“Jerry, don’t let’s ask for the moon. We have the stars.”

Screenplay by Casey Robinson

“Jerry, don’t let’s ask for the moon. We have the stars.”

Screenplay by Casey Robinson

“If you’re nothing without the suit, then you shouldn’t have it.”

Screenplay by Jonathan Goldstein, John Francis Daley, Jon Watts, Christopher Ford, Chris McKenna, and Erik Sommers

I evaluated a script and provided coverage last week that made for an interesting read, as well as a couple of interesting dilemmas. The screenplay was entertaining enough. It was an action script that was well-paced, but not particularly well-structured. It had a very short first act and there was no discernible break between the second act and the third act. The story did change direction somewhat at the point where the break should have been, but there was no emotional connection in regards to it with the main character, and that left the moment wanting. I have had other such experiences while reading scripts, and those instances confirm to me how interconnected the structure of a story is with the development of the main character.

If the main character doesn’t have a clear goal that the audience can be emotionally engaged in, then the story will not hit the correct emotional beats and the entire structure of the story will suffer.

That might sound like a simplistic idea, but many writers struggle with the Act II to Act III transition and the reason for that almost always is because they didn’t do enough to develop the main character and make it clear what her goal was and what the stakes were. That’s a huge problem because the transition from Act II to Act III is all about the stakes. The best Act II’s end with the hero losing everything. Well, if you don’t know what’s important to the hero and why it’s important, how can she lose everything when we don’t know what she has to lose?

Getting back to the script that I read last week, that was the problem I saw. As I said, it was an action script, and there was a lot of action. It was entertaining, and if it ever gets made, it has the potential to draw a major star to the lead role and that could be enough to make it a hit. But I guarantee that it will have a crappy score on Rotten Tomatoes, and people might not even know why they’re down on it. I must admit, when I first read it, I couldn’t figure out why I was down on it either. Entertaining story? Check. Likable main character? Check. But why did I like him? He had some snarky one-liners and he killed bad guys. And yes, the story was entertaining, but the structure was all off and that killed the drama which killed my ability to become emotionally engaged. It was all superficial.

After going through the script a second time it dawned on me that the hero’s outer goal and inner need were both vague at best and nonexistent at worst. To a degree, I believe that the writer outsmarted himself by adding in a lot of misdirection and some “red herrings” in order to keep the audience off the trail of the twist that he was trying to set up for the end. Unfortunately all of that extra material muddied the water to the point where it was unclear what the hero needed to accomplish.

Now, I get it. This was an action script, and you’re thinking that an action hero doesn’t necessarily need an inner need that’s in conflict with the outer goal. I would counter that an action hero needs that more than anyone. Think of Indiana Jones. At least in the first three films of that series, he had an inner need that was in conflict with his outer goal. In the first film, he needed to reconcile with Marion so that he could make peace with himself over how he left her in the past. That comes into conflict with his outer goal of keeping the Ark of the Covenant from the Nazis when he finds Marion in the Nazi camp and is about to rescue her. He realizes that he can’t cut her loose because if she’s discovered to be missing, the Nazis would be alerted to their presence in the camp, and make it more difficult to acquire the Ark. In the third movie there is a similar situation, but he has to reconcile and salvage his relationship with his father.

Spielberg didn’t spend a ton of time on these motifs, but they were clearly there, and they added emotional impact to the story so that we as the audience were affected when we thought Marion was dead or when we thought that Henry was in danger of dying. The point is that, not only with hero’s in an action movie, but with any hero in any kind of story, the dramatic structure is directly tied to the wants and needs of the hero.

That simple formula is the basis for the drama in your story and without drama, there is no emotion. Again, it might sound simple, but just giving a character something to want isn’t enough. We need to know what the hero will lose if she doesn’t get what she wants and why that’s important enough for us to care about it. Will the Nazis get the Ark and use it to conquer the world? Will a group of children be sentenced to a lifetime of slavery so that a religious zealot will acquire what he needs to shroud the world in darkness? Or is it something simpler? Will the boy not get the girl, causing both of them to live a life where they’re constantly asking themselves, “what if”?

