“What is your major malfunction, numbnuts? Didn’t mommy and daddy show you enough attention as a child?”

Screenplay by Stanley Kubrick, Michael Herr & Gustav Hasford

RIP R. Lee Ermey

“What is your major malfunction, numbnuts? Didn’t mommy and daddy show you enough attention as a child?”

Screenplay by Stanley Kubrick, Michael Herr & Gustav Hasford

RIP R. Lee Ermey

Asking whether the Academy should take box office numbers into account is a fair question, and one that came to my mind when I read the article linked here. I saw the article on my Facebook feed the other day, and the writer compared the last 15 Best Picture winners with the last 15 yearly box office champs through last year, and he discovered that only The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King was both Best Picture winner and box office champ. What’s more, since 1980, only three other films (Titanic, Forrest Gump & Rain Man) won Best picture and the box office title in the same year.

But is it fair to call the Academy “out of touch”, as the writer does, for not bestowing more Oscar love on films that do well at the box office? I guess it depends on how you look at it since naming one film the Best Picture of the year is a subjective matter of the highest order. Also, I would like to know if the writer thinks that the Box Office champ automatically deserves to be considered for Best Picture. If that’s the case, I think the premise is a bit misguided. Does the writer really think that The Hunger Games: Catching Fire was more deserving of winning Best Picture than 12 Years a Slave? Or that The Avengers should have won over Argo? How about Spider-man 3 beating No Country for Old Men?

There were three other times over the last 15 years when the box office champ was nominated for Best Picture with Toy Story 3, Avatar and American Sniper. Plus, films like Chicago, Million Dollar Baby, The Departed, Slumdog Millionaire, The King’s Speech, and Argo all made north of $100 dollars and were in the top-25 for box office during the years of their respective releases. While that isn’t a large sampling, it’s not as though the Academy has completely ignored films that did well at the box office.

As mentioned above, it’s clearly subjective, and always has been. Anyone who is familiar with this blog knows that the best movie of the year doesn’t necessarily win Best Picture. Hell, sometimes the best movie of the year doesn’t even get nominated. But should the Academy consider a film’s box office prowess, or lack thereof, when determining whether it deserved to be nominated or to win? I contend that the answer is no.

If the award was Most Popular Picture, then the obvious answer would be yes. But as anyone who has ever seen bell bottom pants during the 70’s can attest, just because something is popular doesn’t mean that it’s good.

The obvious answer is that the film has to have mass appeal. How does it get that mass appeal? It usually accomplishes that by appealing to the lowest common denominator. You have to make a movie that is flashy and entertaining so that it attract eyeballs. You also have to know demographics and understand that people under 30 are the people spending the most money at movie theaters, so the movies have to appeal to a, say, less mature movie-going audience. Most of the box office champs over the past 15 years have been action movies, like the Marvel movies, three different Star Wars films The Return of the King, Avatar and even American Sniper had an element of action to it, even though it was primarily a drama. What most of the action films have in common is that they’re popcorn movies. They’re movies that you go and see for their shear entertainment value, and that’s about it. While these films are wildly entertaining, they often lack the substance of a film that you think of when you think of a Best Picture winner. They’re fun, but they’re shallow.

![]()

The perfect example to me is the year that The Hurt Locker beat Avatar. The latter went on to become not only that year’s box office champ, but the number one box office movie of all time, until it was beaten, domestically at least, by Star Wars: The Force Awakens, another box office champ that wasn’t even nominated. Avatar is a film that pushed the limits of technological film making with its stunning use of motion capture, 3D stereo and CG animation and environments. The storyline was filled with impossible action sequences that kept audiences entertained and engaged. It was easily the most entertaining film of the year. However, it had a storyline that was not much more than a mashup of Dances With Wolves, Pocahontas and a dash of The Matrix. That made the plot predictable and not particularly engaging. Many of the details of the story (hello, unobtainium) were laughable. The characters were little more than cut out caricatures of archetypes that felt like movie characters and not like real people (or aliens) with whom we could form an emotional attachment. It was a production that was second to none, and was like going on a thrill ride, but was emotionally wanting.

