“Now I have a machine gun. Ho, ho, ho.”

Screenplay by Jeb Stuart & Steven E. de Souza

“Now I have a machine gun. Ho, ho, ho.”

Screenplay by Jeb Stuart & Steven E. de Souza

Emotion is the lifeblood of your screenplay. That might not seem like such a bold statement to make, but you would be astounded how many films are missing that key component. This is especially true in genre films, like action, horror and comedy. The writers of those scripts and the makers of those films are (understandably) more concerned with getting thrills, chills and laughs in their respective genre, so not a lot of emotional development occurs within the characters or the story. That’s usually fine for a genre film, because you’re going to see them precisely for the thrills, chills and laughs that they provide. However, there are some genre films that go the extra mile and do create that emotion. What I mean by that is that they provide emotional connections with the audience that turn them from good or even great action or horror or comedy films, into films that transcend their genre and become all-timers.

This idea came to me as I was listening to the Third and Fairfax podcast. This particular episode had Brian Gary interviewing Scott Frank, who most recently wrote and directed the Netflix series Godless, but has a long list of screenwriting credits, including Get Shorty, Minority Report, The Wolverine, and Logan. Over the course of the interview, he discussed how reticent he was initially to work on The Wolverine because he wasn’t a fan of comic book movies and really didn’t know a lot about them. It also seemed like he knew that they missed an opportunity with The Wolverine, so he was even more reticent to work on Logan, but he was given certain assurances about how the script could be written and how the film would be made, and he seems to be much prouder of his work on the latter film.

One word that Frank kept coming back to over the course of the interview, whether he was discussing The Wolverine and Logan or Minority Report or any other of his past projects, was the work emotion. Where is the emotion coming from? What set of circumstances in this story will get an emotional reaction from the viewers? For the character of the Wolverine, it was the idea of facing his own mortality. For Chili Palmer in Get Shorty, it was being a huge movie fan and getting a behind-the-curtain look at the business. For John Anderton in Minority Report, it was becoming a victim of his own program. What these films have in common is that they’re all genre films (Action, Comedy, Science Fiction), but they all were successful beyond their genre because the emotional component that was added to the film attracted a wider audience than just those who are fans of that particular genre.

I was thinking about this the other day as I was going through some of my old Best Picture blogs. There have been eight films that you could call either action or adventure to win Best Picture. Four of those winners came between 1995 and 2003 (Braveheart in 1995, Titanic in 1997, Gladiator in 2000, The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King in 2003). I wouldn’t actually call Titanic an action movie in the purest sense of the term. The first half of the movie is a straight drama, but once the ship starts to sink, it turns into straight action. Other action/adventure Best Picture winners include The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), Ben-Hur (1959), Lawrence of Arabia (1962), and The French Connection (1971). As I thought about the winners from the nineties and 2000’s, and then also about the earlier films, I realized that the one thing they all have in common is that, along with being spectacular action films, they all have emotional components to them that allow the audience to engage emotionally with the characters and really care what’s happening, as opposed to just being along for a thrill ride.

It really hit me as I was thinking about two films, in particular. The Return of the King is the final installment of the Lord of the Rings trilogy and there are several characters whom we’ve been following throughout the series. We’ve learned much about all of their personalities, their flaws, their fears, and their desires. For example, Frodo, the unlikely hobbit who’s tasked with taking the Ring to the land of Mordor in order to destroy it by casting it into the fires from whence it came, turns out to be a character of immense bravery and strength. He goes on this adventure reluctantly, and is always pining for home. Since hobbits are like miniature versions of humans, Frodo and his friends have a natural inferiority complex that leads them to believe they can’t accomplish as much as men. This inner struggle inspires the hobbits to excel beyond what they believe their limits are. When Aragorn finally accepts the crown to become the king of Gondor, the hobbits all bow before him, and in one of the most emotional moments of the series Aragorn says to them, “My friends, you bow to no one.”