Whatever the answers to those questions are, the audience needs to care about it more than anything or your script, no matter how entertaining it might be, will be shallow, superficial and have the feeling like something is missing, like having an itch that can’t be scratched.

At Monument Scripts, we’re experts in story structure and character development. If you have a script that you’re working on and you are having issues developing your hero or finding the structure in your story, we can help. Click here for a list of our coverage services, and let us know which one best suits your needs and the needs of your script.

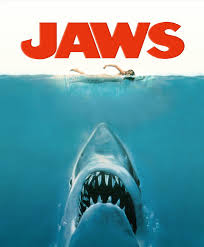

Oh, my god, this film is so fucking good. It’s impossible to overstate how excellent of a film Jaws is, and how important it was in the history of cinema. Rarely is there such a confluence of such greatness and such historical importance in a single film, and Jaws hits all the right notes. It’s ranked #48 on the original AFI list of the top 100 movies of all time, and my own personal list has it in the top 5 most important films of all time. It is not hyperbolic to consider Jaws as being at least as culturally important as Gone With the Wind, The Godfather, Star Wars, Titanic, Avatar or any other film that you’d care to mention. Jaws was the first summer blockbuster, it made Steven Spielberg’s career possible, it demonstrated how important the musical score can be to a film, and it literally made large swaths of the population afraid to swim in the ocean.

Jaws is one of those textbook films that has all of the components working equally and at a high level. The structure of the story is perfect, the pacing of the storytelling and the action makes this one of the most entertaining films ever made, the music accentuates the mood as well as the story telling, and the acting is nothing short of superb. Am I being hyperbolic? Perhaps, but I don’t think so. Jaws is a film that works incredibly well on many levels and holds up for reasons that are ironic, and yet reasonable.

Everyone knows the story about how the mechanical shark didn’t work. I recommend seeing the documentary The Shark is Still Working, if you’ve never seen it before. One of the topics it discusses is the fact that the mechanical shark’s continued malfunctioning actually ended up helping the film in the long run because Spielberg was able to use the fear of the unknown to his advantage by not showing the shark. Indeed, the actual screen time for the shark is very low, and not being able to see it, subconsciously makes it much more frightening. The scene where the shark jumps onto the boat looks campy by today’s standards, and the film would have suffered if a the mechanical shark kept showing up and looking unrealistic. But because we see so little of it, we need to use our own imaginations to fill in the blanks, and that allows the tension and the fear factor of Jaws to hold up to this day.

A little over a year ago I screened Jaws for about 25 people, about half of whom had never seen it. I know it’s hard to believe, but there are quite a few people out there who have never seen Jaws. It was great for me, because I’d seen the film so many times, and I can’t recall the previous time that I would have seen it with someone who hadn’t seen it before. Well, I can tell you that the horror holds up, because there are screams and squeals at all of the appropriate times, and people were genuinely affected by the film when it was over. Right from the inciting incident when Chrissie Watkins becomes the shark’s first victim less than five minutes into the film, and all the way through the end, the adventure and the horror and the drama mix together to create an entertaining and powerful film.

From a screenwriting standpoint, Jaws is a film that aspiring screenwriters should study. It has an excellent structure and a complete Hero’s Journey. In fact, there are individual scenes and sequences that have perfect 3-Act structure and Hero’s Journeys contained within them, one of which I blogged about here last year. The hero of the film is Chief Martin Brody (Roy Scheider), a New York City native who has transplanted himself to Amity Island, a Cape Cod-like resort community that relies on summer tourism for its very survival. Chief Brody’s Ordinary World is as the police chief of this small town. His Call to Adventure is the discovery of Chrissie Watkins’ remains and the Refusal of the Call is when he’s told that her death was the result of a boat accident and there’s no need for the beaches to be closed. Brody Crosses the First Threshold when young Alex Kintner is killed by the shark in front of several people and now there’s no mistaking that they have a shark problem that needs to be dealt with.