The Hurt Locker, on the other hand, was slow with intermittent action that was done intentionally to mimic the reality of the lives of the soldiers in Baghdad. The action scenes were not fast paced adventure fare, but were tension filled moments where little was going on, but the whole world could have literally blown up at any moment. In this film we did have characters that, although they were in extraordinary circumstances, were characters with whom we could relate and root for. They were real people put in extraordinary situations that many people had strong feelings about. The Hurt Locker required a level of introspection and reflection that Avatar with all of its flash and dazzle could not duplicate. It is the emotion factor that separates the good films from the great.

Think about the list again and think about which films elicited greater emotional responses. In almost every circumstance, it would have been the dramatic Best Picture winner over the action adventure box office champ. Out of the 14 years where the box office champ didn’t win Best Picture, I generously count three times where the box office champ emotionally measured up equally or favorably to the Best Picture winner: American Sniper vs. Birdman; Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 2 vs. The Artist and Toy Story 3 vs. The King’s Speech, but the latter is closer than you might think. In all of the other examples, the Best Picture winner was far and away the more emotionally engaging film as well as the more thoughtful film.

Ultimately, I think that’s the point that the writer of the attached article missed. There’s nothing necessarily wrong with Spider-man 3 or Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith… well, yes there is, but my point is that while most of the action films on this list are fun and entertaining, the only one that really hit any kind of emotional chord was The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, and guess what; that’s the one that won.

If you’re interested in exploring more of my thoughts on Best Picture winners, I spent a year and a half watching and reviewing every film that ever won that award. Those posts can be found here.

“Today I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the Earth.”

Screenplay by Jo Swerling & Herman J. Menkiewicz

Original quote by Lou Gehrig

“He’s not the messiah. He’s a very naughty boy!”

Screenplay by Graham Chapman, John Cleese, Terry Gilliam, Eric Idle, Terry Jones, & Michael Palin

“Sometimes you’re so beautiful it just gags me.”

Screenplay by Robert Riskin

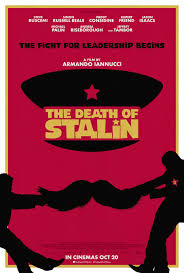

If you didn’t see The Death of Stalin when it opened in theaters this past weekend, and judging by the box office numbers, you didn’t, then you missed a biting satire with a script that performs dialogue gymnastics and a troupe of actors who brought their A-games to the screen. This is a thoughtful and funny film that might not be for everyone, but if you like satire and thoughtful humor, this is a film for you.

The film opens during the final days of Stalin’s reign as Secretary General of the Soviet Union. His death marks the end of the first Act, and launches the rest of the characters on the adventure of who will succeed him. It is more of a misadventure, really, as the chaos created by this team of rivals trying to one-up each other without being killed by each other creates dramatic irony and humor that you’re almost ashamed to laugh at. In fact, that is the risk that director Armando Iannucci took in making this film. Josef Stalin could lay claim to being the most brutal dictator of the 20th Century. He had as many as 20 million people killed, countless more sent to gulags, and the lucky ones were exiled. A generation of Russians, Georgians, Lithuanians, Ukrainians, etc. lived in abject fear that they and their family could be rounded up and shot for the most banal of missteps, and Iannucci took that fear and created comic gold from it.

It could be that since Stalin died more than 60 years ago, and the Cold War fires he helped to stoke have themselves been extinguished for a generation, that allows for this genocide to be looked at through the prism of comedy without feeling that its seriousness is being diminished. In fact, when it’s done effectively, comedy can be more biting in its critique, more effective at showing the folly of those involved, and more unforgiving in pointing out their fallacies, than even the heaviest of dramas. What comedy is able to do more effectively than serious drama is to point out the absurdity of any situation, and few 20th Century ideals were more absurd than Soviet-style communism.

The Death of Stalin reminds those if us of a certain age who remember the Soviet Union and the ideals that kept it moving, will appreciate this film on a level that younger audience members might not be able to relate to. There are several jokes about not being able to act on even the simplest of ideas without having a committee meeting. The plot that drives the film is the absurdity in the transition of power. Since Stalin ruled over the Soviet Union with an iron fist, there was no plan of succession, and the people left behind had to sort it out in a way in which they were not entirely capable, and the film shows that incompetence to hilarious effect. Finally, once the power is sorted, we’re told that, even though Khrushchev would lead the Soviet Union for a decade, his hold on power was tenuous at best, and he would ultimately lose it to someone younger, hungrier and more ruthless than he.