Speaking of Aragorn, we learn early on that it was his ancestor, who generations earlier, was unable to destroy the ring when he had the opportunity to do so, and that led to his downfall. Aragorn fears that since the same blood flows in his veins then the same weakness may also. He is reluctant to take his rightful place in the world. That very human trepidation that Aragorn has creates an emotional bond with the audience, even though his issues are fanciful to the rest of us. None of us are ever going to become king, but all of us have felt some unease about our place in the world or in our profession or in life in general. Many of us may even feel unworthy of what our destinies may be, and that lack of self-worth holds us back, just like it’s held back Aragorn.

Braveheart is the other example. Mel Gibson directed and starred in this film about a simple Scotsman who ended up leading a revolution against the British king. William Wallace (Gibson) wants nothing more than to raise crops and a family, but that all changes when the woman he loves is killed by the English soldiers occupying his town. From that point on, the movie is filled with blood and carnage and adventure, but the first 40 minutes of this film are spent allowing us to get to know William and his love Murron and his friend Hamish (Brendan Gleeson). We get to see their relationships develop and we get to see the bonds they have with each other, and we care about them. We have an emotional attachment to them.

The other action films on his list have many of the same components, whether it’s Judah Ben-Hur being betrayed by his childhood friend, T.E. Lawrence proving to the generals and to himself that he’s a good soldier, or Maximus avenging the brutal slayings of his wife and son, we care for and root harder for these characters because of that emotional component.

If you are working on a screenplay and you believe that emotional component is missing, try one of our coverage services at the link here, and we can help you find the emotional key that will unlock the emotion in your story and open it up to a wider audience.

I initially wrote this blog for nightowltv.com and it first appeared on November 2, 2017. Click the link for more from them.

1964 was a good year for cinema. Goldfinger, arguably the greatest James Bond film of all time, was released during the year, as were several other classics and borderline classics like A Fistful of Dollars, Marnie, Zulu, The Night of the Iguana, and A Hard Day’s Night. There were three films that were all nominated for Best Picture, that rise above every other film released that year. Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb is one of my personal favorite films, and the film that I would have voted for had I had a vote for Best Picture in 1964.