The Meeting of the Mentor usually happens in the first Act, but it’s in the second act in Jaws, and it’s the introduction of Quint (Robert Shaw), a local fisherman who offers to kill the shark for $10,000, much more than the $3,000 bounty that Mrs. Kintner is offering. The Tests, Allies and Enemies portion of the script introduces us to Matt Hooper, Richard Dreyfuss), and shows the various tests that Brody and Hooper go through find out what kind of Shark they’re dealing with. That is the crux of Act IIA. The Approach is the scene in which Brody and Hooper try to convince Mayor Vaughn (Murray Hamilton) that the shark is a Great White and that needs to be dealt with. The Supreme Ordeal is the scene that I linked to, and it has the shark actually attack the island and Brody’s family is directly impacted. That moves us into Act IIB, and the Reward stage of the Hero’s Journey in which Brody finally has the support of Mayor Vaughn to close the beaches and get Quint to help him kill the shark, which is the crux of Act IIB.

By the time we get to The Road Back portion of the story, we enter Act III, and the Shark has seemingly won. Quint’s boat is practically destroyed and the shark has proven to be seemingly indestructible. Act III becomes about survival in the Resurrection stage as the three men, who had been rivals, now must work together to defeat a common enemy. Brody finally kills the shark after the shark had killed Quint, and the Return with the Elixir shows that Hooper and Brody survived, and can return to the island safely.

What the storyline has in its premise is the basis of terrific drama. This small community relies on summer tourism in order to survive. I grew up on Cape Cod, so I know what that is like. In the film, a shark threatens that tourism business, and that forces the people in the story to act. They can’t just stay out of the water until the shark goes away. They have to be proactive and take care of their own problems for the sake of their economic survival. That is the basis of great drama.

What’s more is that the hero has to confront his greatest fear in order to do so. Chief Brody is afraid of the ocean and afraid to go on boats. But in order to kill the shark, he must confront both of those fears. Quint also goes through a great character arc. He starts the story out as cocky and arrogant, but the shark humbles him by the end, though it’s unfortunately too late for him. But the change in Quint is great because it’s subtle and happens organically within the confines of the story. It isn’t contrived to fit into the narrative. The narrative allows it to happen.

Finally, there is the music. The theme to Jaws is one of the most recognizable movie themes in the history of cinema, and Spielberg used it expertly to help craft the narrative. The music cues do more in this film to tell us when to be scared, when to be excited, then most films do.

Basically Jaws is a badass film. I’m sure there are many people out there who haven’t seen it, and if you’re one of those, it should go to the top of your list of films to see. It’s one of the most complete films that I’ve ever seen, it’s definitely in Spielberg’s top 3 of all of the films that he’s ever made, and it’s quite frankly one of the most entertaining and seminal films of all time.

Most professional writers won’t send a script to a producer without first having it read by a professional reader. Professional coverage gives any writer—no matter how seasoned or experienced—an essential tool to fine tune their work.

If your screenplay is ready to send to producers or agencies or even festivals—there is one big reason why summertime is the best time to have your script evaluated by a professional reader.

Everyone is on vacation

Summer is a rotten time to submit your script to studios and agencies. Everyone is on vacation. It’ll just sit on the bottom of an ever-growing pile of scripts.

Instead of letting it linger there, send it off to script summer camp where it can be evaluated by a professional—someone who knows what to look for and how to fix what needs fixing. You’ll get a new perspective and you’ll have the rest of the summer to make it shine.

When Labor Day is in the rear-view-mirror, everyone will be back at their desks and ready to look at new material—and your freshly polished script will be at the top of the pile.

If you think your script is ready to submit, use this summertime lull to get professional coverage from someone whose fresh—and experienced–eyes can help you make it better, stronger, tighter. Get polished, professional notes from Monuments Scripts now so that you can spend the summer getting your script ready for its best chance of getting noticed come autumn.

Submit your script between now and the summer solstice (June 20), and we will give you 10% off any first-time screenplay coverage service. We offer a variety of coverage packages tailored to where you are in your writing process. Find out more here.

Three hundred lives of men have I walked this Earth, and now I have no time.

Screenplay by Fran Walsh, Philippa Boyens, Stephen Sinclair, and Peter Jackson

What did you do, wake up this morning and say, ‘Today, I’m going to ruin a man’s life?’

Screenplay by Diane Thomas

Well, I think that when statesmen forsake their own private conscience for the sake of their public duties, they lead their countries on a short route to chaos.

Screenplay by Robert Bolt