There are two moments in the film that stood out to me in showing just how absurd the whole situation was. Overall, Iannucci did an outstanding job in general of showing the fear and paranoia in which the average citizens lived. It’s easy to forget in the world we live in today that such a world existed where you couldn’t even speak ill of the nation’s leadership in your own home for fear of your own children turning you in, but we see it clearly displayed here. Even after Stalin is dead, there is an underlying fear that everyone has that they’re acting in ways in which he would not approve. Even in death, Stalin casts a shadow over every character in the film that they can’t get out from under. However, these two specific moments are perhaps the funniest moments in the film, and clearly show just how unprepared these men were for the grave responsibility that befell them.

First, just after Stalin has died, his daughter Svetlana (Andrea Riseborough) arrives. The surviving members of the board, Khrushchev (Steve Buschemi), Molotov (Michael Palin), Malenkov (Jeffrey Tambor) and Beria (Simon Russell Beale) are already starting to try and position themselves for the top position. Within this group factions form and they individually try to curry favor with Svetlana in order to acquire any advantage that they can. During the climax of the scene when they finally decide to drive back to Moscow, a traffic jam occurs in the drive way as each tries to jocky himself into the position immediately behind Svetlana’s car. This is a signature moment in what makes comedy so great. Four people want the same thing and they want it badly. The absurdity in the moment is thinking that having a car closer to the front of the line will somehow give them an advantage, and yet they their hardest to accomplish something that any reasonable person knows means nothing until they’re on their way and Krushchev is left lamenting the fact that he’s in the back of the line.

The other moment is when the whole board is together in a meeting room discussing the funeral and how other problems around Stalin’s death will be managed, and Molotov gives what might be one of the great verbal gymnastics performances of all time. Compound his going back and forth with the other members of the board not knowing whether to raise or lower their hands depending on however Molotov concludes his point and each sentence contradicting the one that came before it, and you have another side splittingly hilarious scene that has its humor derived from its absurdity. A point of order ought to be mentioned here in that I am a fan of Monty Python, and, while there are Pythonic elements in this film, one wouldn’t mistake it for Monty Python. However, in this scene, Palin hearkens back to those halcyon Python days with a performance that would have any Monty Python fan falling out of his or her chair in laughter.

Similarly to the best of Monty Python, The Death of Stalin is a thinking person’s comedy. It’s a thoughtful film that will challenge the viewer in a way that modern films don’t often do. While I would stop just short of calling it a great film, I would still call it a very good film that I would recommend to anyone who is willing to put in the effort of seeing it. This isn’t a film that you can watch passively. You need to engage with this film. Fortunately the actors in it all give virtuoso performances, so that you can engage with the characters on an emotional level. Iannucci also made the interesting creative choice to be deliberate in his portrayal of the carnage of Stalin’s regime. There are some moments of graphic violence, but most of the atrocities happen off camera and out of sight, which is very symbolic of how they happened in reality. Not many people outside the Soviet Union knew what was happening at the time, and those inside the Soviet Union had to look the other way for their own self-preservation.

Overall, this is a film that is worthy of your time. It might be hard to find it in a theater, but you should endeavor to do so. These types of films need to be supported. With Black Panther having crossed the $1 billion mark, and more fair from Marvel and Star Wars and other ginormous franchises on the way, maybe we could take a break from seeing them again for a moment, and go see a film that isn’t flashy, isn’t a spectacle, but is no less cinematic and no less entertaining. You might surprise yourself and remember that there are still mid-level movies that provide theater-quality entertainment.

Chalk one up for the Fantasy genre. The Shape of Water joined The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King as the only true Fantasy films to win the Oscars’ highest honor. A modern-day fairy tale, The Shape of Water actually seems like a polarizing winner, as many people liked it, but not a ton of people, other than critics, loved it. This may speak to the quality of the films nominated this year, and there will be more on that in a bit, but it seemed, anecdotally anyway, that there was not a huge consensus on what 2017’s best picture was. Many people loved Lady Bird. There was a lot of sentiment for Get Out, and Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri and The Post were clearly the kind of Oscar bait that usually get rewarded for being such. However, as the season rolled on, it was clear that momentum was on the side of The Shape of Water, and that momentum was confirmed on Oscar night.