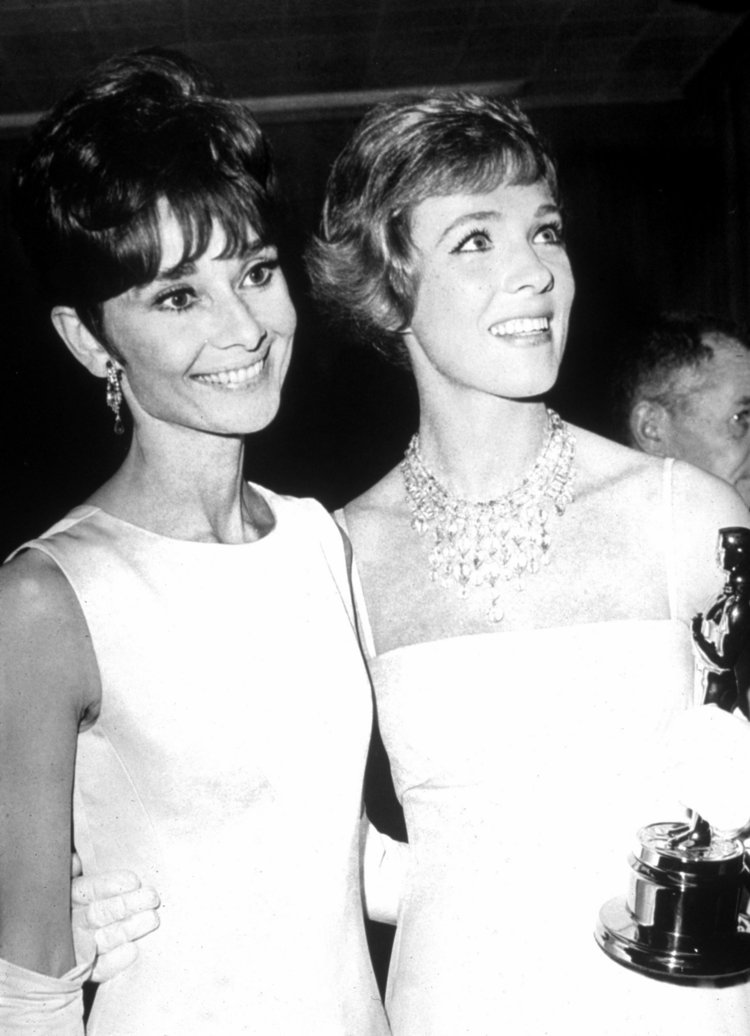

The other two films were musicals, and both are considered to be among the greatest musicals of all time. My Fair Lady had a very good Oscar night taking home eight statues out of 10 nominations, with wins for Best Picture, Best Actor (Rex Harrison), Best Director (George Cukor), and others. Mary Poppins wasn’t far behind with five Oscar wins, including Best Actress (Julie Andrews), Best Song (Chim Chim Cher-ee) and Best Music.

Yes, My Fair Lady won Best Picture, and yes, My Fair Lady is on the AFI list of the Top 100 movies of all time, coming in at #91 and Mary Poppins is not on that list. However, interestingly enough, Mary Poppins is ranked higher than My Fair Lady on AFI’s list of the Top 100 Musicals of all time, coming in at #6 vs. #8.

Agreeing with the latter assessment, I am here to tell you that Mary Poppins is a better movie than My Fair Lady and it was the best musical of 1964. Here are five reasons why that’s true.

There is no question that in 1964 Audrey Hepburn was a huge star, having already starred in such iconic films as Breakfast at Tiffany’s, Roman Holiday and Sabrina. Julie Andrews had made a name for herself playing Eliza Doolittle in the Broadway version of My Fair Lady, but Jack Warner wanted a star for My Fair Lady, and Julie Andrews had not starred in a feature film at that point. There were few stars bigger than Audrey Hepburn, and her grace,charm and wit certainly helped make Eliza Doolittle into one of the most beloved and recognizable characters in the history of American musicals. The problem I have is that Hepburn didn’t do any of her own singing. She could sing and was reportedly furious when she was told that her voice was not strong enough to do the singing for the picture. While her overall performance is terrific, the fact that the studio wouldn’t let her sing is a major issue, in my opinion, since singing is such a huge component of her character.

On the other hand, making her big screen debut and earning a Best Actress Oscar in the process, Julie Andrews turned the role of Mary Poppins into one of the most iconic characters not only in the Disney roster, but in all of cinema. This role would also give Julie Andrews one of the most successful screen careers of the second half of the 20th Century. Walt Disney reportedly could not listen to her sing Feed the Birds without being moved to tears, and her renditions of Spoon Full of Sugar, Jolly Holiday, and Supercalifragilisticexpialodocious along with Feed the Birds showed a range of singing, acting and dancing that Hepburn simply could not match. Andrews could be equally charming and stern. Not only that, but the character of Mary Poppins is a stronger, more confident driver of the action, whereas Eliza Doolittle mainly reacts to things happening to her.

Give me Julie Andrews over Audrey Hepburn in 1964 every time.

Both films showed somewhat misogynistic men overcoming their old fashioned ways to discover their priorities had been completely askew. I would argue that the character growth of George Banks is more profound and more sincere than the growth and change of Henry Higgins. The thing is, Higgins starts out the film as a total cad. He is an arrogant, smug, cocky jerk who gets his kicks out of messing with people’s lives. By the time he gets his act together and realizes that he’s in love with Eliza, I personally couldn’t care less whether he ends up with her or not. Eliza, for her part does want him, but she deserves way better. Once the story is resolved, there is no emotional impact.

