Anyone who has spent any time around my blog knows that I am an advocate for proper dramatic structure in a screenplay. This is especially true if you’re an unknown talent trying to break into the industry. Agents and executives are going to first want to know that you know the rules before they’ll trust you to properly break them. But there is a different and less arbitrary reason for making sure that your script is properly structured. That reason is that the script will just be better. You will have a better sense of the story while you’re writing it. Your characters will have clearly defined goals and needs, which will more actively engage the audience. And most importantly, the narrative will have a natural flow, which will turn your plot into a story.

As I like to say, plot is what happens. Story is why we care.

That was a title of a recent blog post and you can read that one here. I’m harping on this because I’ve been reading a lot of scripts lately and almost to a man, the most common problem with all of them is that they either have no structure at all, or they have structure that is incomplete. The most common mistake is that there’s a clear break between Act I and II, but no break between Act II and III. The reason for that is often because the writer didn’t give the hero a clear flaw that caused her to hit a low point and lose everything then have to grow and change in order to truly win in the third act. A story feels incomplete if it doesn’t have an ending. All scripts end, but not all of them have endings.

With that in mind, here are four reasons why your script needs a strong dramatic structure.

It defines your hero’s progress through the story

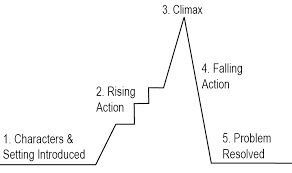

How many times have you been watching a movie and you start realizing that the story isn’t going anywhere? There are things happening, but it doesn’t seem like there’s going to be an end to any of these means. The reason for that is probably because the hero doesn’t have a clearly defined goal, or even worse, there’s no clearly defined hero in the script. Doing a fusion of the Hero’s Journey as adapted by Christopher Vogler and Syd Field’s 3-act structure notion, along with my own thoughts on how the best scripts are told in four acts, look at the various stages of where a character should be in relation to the story. Act I is the Ordinary World and is generally where the hero gets her Call to Adventure. The hero’s world, which had been in balance until some inciting incident knocks it out of balance, must decide whether or not to do whatever needs to be done to get her world back into balance.

Act II begins when the hero Crosses the First Threshold into the Special World of the adventure. Most people get this right and generally get it to happen in the correct point of the script. It’s what happens after it that messes people up. The first half of the second act is a series of tests for the hero to go through, and that culminates with a midpoint of the story where the hero experiences the biggest test to date. Quite often, this is where the hero attains the initial goal. Indiana Jones finds the Ark of the Covenant. Luke Skywalker rescues Princess Leia. There are many examples of this, and the second half of Act II is generally the repercussions of that. Indiana Jones now needs to keep the Ark out of the hands of the Nazis. Luke and Leia have to get the Death Star plans to the rebels. Then Act III begins, usually with the failure of the hero to accomplish what he needed to in Act II. The Nazis get the Ark. Luke and Leia didn’t get the Death Star plans to the rebels in time and now the Death Star is threatening to destroy them.

Then in Act III, the hero overcomes that failure based on new things that she’s learned and she restores balance to her world, even though it will never be the same (for good or for bad) as it was before.

The consistent thing about that breakdown, was that in those examples, we know where the hero is in the story. We know that he’s working towards accomplishing his goals, and there is dramatic tension as the forces that are against him are trying to stop him.

It creates better pacing and flow

What the above outline also does is it creates pacing and flow to the story. The natural flow of dramatic story structure, and particularly the Hero’s Journey, allows for ebbs and flows in the pacing so that there are moments of excitement and tension followed by moments where the story slows down so the audience can catch their breath.

When a story lacks structure, it also lacks pacing. The structure provides a clearly marked path for the story to follow, and without that path, the story merely meanders through a roughly defined plot. Audiences can sense this and will likely tune out if the story is too fast or too slow. Think about action movies where the plot is simply what happens between explosions. There’s little pacing to that type of scenario. It’s a fun ride, but often not a satisfying story.

It allows the story to have an arc

Piggybacking on the first two reasons is story arc. This can mean several things, but generally it has to do with the various moods that the story puts you in or the internal thoughts that it inspires. It can be understanding the flow of the story what the hero needs to do to keep the story moving. Whatever it is, you can’t hang an arc on a story that has no structure because without structure, there’s no place to put an arc. Without that arc, it won’t feel like the story is going anywhere, and the feeling for the audience will get pretty stale in short order.

It accentuates the story’s thematic components

Finally, every good story, and I don’t care what genre it is, has strong thematic components. I don’t care if it’s action, comedy, horror, western, drama, or science fiction. If it has a good story, that means there are thematic components behind it. Generally, the theme is the lesson or moral or idea that they storyteller is trying to get across. A good story structure paces what the writer is trying to say in a way that reveals information and ideas at the proper moments in the story. Without that structure, the story is nothing more than a pool of ideas and there is nowhere to thoughtfully place ideas for people to consider, even subconsciously as they watch the film. There’s just a whole lot of nothing there.

At Monument Script Services, we pride ourselves on being experts at evaluating story structure, pointing out where it could be better and offering up solutions for improvement. If you have a script that you believe has a good story, but just can’t quite fit it in to the proper dramatic structure, we can help. Click here to see the different services we provide, and let us know which one would be best for you.