I will start out by saying that I am a casual fan of Guillermo del Toro. I loved Pan’s Labyrinth. I liked Hellboy. I thought Pacific Rim was a fun, though insanely flawed film. I went in to The Shape of Water with high, though somewhat tempered hopes. I had heard a bit about the subject matter, so I knew that I had to go in with that willing suspension of disbelief that doesn’t fit very well in today’s cynical world. I came out the other side appreciating what it tried to do, understanding that this was a fairy tale and needed to be considered as such when evaluating it, and still feeling underwhelmed.

Even though the tones of the two films are completely different, I think del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth comes closest in style to what The Shape of Water is and what it’s trying to attempt. Even though Pan’s Labyrinth is a much darker story, they both have an element of whimsy that is quite often missing from films like this. Both films use Doug Jones in monster costumes, both films use haunting narration to set up their respective scenarios and both films use muted color palettes that make them almost feel like black and white movies. And there were many motifs throughout The Shape of Water that were reminiscent of Pan’s Labyrinth from the monsters, both literal and figurative, to the bloody wounding of men’s cheeks, it would be clear to even the novice film goer that these films were directed by the same person.

Where Pan’s Labyrinth was more successful from a storytelling standpoint was in creating emotion. For as dark as Pan’s Labyrinth is, you have an emotional attachment for everyone in that film, and del Toro was fearless in the places he would go in order to get extreme emotional reactions from the audience. It’s possible to make emotional connections with the characters in The Shape of Water, but they’re not nearly as intense as they are in Pan’s Labyrinth. That is where my own issues start with this film. I like all the characters I’m supposed to like, and I dislike the characters I’m supposed to dislike, but I don’t necessarily care about any of them.

Elisa (Sally Hawkins) is the heroine of this film, and she is everything that you would want in a main character. She is precocious and proactive. She has weaknesses and flaws that she has to overcome, but she also uses to her advantage. She is a character with depth, and she’s likable. But she’s a little strange, and call it what you will, but that quirkiness makes it difficult to relate to her. Ofelia from Pan’s Labyrinth had many of the same qualities and quirks, and she was living through extremely difficult circumstances that few people alive today could relate to, but something made her much more relatable as a character. It could be that she was a young girl, and such whimsy is more acceptable from a child rather than from a grown woman, and the whimsical nature of her adventure stood in sharp contrast to the dangerous and depressing world in which she was living. Elisa is a part of her world, but because she’s mute, she’s been to this point in her life more of an observer than a participant. Attempting to rescue this creature with which she’s formed this bond not only allows her to feel like a participant for the first time, but it also has allowed her to make a real emotional connection with another sentient being, the type of which she’s never had with any human being. That, I believe, is the underlying point and theme of this film. It’s about love, and it’s about being an active participant in your world.

On the flip side of this coin, we have the antagonist, Richard Strickland (Michael Shannon), a bigoted government agent who is responsible for the capture of Amphibian Man, and wants to turn him over to the military. Del Toro and co-screenwriter Vanessa Taylor did a terrific job of giving Strickland depth by giving him the appearance of being a family man, although for the most part he neglects his kids and mistreats his wife. He is the clear monster in this monster movie, and he shows us that sometimes monsters can wear suits. This is again a similar motif to Pan’s Labyrinth. The monster in that movie wore a uniform in the person of Ofelia’s step father, Captain Vidal, the sadistic soldier of Franco’s Fascist army, who abuses Ofelia and her mother and is more concerned about leaving a macho legacy for his unborn son than he is showing love to any living person in this story. Both of these villains are effective monsters, but Vidal has a lot more menace than Strickland, who is an effective villain, but del Toro wasn’t able to give him the same cold-blooded ruthlessness of Vidal, and that lessens this story.