George Banks, on the other hand, doesn’t necessarily start out Mary Poppins as the most likable character, but he’s at least doing what he ought to be doing, or what he thinks he ought to be doing to take care of his family. He later discovers that he’s missing out on the most important and most rewarding parts of being a father if he doesn’t change his ways. In what is some of the most emotionally impactful story-telling I’ve ever seen, George Banks becomes the father that he never knew he could be.

My Fair Lady has some great and recognizable songs like The Rain in Spain, I Could have Danced All Night, and Get Me to the Church On time. The top songs from Mary Poppins were mentioned above, but there are other memorable numbers like Stay Awake, Sister Suffragette, Step in Time. . What separates the songs in Mary Poppins versus My Fair Lady is that the songs from the former do a better job of moving the story forward or showing character. In fact, Bert, the chiminey sweep (Dick Van Dyke) uses the Spoon Full of Sugar reprise to finally show George Banks how he’s missing his children’s childhood, creating a moment of catharsis for George. The same argument could be made that Henry Higgins has a similar epiphany when he sings I’ve Grown Accustomed to Her Face. But, I think, like almost everything else in this film, it takes too long and is too drawn out to the point where boredom overcomes any dramatic impact that’s being made.

Both of these films are long. Mary Poppins comes in with a running time of 139 minutes, so it’s a little more than two hours. My Fair Lady comes in at a whopping 170 minutes, just 10 minutes short of three hours, and takes too long to get moving. While there is a lot of singing and character exposition, we’re a good 40 minutes in before the story really gets going. The length of the film has a negative impact on the drama in the story, and I find myself just not caring about the characters. Mary Poppins, on the other hand, is 30 minutes shorter and has a much tighter story that is paced better and doesn’t give us the same kind of long gaps in story points that cripple the story in My Fair Lady.

Piggybacking on the previous point, Mary Poppins is just a more entertaining film than My Fair Lady. It has a better story-line, it has better songs, and it has better pacing. It also has characters that we care about more than we care about the characters in My Fair Lady. It has better art direction, and it casts a much wider net in terms of cinematic techniques and language. Mary Poppins is a veritable smorgasbord of film making styles and techniques, using animation and cutting edge special effects to help enhance the story. Mary Poppins is a feast for the eyes as well as for the heart.

“Faith is believing in things when common sense tells you not to. “

Screenplay by George Seaton

“Six bucks and my right nut says we’re not landing in Chicago.”

Screenplay by John Hughes

I initially wrote this blog for nightowltv.com and it first appeared on October 18, 2017. Click the link for more from them.

Jack Lemon and Shirley MacLaine in Irma la Douce (1963)

What would the world of American Cinema in the second half of the 20th Century have looked like if Shirley MacLaine hadn’t been in it. I daresay, it would have looked substantially different. She’s one of only 8 actors to have appeared in 3 Best Picture Winners (Around the World in 80 Days, The Apartment, Terms of Endearment), and she has consistently been recognized as one of Hollywood’s top actresses since the late 1950’s. While some may feel that she may not have the acting prowess of Meryl Streep, or the girl-next-door quality of Sally Field, or the box office draw of Faye Dunaway, or the sex appeal of Marilyn Monroe, she had enough of each of those components to be regarded as one of the most well-rounded performers in Hollywood history.

MacLaine as Charity Hope Valentine in Sweet Charity (1969).

For people who might have arrived late to her party, one would think that MacLaine excelled at playing crotchety old biddies (Steel Magnolias, Guarding Tess), and since I myself was late to the party, that is how I thought of her for a long time. As I was able to see more films that she had been in, especially when she was younger, I discovered that Shirley MacLaine was an actress of exceptional range, surprising vulnerability and a dynamic sense of comedic timing mixed with dramatic gravitas that allowed her to play almost any kind of role. Indeed, just look at her performances in The Apartment where she starred opposite Jack Lemon and Terms of Endearment where she was opposite Jack Nicholson. You won’t find two Jack’s more different than those two, but she was equally comfortable with each of them, and built amazing on-screen chemistry with them both. In my opinion, only Meryl Streep, and perhaps Kathrine Hepburn, can match Shirley MacLaine in sheer range and quality of performances within that range.

