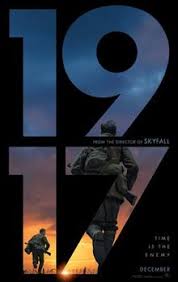

There is a reason 1917 is crushing it at the Box Office. Yes, it’s one of the most intense films I’ve seen in a long time. It almost never lets up. Even scenes in which the action and the tension seem to lessen in order for the audience to catch their collective breath, there is still an underlying feeling of tension that danger is never far away. Perhaps it’s around the next corner. Perhaps it’s on the other side of a closed door. Perhaps it’s waiting in the very room they’re in. Just as in a real war setting, you never know when that fatal bullet will strike, when the death blow will be dealt. But what is really propelling the popularity of this film is that it tells a compelling story with which the audience can engage.

With this film, Director and co-screenwriter Sam Mendes is cementing himself as one of the great story tellers of his generation. Indeed, everything about 1917 is superb. The acting is at once subtle and dynamic. Director of Photography Roger Deakins is at his light painting best. Mendes own direction runs at a pace that feels impossible to keep up, but does so in ways that are riveting and emotional. It was also impressively shot in a way that made the whole film feel like one continuous shot, similarly to Birdman. The screenplay, co written by Mendes and Krysty Wilson-Cairns, shows way more than it tells, which is exactly what you want from a screenplay. It might not be hyperbolic to feel that this film is something close to a masterpiece.

One thing I also noticed while watching the film was how strong of a Hero’s Journey it had and how archetypal the storytelling was. It would have been easy for Mendes to have turned this into a simple and forgettable action movie like 2014’s Fury, but instead we got a carefully crafted, thematically strong story with an anti-war message that was subtle and subdued, and didn’t disparage the warriors.

The emotion stayed just under the surface. It was always ready to explode, but the men, like the men of that generation, kept it stifled, for fear of showing weakness. They should have been robots, but somehow this subtle showing of emotion, this overt stifling of emotion, created a much more gut wrenching emotional situation. There are two moments in the film where characters briefly allow their emotions to get the better of them, and then immediately stifle them. This stifling of emotion makes the audience feel even more sympathy for these characters because they’re surrounded by death and heartbreak, but they must appear outwardly strong, not only in the face of the enemy, but in the faces of their own.

And that speaks to the duality and depth of this film. The main characters are on a mission to prevent an attack from happening. This would normally be antipathy to a war story, but the goal of the characters in this story is not to defeat the enemy, but to prevent a scenario that would lead to their own ultimate defeat. That means having patience and prudence and the strength to show restraint. A WWI film from the 50’s called Paths of Glory, directed by Stanley Kubrick, showed the consequences of seemingly showing cowardice in front of the enemy, and talking yourself into attacking against overwhelming odds. The anti-war message in Paths of Glory showed the folly of war through the pompous arrogance of the generals and how their rash decisions cause their subordinates to suffer. Ultimately in Paths of Glory, characters were punished for failing to attempt that impossible assault. In 1917, the main goal of the main characters was to prevent that impossible assault from happening in the first place, as the generals are trying to prevent one of their own subordinates from rushing blindly into a rash assault.

That component on the story creates an anti-war theme that’s caught within the subtext of the premise rather than being preached to us throughout the narrative. The premise is that English army intelligence has discovered that a battalion of troops is walking into a trap, and two young soldiers need to cross the front lines in order to get that information to them to save them from a slaughter. Oh, by the way, one of the two soldiers also has a brother in that battalion.

One thing that can’t be overstated is the strength of the screenplay. Anyone who has followed this blog with any amount of regularity knows that I am an advocate of the 4-act structure in a screenplay, and the screenplay for 1917 has that. Unfortunately doing an act-by-act breakdown will reveal spoilers, and this is a film where I particularly don’t want to do that. Aside from the structure, one of the strengths of the screenplay is that important things happen throughout the story and those events all heighten the drama. Knowing about them ahead is time would lessen your enjoyment of the film, so perhaps this script breakdown will come sometime in the future.

Another thing that you know if you follow this blog is that I am a disciple of The Hero’s Journey. Again, I don’t want to do a full on Hero’s Journey breakdown because I don’t want to give out any spoilers since the movie just came out, but suffice it to say, 1917 has a complete and compelling Hero’s Journey. One thing I can say about it is that it’s not a traditional Hero’s Journey. All of the stages are there, but some of them happen in an nontraditional order. For example, the Meeting of the Mentor stage actually happens throughout the story, as different Mentors guide our hero along his journey. Some are traditional mentors and others are more unique in the lessons they teach him, but the journey has several mentors right up to the very end that teach the hero as well as the audience about the world of the story.

That leads me to another point. This is essentially a road movie. Yet another thing that you will know if you follow this blog is that I am not a fan of road movies. I feel they tend to be episodic and the episodes rarely build the drama. Rather, they’re often vignettes that don’t build on each other and you can change the order of then around and it would have no affect on the story. These films often lack the spine or through-line that builds a narrative. In 1917, however, the road that the main characters go on is the through-line. Each stop they make leads to the next one, and each stop has something happen in it that pushes the narrative forward, and each stop has an affect on something that happens later or happened earlier in the story.

Another point that needs to be expanded on is the paucity of dialogue, especially in the second half of the film. There is some small talk between the soldiers as traveling friends will take part in. There are examples of witty banter and there is some exposition through dialogue, mostly in the first act. But once we get to Act IIB, there’s almost no dialogue with the exception of a couple of key scenes. The story telling is almost entirely visual at that point, and it couldn’t be more riveting or intense.

What’s more, the screenplay works in tandem with Roger Deakins’ superb cinematography to tell a compelling story. As I said earlier, no one paints with light like Deakins, and there is a scene with night flares and shadows where we come in and out of darkness. In this scene, however, darkness means safety and light means danger. If you can be seen in the light, you can be shot. The darkness offers cover and it’s one of the few times in cinematic history that I can remember rooting for darkness.

Overall, what makes a film like 1917 so refreshing and such a breath of fresh air is the story telling. It’s a war movie without an overt amount of special effects. It doesn’t have a ton of traditional action sequences, so when an action sequence does come around it feel that much more intense. Plus, the action scenes build in intensity as the film presses on. This is a textbook example of terrific storytelling and any aspiring screenwriter should study it in order to hone their own craft.