball players instantly become household names due to their heroics on the court. Thomas Walkup of the Stephen F. Austin Lumberjacks was such a person. In their upset of West Virginia he made a name for himself and in their game against Notre Dame, he became a would-be hero hitting shot after shot and directing his team towards what looked like an improbably victory. However,, the hero doesn’t always win and when Notre Dame tipped in a shot with 1.5 seconds left, the hero of this story walked away the loser, but having earned the respect of the basketball world. Your screenplay needs to incorporate similar ideas with your main character. He or she starts out the story unknown to us as the audience, but her drive and determination endear her to us, and even if she doesn’t win at the end, we need to be shown that she’s still a stronger and/or better person because of the ordeal she went through. Even in defeat, many players in March Madness achieve some level of immortality. The same thing needs to happen with your characters.

Of course the tournament is an organic thing and the dramatic moments that occur happen spontaneously. But there is tension in many of these games and that tension leads to a feeling that something dramatic is unfolding in front of you while you’re watching it. That heightened drama helps increase the entertainment value of the games. The reason for that is because the stakes are so high, and they get higher the farther you get. You have to win six games to win the National Championship, and so each victory ratchets up the pressure, as well as the competition to continue winning. As you continue to win, the teams that you’re playing get better and better, so you have to keep upping your own game to keep winning. The same thing applies to your hero and to your villain. The closer each gets to their goal, the more important it has to be for them to keep upping their games. Each challenge that your hero faces needs to beget another challenge that is more difficult than the previous one. The stakes have to keep getting higher, and the drama has to keep increasing in order to keep the audience engaged. No on wants to watch a game that’s a blow out. It’s clear who’s going to win, so there’s no drama there. But a tight game that’s back and forth with teams exchanging leads is compelling, riveting and entertaining. It’s unclear who’s going to win, so we feel the need to keep watching in order to find out. If your hero or villain wins every confrontation, the same feeling sets in. The drama comes from not knowing how it’s going to turn out.

As the tournament’s nickname implies, March Madness is entertaining. It’s quite possibly the most entertaining sporting event of the year. Your ultimate goal as a screenwriter needs to be to entertain your audience. Watching and studying how the NCAA Men’s Basketball Tournament plays out gives you plenty of reference on what audiences are looking for, and how dramatic and exciting you can make your own screenplay.

Do you have a screenplay that is lacking in entertainment value? Let Monument Scripts review it for you and we can give you advice on how to apply these standards to your script. Click the link below to see which of our services is right for you.

There is so much more to writing a screenplay than just writing the screenplay. Before you ever get to writing scenes and dialogue, you need to spend hours and pages writing treatments and character biographies and answering series of questions on tone and mood, and just figuring out what kind of story you want to tell. Indeed, if you’re writing your screenplay properly, you’ll spend way more time doing the preparation than actually writing the screenplay. However, out of all of the prep work you can do, the most important thing to write before you write your script is an outline.

Treatments are great, and they certainly serve a purpose, though I’ve always believed that treatments are just as much external than internal. By that I mean that writing a treatment is providing a way to tell the story in prose form, and giving you a quick way to tell the story to someone without having to have them go through the exercise of reading the whole script. It’s also a good way to see in a big-picture if your story is working and how it flows before committing to writing it out in its entirety. However, an outline is just as effective, if not more so, in that regard than is a treatment. In fact, here are five reasons that an outline is the best of both worlds when it comes to developing your story.

An outline is a shorthand way to see your entire story. You can see right away how well the story is paced. You can clearly see if there are too many dramatic scenes in a row without and comic relief or action to break them up. If you write out your outline on note cards, you can change the order of scenes to experiment with the pacing to see if the story would work better that way. If the scene order is crucial, you can re-envision the scenes so that the way you tell those pieces of the story improve the pacing of the overall story.

Having strong and clear dramatic structure, especially for undiscovered writers who are trying to break into the industry with a spec script, is essential. If you’re shooting to have 25-30 scenes in your script (which you should be), you’ll be able to see that your target for ending Act 1 will be around scenes 5-7, the stakes in Act 2 should be raised around scenes 12-15 and Act 3 should begin by scenes 20-25.

In relation to example #2, you’ll be able to see if the adventure is beginning, the stakes are being raised and the hero loses everything in the appropriate scenes. Also, you’ll be able to easily look at the scenes of the story and see which scenes are moving the forward story and which scenes are not. You can then make a decision of those scenes can be reworked or should be cut before you waste a lot of time writing them.

Your story should ultimately be tracking the growth and/or character arc of your main character. When the entire story is there in front if you, you can quickly see where those character moments are and if they’re happening in appropriate places.

The outline allows you to see your entire story all at once. Combining the four reasons above leads to the overall realization that you can see your entire story at once. It allows you to see what’s working and what isn’t before you spend a lot of time writing scenes that might ultimately have to be cut. It allows your first draft to at least have the core of your story in place so that the your rewrites shouldn’t have to include major story changes.

Now, with all of that said, I should point out that you won’t be able to solve all of your scripts problems in an outline. Some of them just won’t be apparent until you actually write out all of the scenes and see where the story actually goes. However, an outline will show you the obvious flaws in your story so that those can be corrected and your later drafts will be about improving what you have rather than reconceiving what isn’t working.

Do you have a story that is in the outline stage, and you need it evaluated? We can evaluate your outline and let you know what to look for in terms of what’s working in your story and what isn’t. If you’ve already moved on to a treatment or are writing pages in your screenplay, we can help with that as well. Click the link below to see a list of our services.

http://monumentscripts.com/service/screenplay-coverage/