So where to start if one would like to become more familiar with Shirley MacLaine but doesn’t know much about her career? Here is my Top Five list offilms starring Shirley MacLaine to become familiar with her as an actress, and to gain a good understanding of some of the greatest and most important films Hollywood has ever produced.

I’m guessing I’m going to get some blowback over this one, but bear with me for a moment. Her portrayal of the surly and salty Ouiser Boudreaux is one of the funniest performances she’s ever given. She is the perfect foil to the sweet and genteel women that populate this picture, and Oiser’s back-and-forth’s with Clairee Belcher (Olympia Dukakis) are comedic gold in what is generally considered a relatively emotionally heavy picture. The film itself isn’t remarkable, but MacLaine’s performance in it makes it worth watching.

Based on the book by Carrie Fisher, this is a film that is loaded with interesting themes and it’s filled with heart and wit and charm. Shirley MacLaine shared the screen with Meryl Streep, and those two powerhouse actresses filled that screen with star power, but more importantly, they filled it with amazing performances that only the two greatest actresses of the second half of the 20th Century could deliver. The case could be made that Doris Mann (MacLaine) served as the antagonist to Suzanne Vale (Streep), even though Mann is Vale’s mother. But at first, Doris is standing in the way of Suzanne getting what she wants, and must overcome her own demons to allow Suzanne to achieve her goals. This is a story about mothers’ relationships with their daughters, and overcoming their demons that hold their kids back.

MacLaine would win her only Oscar for Best Actress for her performance in this picture as the overbearing mother of Emma (Debra Winger) and the reluctant girlfriend of Garrett Breedlove (Nicholson). Playing the no nonsense Aurora Greenway, MacLaine gave one of the great performances of her career and Aurora was certainly one of her deepest characters. Starting out the movie as her daughter’s best friend, having spent a lifetime raising her as a single mom, Aurora developed a tough outer shell that she needed to use as a defense mechanism to protect herself and her daughter from any dishonest interloping man that tried to court her. But now, as Emma has created a family of her own, Aurora finds herself the target of the affections of Breedlove, a retired astronaut and incurable playboy. And yet, he provides for her a pillar of strength that she never knew she needed, especially when Emma is diagnosed with terminal cancer, and he extracts from her the gentle vulnerable woman that she forgot she could be.

This is a wonderful film in which MacLaine stars opposite Peter Sellers, who plays Chance, the dimwitted gardener who only knows life from what’s on television, and whose simplistic views on life fool everyone around him into believing that he’s something much more than he really is. The first person to be taken by his charms is Eve Rand (Shirley Maclaine), the younger wife of a dying, but obscenely wealthy industrialist. After her chauffer accidentally bumps into Chance with her car, she offers to take him to her house to recuperate, and once there, he finds himself casting influence all the way up to the highest points of power, including the Oval Office. MacLaine gives one of her most emotionally vulnerable performances as a woman attracted to this new man in her life as her loveless marriage is coming to an end, but her loyalty to her dying husband prevents her from consummating her feelings. However, the scene where she masturbates in front of Chance because he says to her, “I like to watch” is one of the great moments of Maclaine’s career.

If Being There was among MacLaine’s most vulnerable performance, then her performance in The Apartment was far and away, her deepest, most touching and most vulnerable performance. In this film, she plays an elevator operator who becomes suicidal after she realizes that the man with whom she’s having an affair (Fred MacMurray) doesn’t feel as strongly about her as she does about him, and he’s not going to leave his wife for her. MacLaine played this role with a spunky sensitivity of a girl with a hard outer shell but a center that was far too soft to cope with the emotional manipulation she suffered at the hands of an older and much more experienced man. For her efforts, and at the tender age of 26, MacLaine would receive an Oscar nomination for Best Actress in a Leading Role, and she was well on her way to super-stardom.

