“The D is silent.”

Screenplay by Quentin Tarantino

“The D is silent.”

Screenplay by Quentin Tarantino

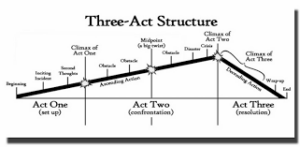

I have been reading a lot of scripts lately that have a lot of depth but not the kind of depth you want in a screenplay. They have depths of problems that are all interrelated. They have decent plots, but the stories lack structure. They have likable characters but haven’t given them clear goals. These problems are interrelated because you can’t have a strong story structure in your screenplay, or any structure at all for that matter if your protagonist doesn’t have a clear goal.

Story structure is not just some arbitrary guideline that some guy in a big studio office demanded. It is not a random rule for screenwriters to follow, only to give executives a reason to pass on a script if it doesn’t. The structure of a screenplay has a significant and important purpose in the telling of a story. It marks the protagonist’s progress toward achieving her goal.

The first main plot point is the inciting incident that calls the hero to action. The next plot point is the transition from Act I to Act II when the hero Crosses the First Threshold, leaving behind the Ordinary World of her past life and committing to the Special World of the adventure where she will attempt to accomplish whatever goal she has been called to accomplish. The next plot point is the twist in the middle of Act II that divides Act II in half and forces the hero to recommit to the adventure in a way she hadn’t been previously prepared for. The next plot point transitions us from Act II to Act III and is often referred to as the “all is lost” moment. This is when the hero, usually because she hasn’t overcome some internal flaw or wound or has some inner need that hasn’t been addressed, loses everything and appears to have lost out on the chance to accomplish her goal. The final plot point is the climax, the final challenge for the here in which she finally does (or doesn’t) accomplish the goal she was called to accomplish at the beginning of the story.

These are not arbitrary requirements. These are integral components to the telling of an effective, dramatic story. Without these moments, you might have a plot, but you don’t have a story. I often tell screenwriters after reading their screenplays that the plot is what happens, but the story is why we care. If you have a plot that no one cares about, then you don’t have a story.

This might come across as Screenwriting 101, but you would be surprised how many screenplays I’ve read recently in which the protagonist has no clear outer goal. What should also be mentioned is that there should be an inner need that conflicts with that outer goal. That is how you get character depth, and that is another great way to build drama.

The point is, however, that without that outer goal, it’s impossible to track the hero’s progress toward it. If the hero has no goal, there can be no story structure. The two of them go hand in hand. You have both, or you have neither.

So, if you feel like you’re banging your head on the wall because you can’t get the screenplay structure as tight as you want it, double-check your protagonist. Does she have a clear and well-defined goal, and has the story been built to demonstrate her progress toward achieving it? That is how the story should flow. It gives you good pacing, and it helps you build drama. Most importantly, when a story is structured properly, it allows the screenwriter to tap the maximum amount of creativity to create the best story possible.

I saw a couple of movies this weekend that I liked but didn’t love. Woman of the Hour is the directorial debut of Anna Kendrick, who also starred in the film. It’s airing on Netflix, and I have a lot of mixed feelings about Netflix movies in general. I don’t generally go out of my way to see them, and when I do see them, they’re generally just kind of meh. The other movie I saw was Here, which reunites director Robert Zemeckis with stars Tom Hanks and Robin Wright for the first time since Forrest Gump.

I enjoyed Woman of the Hour, but I didn’t love it. That said, I think it was an impressive first effort for Kendrick’s directorial debut. The storyline was a bit scattered and was kind of about something else other than what it was advertised as. It was advertised as a movie about a struggling actress who appears on The Dating Game in the late seventies, and the man she chooses has a dark past. What it was really about was that man, who was a real-life serial killer who potentially killed dozens of women. The bit about being on The Dating Game, while a major subplot, was just that, a subplot.