I think that’s where the difference comes in between these two pictures, and why The Shape of Water didn’t resonate with people as much as it could have. We never feel like Elisa is in danger until the very end of the story. She’s always one step ahead of Strickland, and we’re never worried that Strickland will catch on. And even if he does, he’ll take away Amphibian Man, but it doesn’t feel like Elisa is in danger of anything bad happening to her. Contrarily, in Pan’s Labyrinth, Ofelia is constantly in danger. Whether it’s from Vidal or the various challenges that Fauno presents to her, we’re constantly on the edge with Ofelia, and that suspense heightens the emotional connection that we have with the character. Since we never really reach that height with Elisa, we never make the connection, and thus, don’t enjoy the movie as much.

I think that the other problem is that most people just can’t get past the fact that Elisa has sex with a sea monster. From a mythic standpoint, this isn’t a new thing. Mythology from all cultures are littered with stories of humans having sex with gods, with animals, or any other manner of being. The fact that Elisa probably comes from the water herself isn’t enough to bridge the gap for today’s average movie goer. There’s an interesting line in the film when Giles (Richard Jenkins) is talking to Amphibian Man, and he wonders if he was born too early or too late. The ironic thing is that this film suffers from the same conundrum. Even though it won Best Picture, it’s not a film of this time. It’s either a film of an earlier time when we weren’t so cynical or it’s a film of a later time when we’re more open minded to different kinds of thematic exploration. This is a film that is both too early and too late for its time.

Is The Shape of Water a bad film? Not in the least. In fact, there is much about it that is enjoyable. Octavia Spencer, playing Zelda Fuller, Elisa’s best friend and archetypal mentor, brings her typical wry wit that adds an element of humor that is atypical for a del Toro film. In fact, all of the performances were terrific, and Spencer (Actress in a Supporting Role), Jenkins (Actor in a Supporting Role) and Hawkins (Actress in a Leading Role) were all nominated for Oscars for their respective performances. This is also a beautiful film to look at, as its Oscar win for Best Production Design demonstrates. So while this isn’t your typical Best Picture winner, it’s not a crime that it took home the statue.

Did the Academy get it right?

No, they did not. While it might not be a crime that it won, it still wasn’t the correct decision. Get Out was a game-changing type of film that had a cultural impact that far exceeded any of the other nominees, and really should have been named Best Picture. Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri was also a better and more emotionally engaging film than The Shape of Water. Lady Bird was another film that struck a chord with a lot of people for its candid views of the relationships between mothers and daughters, as well as its coming of age motifs. Phantom Thread was another haunting film that left some people scratching their heads with its somewhat ambiguous ending. Christopher Nolan’s Dunkirk put us on the beach and in the middle of the seminal battle that, even though it ended in allied retreat, saved the British military to fight another day, and it was riveting and suspenseful to watch. On the flip side of that was The Darkest Hour, a film about Winston Churchill, and the political side to Dunkirk, and how Churchill risked everything in encouraging going to war because he knew that appeasement with the Nazis would be a failed policy. Any one of those films could have made a compelling case for Best Picture. The only one that I leave out was Call Me by You Name, which, while beautiful to look at, was an undramatic look at a teenager coming to grips with his sexuality and falling for a man in his twenties who ends up taking advantage of him. It was a bit too nuanced for me, and not up to the standards of the other nominated films. The rest of the films were that close to each other. There was no clear cut favorite. To be honest, my two favorite films of the year weren’t even nominated, but I could make a strong case that either Baby Driver or I, Tanya was really the best film of the year.

Should you see it?

Here’s the thing. If you haven’t seen The Shape of Water already, and you take advantage of an opportunity to see it, do this: go into it with the understanding that you’re going to be watching a modern-day fairy tale. This film requires an abnormally large willing suspension of disbelief and a wide open mind for any possibility in order to fully enjoy the subtleties of this magical story. It really is a wonderful film in its own way. Should it have been named Best Picture? Probably not. Is it worth two hours of your life to sit and watch it? Probably yes.

“If I told you about her, what would I say? I wonder.”

Screenplay by Guillermo del Toro & Vanessa Taylor

“My friends. You bow to no one.”

Screenplay by Fran Walsh, Philippa Boyens & Peter Jackson

“The list is an absolute good. The list is life.

Screenplay by Steven Zaillian