Honorable mentions: The Trouble with Harry, Can-Can, Guarding Tess

“The only word for this is… transplendent. It’s transplendent!”

Screenplay by Woody Allen & Marshall Brickman

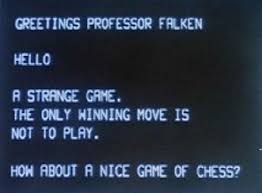

“A strange game. The only winning move is not to play.”

Screenplay by Lawrence Lasker & Walter J. Parkes

Film Noir is one of the most misunderstood genres of cinema. It’s so misunderstood that its referred to as a genre, when it actually encompasses many genres. Film Noir is really more a style of film making rather than a genre. Similarly, to Animation (Sing is a musical and King Fu Panda is an action/comedy, The Iron Giant is action/sci-fi) there are several different genres that could find a home within that style of film making. Yes, there are certain motifs that fall within it, like cops, private eyes and femme fatale’s, but you couldn’t look at films like Sunset Boulevard, Mildred Pierce, The Killing, or The Maltese Falcon and think that any of them share a genre, and yet they’re all referred to as Film Noir. In fact, the term Film Noir wasn’t even widely used until the 1970’s, a couple of decades after many of these films had first been released. When these films came out in the early 40’s through the mid 50’s, most of them were referred to as melodramas.

Gloria Swanson in Sunset Boulevard (1950)

There are several motifs that make Film Noir such a compelling style of film making. The first thing that many people think of is the femme fatale. Many of the greatest Film Noir have a strong female antagonist who leads a man with loose morals astray. Another popular component is the extreme light and shadow that was heavily influenced by early German expressionism film making of the 1920’s. With a couple of notable exceptions, most of the films take place in gritty, urban settings, and those qualities often inform the types of characters and situations that we’ll be experiencing as the audience. The case could be made that Los Angeles and New York are often, themselves, characters in these melodramas. Each of those cities carries with it a vibe and a personality that often plays a role in the stories in which they’re set.

Gene Tierney in Laura (1944)

Also, many of these films involved subject matter that was frowned upon by the Production Code and the Catholic League of Decency, so the producers of these movies had to be very creative about how they got their subject matter in. That led to a lot of subtext and creative cinematography that helped to make these films as timeless as they’ve become.

Why then, did the late 50’s spell the end of the Noir period? The answer likely lies in two places…

Technology in film making was taking the art to new places with color becoming much more prevalent and wide screen formats becoming a necessity to compete with the growing popularity of television. Since color and wide screen were so new, they were often used to show how polished and beautiful the world could be, and the often dirty and gritty settings of Film Noir just didn’t translate to that format.

Also, by the time the sixties rolled around, a new and freer style of storytelling was happening. Film Noir relied a lot on nuance and subtext, those notions were becoming less necessary and more corny and square as more “honest” films like Midnight Cowboy and Bonnie and Clyde could show a level of grit and depravity and violence that made Film Noir feel tame by comparison.

So where does one begin? If you’re a Film Noir novice, here are our top 7 films to whet your appetite for a deeper dive into this wonderful, thoughtful and dramatic style of film making.

Some people call this Orson Welles gem, the last great Film Noir (at least from the classic time-period of the early 40’s to the mid 50’s). In many ways, this was the last of a dying breed, and it used many of the classic motifs with aplomb. The opening shot is a masterful long trucking shot that would make a film maker like Martin Scorsese proud. The contrast between light and shadow is stark in this film, but what’s great about it is that it doesn’t merely exist for its own sake. The harsh lighting was used effectively to reveal story moments and to create a level of discomfort in the mood of the audience in key scenes. Although the film lacks the femme fatale motif, it effectively uses the motif of crooked police officers using their power to help corrupt the overall systems. With its depictions of drug use and willingness to show violent acts that hadn’t been seen on screen before, A Touch of Evil acts as a bridge between the classic Film Noir and the more realistic and violent and edgier films that were only a decade or so away.