I did appreciate the acting performances in the film. Kendirck’s role as the struggling actress Sheryl Bradshaw showed her perkiness and her willingness to be subversive. Daniel Zovatto’s performance as the serial killer, Rodney Alcala, was subtle and sinister, often teetering on the edge of a cliff before finally jumping off. The main issue with the movie was that the storyline was disjointed. It went back and forth in time, making it difficult to keep up with, and there were too many characters who were only peripherally involved in the narrative and whose deals in the story weren’t sufficiently paid off, making their time in the story wasted.

I would like to see Kendrick direct more films. She has a voice that needs to be heard, and with more experience, she could become a fine director. This is a decent debut, but hopefully, she can improve on this effort next time. If you have Netflix, it’s worth checking out, but don’t change any plans to watch it.

…but that was a low bar. About five or ten minutes into the movie, I thought to myself, “Oh, I am not going to like this.” But as the movie went on and we got to know the characters, I got pretty engaged. The movie largely takes place in the living room of one house or in the forest that it would later occupy. The camera doesn’t move until the very end of the film, making it a lot like watching a play. It made for an interesting watch and one that could potentially be off-putting to some people.

Thematically, it was very strong. There were a lot of things going on in this film that I was able to relate to. I believe this is a film for older viewers. Gen X-ers and Baby Boomers will be able to relate to this film a lot more intimately than Millennials or Gen Z-ers. This is a film about loss and losing time and what we give up over the course of a lifetime to simply get from one day to the next. This film was also disjointed and was more like watching a lot of vignettes, but I thought they were effective, and I was emotionally moved by the story and the characters.

Overall, it wasn’t a strong weekend of viewing, but I’m glad I saw each film. We’re in that weird period before Thanksgiving where you might watch something that is clearly Oscar bait, or you might get stuck with something that’s just being dumped by the end of the year. While I didn’t get that feeling from either of these films, I wasn’t blown away by either of them either… either.

For more in-depth thoughts on both these films, check out the Gen X v Z: A Movie Podcast, available wherever you listen to podcasts.

“Forty years at sea. A war at sea. A war with no battles. No monuments. Only casualties.”

Screenplay by Larry Ferguson & Donald Stewart

Yes, we are early in Oscar season, but IMHO, we already have a front-runner. Conclave might be everything you look for in Oscar bait, but it is an exceptional piece of cinema. There is not a weak link in this film. The story is riveting. The characters are engaging. The cinematography is stunning. The overall work is entertaining and thought-provoking. Oh, and there is a twist at the end that, if you’ll forgive the hyperbole, might restore your faith in humanity.

Screenwriter Peter Straughan gave us a magnificent adaptation of Robert Harris’s novel. The screenplay is nothing less than a parable for today, not only with our own government but with governments around the world. Reactionary politicians are on the march in ways that jeopardize our freedom for some perceived security against the “other,” whatever those “others” happen to be. Along the way, Americans, in particular, are losing sight of what once made us great. The same could be said about the conference of cardinals in Conclave, as a small group of men seek power for themselves over what should be better for all. They look longingly at the past instead of boldly into the future. But a few men, idealists though they may be, see a better future with leadership that is more sensitive and empathetic. Straughan drew a clear line in the sand over which way would be the best way for the Church and, parabolically, the best way for the United States.

Three decades ago, Ralph Fiennes’ acting performance carried The English Patient to a Best Picture win, but he did not win Best Actor, even though the only reason that film won Best Picture was because of his magnificent performance. Without seeing other Oscar contenders yet to come, I hope the Academy gives Fiennes a make-up call and bestows that award on him for this film. While Fiennes had plenty of great supporting help in The English Patient (Best Supporting Actress winner Juliette Binoche, Best Actress winner Kirsten Scott-Thomas, Willem Defoe, Colin Firth, and a host of several others), he has another amazing supporting cast in this film with Stanley Tucci, John Lithgow, and Isabella Rossellini, just to name a few. The acting from top to bottom in this film is wonderful and makes the film much more enjoyable.

