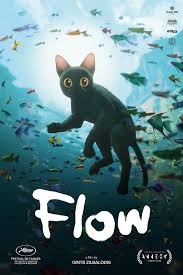

Imagine a screenplay without a single word of dialogue. Imagine further that screenplay telling a story so complete and compelling that it conjured up feelings of empathy and pathos that were so emotional as to keep the audience glued to the edge of their collective seats. Take it one more step and imagine that screenplay producing a film that beat films from powerhouse animation studios like PIXAR and DreamWorks to become the winner of the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature. If you imagined all that, you would come up with Flow.

Flow might be one of the most impressive cinematic accomplishments I’ve ever seen. This animated team made a film with hardly any money at a studio with hardly any people and produced a film that took the world by storm and awards season by the balls. This plucky studio and its pluckier film about a cat leading a band of misfit animals roared onto the scene like a lion and brought a tiger-like ferocity to the world of animation in a film that has all the emotion of the birth of a newborn baby. It might seem like I’m getting a tad hyperbolic, but it’s hard to overstate how impressive a work of art Flow is.

An underdog story about a cat

Why was Flow such a success? How did this simple film from a small studio in Latvia become such a worldwide sensation? The easy answer is that it had a great story. But what does that even mean? A great story is more than a compelling plot. As I tell screenwriting clients all the time, the plot is what happens, but the story is why we care. What can screenwriters do to get the audience to care? There are so many tools in the screenwriter’s toolbox that it’s impossible to name all of them. However, it’s easy to pick out what the filmmakers of Flow did. They included strong thematic components of coming together as a community to accomplish more than we could accomplish on our own and the idea of overcoming phobias and fears to make your life more complete and happier.

They also effectively utilized The Hero’s Journey to tell a riveting, dramatic story.

Warning! Spoilers!

Ordinary World

- The cat lives alone in a house surrounded by statues of cats.

- Humans used to live here, but for reasons we don’t know, they’re gone.

- A pack of dogs runs by. The cat steals a fish they caught before being chased away.

- We also see a flock of large secretary birds that will play a key role later in the story.

Call to Adventure

- The dogs run by the cat without giving it a second look, followed by a herd of deer.

- Flood waters carry the cat away.

- The cat gets to land with a friendly dog (a Labrador) from the pac,k and the Labrador follows the cat back to his house.

Meeting the Mentor

- The cat wants nothing to do with the Labrador until one of the secretary birds confronts him, and the Labrador barks it away.

Refusal of the Call

- They get back to the house, and the cat leaves the Labrador outside.

- The floodwater continues to rise. A boat flows by, and the Labrador encourages the cat to get in. The cat refuses after seeing the rest of the dogs on it, so the Labrador hops in, and they float away.

- The water continues to rise, and the cat gets as high as it can and sees a giant sea monster swim by, terrifying him.

Crossing the First Threshold

- Finally, a boat with a capybara flows by, and the cat hops on it.

Tests, Allis, and Enemies

- The cat is initially frightened of the capybara but quickly realizes he has nothing to fear.

- Rain comes in, and the cat must share a sheltered space with the capybara.

- The next morning, a flock of secretary birds flies by. One of them startles him off the boat, but the bird seems more curious than hostile.

- The cat tries to catch a fish but can’t and struggles to catch up with the boat.

- The sea monster swims by him, saving him from drowning, but he’s picked up and carried away by a secretary bird.

- The bird drops the cat and lands on the boat, where the other secretary bird stares him down before flying off.

- The cat takes control of the rudder from the capybara.

- They come aground at the home of a lemur, who has scavenged all kinds of shiny objects,

- They put them in a basket and the capybara drags the basket on the boat.

- The flood continues to rise, and the lemur jumps on the boat with them before looking longingly back at his flooded home.

- The capybara shows the lemur a mirror that was lying on the deck and the lemur loves it.

- The Capybara grabs a bushel of bananas and offers one to the cat, but he doesn’t eat them.

Approach

- The cat dreams about being surrounded by marching deer before a giant wave sweeps him away. He wakes up and steers the boat to shore.

- The lemur discovers a glass ball, like one that was in the cat’s house.

- The Labrador shows up and wants to play.

- The cat tries to catch fish but can’t.

- The secretary bird leaves him one until two more birds arrive and eat it themselves.

Supreme Ordeal

- The cat climbs a hill and sees a flock of secretary birds.

- The other animals rush up and knock him down the hill. and

- The birds get aggressive.

- The cat runs away, and the birds give chase.

- The one friendly secretary bird holds the others off, and the leader challenges him.

- The leader wins the fight and breaks the nice bird’s wing.

- The birds fly away. The nice secretary bird tries to keep up but can’t fly due to its injury.

- The cat befriends the secretary bird, and the bird joins the crew on the boat.

- They continue to flow down the river.

Reward

- The animals’ different personalities come out.

- They come across another boat, also with lemurs scavenging.

- The lemurs hop on board and want the mirror, but the cat chases them off.

- The cat shows trust in his crew for the first time.

- They come to some old ruins that appear to be a place they could stay.

- The dog is excited, wanting to play fetch with the bird, but the bird kicks the glass ball into the water, causing the lemur to attack it.

- The fight knocks the cat and the capybara overboard.

- They’re surrounded by fish. The cat marvels at them. The capybara tries to retrieve the ball, but the sea monster swims by, leaping into the air and almost capsizing them.

- The cat finally starts catching fish. He is out of his shell.

The Road Back

- They come across the pack of dogs stranded on ruins.

- The Labrador and capybara try to get the bird to sail to them.

- Finally, the cat agrees, and the bird relinquishes the rudder.

- They let the dogs on, and chaos ensues.

- One of the dogs breaks the mirror.

- The sea turns stormy, and the cat is knocked unconscious.

- He wakes up as the storm subsides, and the bird gets off the boat at the bottom of a cliff.

- The cat gets knocked off and chases the bird even as the boat sails away.

- The cat finds the bird as bubbles float in the air.

- The cat and bird are lifted off the ground as the bubbles turn into lights, and the heavens shine.

- The bird goes to the bright light in the sky as the cat falls back to earth.

Resurrection

- Left alone, the cat is on the same ground as his dream.

- He races back and swims to the boat.

- He latches on to the glass globe floating in the water and kicks towards the boat.

- The flood waters recede, and the cat is on solid ground.

- After searching, the cat finds the lemur’s basket and then finds a colony of lemurs.

- He’s not afraid of them. Then he finds his lemur, who initially stays but then follows the cat.

- They find the boat caught in a tree. They help the dogs out, and the cat leads them to hold the rope so the capybara can get out before the tree collapses into a ravine.

- The cat has gained real courage.

- The other dogs take off, and the Labrador wants to follow them but stays loyal to his real friends.

Return With the Elixir

- The new family celebrates as a herd of deer gallops by them.

- The cat follows them and finds the sea monster grounded and dying.

- The other animals catch up, and the cat looks at his reflection in a pool of water.

- The others join him, looking at their new family.

There it is—a complete Hero’s Journey and a complete 90-minute film without a single word of dialogue. This story has everything a story needs: emotion, suspense, humor, pathos, and hope. The protagonist experiences a complete character arc matching the story’s strong thematic components. And the story is told 100% visually.

This is a film that any screenwriter or filmmaker should study when they want to learn the art of visual storytelling.