Another Film Noir starring Orson Welles, but directed by Carol Reed, this film explores the ideas of loyalty and relies heavily on German expressionistic lighting, as well as the use of “Dutch Angles” by cinematographer Robert Krasker. This is another film that uses hard contrasts between light and shadow to effectively advance the story and set the mood. Taking place in post-war Vienna, it has a European grit that made this film look unique among other Film Noir. Also, the climactic chase scene is tense and beautifully shot, the dialogue is biting and curt, and the overall story is riveting and borders on heartbreaking.

Film Noir always has an undercurrent of sexual tension, but John Garfield and Lana Turner couldn’t help but bring that sexual tension to the forefront in this psychological thriller based on the novel by James M. Cain. This is a story about infidelity and how the consequences for your actions will always catch up with you (and often in tragic ways that you won’t expect). There isn’t a ton of German expressionist contrast in light and shadow in this film, at least that’s visible on camera. The contrast between light and dark lies solely in the characters and their actions and their desires. Foreshadowing in the script leads to moments of palpable tension and events that are planted early in the story are paid off in tragic ways.

Possibly the least Noir film on the list, Mildred Pierce still has many classic Noir components. Directed by Michael Curtiz (Casablanca), Mildred Pierce follows the title character as she believes she’s setting herself up for a lifetime of success after leaving her husband, but is actually slowly and methodically heading for disaster. Many Film Noir films involve the self-destruction of the main character and Joan Crawford delivers a performance for the ages as a woman trying to make it in a man’s world, but is constantly betrayed by the very men she should be relying upon. In an interesting flipping of the script, it is Mildred who inches towards self-destruction at the hands of male fatales, although there is one notable femme fatale in this film, and her revelation will break your heart.

Perhaps the prototypical detective movie, John Huston directed Humphrey Bogart as Sam Spade, the jaded private detective who finds himself on the trail of a legendary treasure that may or may not exist. With a gaggle of nefarious characters and an adequate femme fatale, Sam Spade turns out to be one of the few Noir protagonists to avoid the pitfalls that other men so easily fall into. As the mystery unravels, the story takes us to some dark places, but shows us that it’s possible to come out okay in the end.

2. Out of the Past (1947)

Robert Mitchum stars in this film as Jeff, a simple filling station owner with a dark past that he would love to leave behind him. The problem is that a chance meeting leads him back to a gangster named Whitt (Kirk Douglas), who he betrayed years ago for the love of femme fatale Kathy (Jane Greer). She had betrayed him by shooting his partner down in cold blood. This all creates an intricate web of a story that can only end one way. It’s about vindication and loyalty and ultimately doing the wrong thing as a means to the right ends. This is a deep and complex film that is filled with surprises right up to the very end.

1. Double Indemnity (1944)

Billy Wilder’s masterpiece that stars Fred MacMurray as the doomed insurance salesman Walter Neff, and Barbara Stanwyck as perhaps the greatest, most prototypical femme fatale in the history off Film Noir. It is not hyperbolic to say that every femme fatale must be compared to Stanwyck’s brilliant portrayal of Phyllis Deitrichson. She ensnares Walter into her web of deceit that leads Walter to kill Phyllis’s husband so that she can collect the insurance money. This film has all of the Noir components from the aforementioned doomed hero and femme fatale to the German expressionistic lighting to the simple motif of bad people doing bad things that end badly for them.

Indeed, Double Indemnity should be high on anyone’s list of classic Film Noir movies to see!

“Listen carefully! The pellet with the poison’s in the vessel with the pestle. The chalice from the palace has the brew that is true.”

Screenplay by Norman Panama & Melvin Frank