Director Edward Berger (All Quiet on the Western Front) and director of photography Stephane Fontaine crafted a beautiful film that helps tell the story and set the mood through the visuals just as much as through the dialogue. There are scenes that are framed and lit to accomplish specific moods and points of view. There are shots where the characters are framed around borders that make them feel restricted. There are times when there is no color anywhere in the shot, portraying a mood of cool calculation. There are shots focusing on the pain of Lawrence (Fiennes) as he wrestles with his faith in God while simultaneously attempting to uphold the sanctity of the Church’s traditions. This is a truly beautiful movie.

This is a movie about resurrection—not the literal resurrection of Christ, per se, but the resurrection of faith. It is a political thriller with an ending that is hopeful and optimistic about the future. It takes a lot to get there. The film is loaded with drama and intrigue, but the ending is satisfying and hopeful.

For more thoughts on this film, check out my podcast, the Gen X v Z: A Movie Podcast, which is available wherever you get your podcasts.

“The power of Christ compels you!”

Screenplay by William Peter Blatty

Last weekend I saw We Live in Time, directed by John Crowley and starring Andrew Garfield as Tobias and Florence Pugh as Almut. This film, to me, is an example of an “almost great” movie. Crowley did a nice job directing the individual scenes. Garfield and Pugh had wonderful chemistry as a couple navigating their differences and her terminal illness while trying to maintain an air of normalcy for their young daughter. They also both gave stellar performances that could gain some recognition for both of them this coming awards season.

Unfortunately, Crowley couldn’t direct his way out of a couple of plot holes that took me out of the movie just enough to reduce the emotional impact it had on me at the end. I feel like this was a movie that should have had me with a ginormous lump in my throat by the end. Whether these ideas were in the original screenplay and got cut for the sake of running time, I don’t know. But I do know the film needed another couple of scenes to answer a couple of key questions.

What Crowley did do very well was always have the feeling of limited time hanging over the characters. Obviously, Almut has limited time to live as she battles stage 3 ovarian cancer. However, even the day-to-day things they deal with as they go through their lives always have time as a backdrop.

Where he missed the mark were some of the details. There were a couple of scenes in particular that were missing that I felt should have been there in order to tie things up better. Almut is a chef who is up-and-coming and encouraged by her peers to compete in a European chef contest. However, her doctors, concerned about her metastasizing cancer, want her to pull back. She tells Tobias that she won’t enter the contest, but she does anyway, and the final round is scheduled for the day they’re supposed to be married. Tobias finds all this out when Almut’s aggressive practice schedule causes her to miss picking up their daughter from school. She admits to Tobias that she’s doing this contest and that it conflicts with their wedding day. We then see Tobias tearfully throwing away the wedding invitations they had so carefully chosen together, which feels very much like a representation of the fracturing of a relationship.

Then, the next thing we see is Almut prepping for the contest, then going out to the floor where a cheering audience waits. A cheering audience that includes Tobias and their daughter enthusiastically holding up a sign and cheering Almut on. Personally, I found that very jarring, and I felt like at least two scenes needed to happen in between. Tobias needed to have some realization of why this was important to Almut. She spent the previous scene saying how much she needed this so that she could be remembered as something other than her daughter’s mother. We needed to see Tobias have that realization and come to understand that this was bigger than him. He then needed to say that to Almut, who then needed to give something to Tobias, perhaps marrying him in a local courthouse before the competition to make their union complete. It should have been important for them to be on equal terms here as they prepare to part ways.

There was one other thing that I thought could have brought a lot more drama to this screenplay. Their first big fight is a disagreement over kids. Tobias wants them, but Almut doesn’t. Then after discovering she has ovarian cancer, she has the option to have a full hysterectomy to lessen the chance of the cancer coming back. She opts not to do that, thinking that maybe she would like to have children someday, and then her cancer goes into remission. Then they have a baby, but the cancer comes back, this time in a much more serious way.

There was a great moment for Almut to blame Tobias for her cancer. Even if he didn’t pressure her into not doing the full hysterectomy, although that would also have been better, she could have had a line telling him that she wouldn’t have this cancer if he hadn’t wanted kids so bad. Something along those lines would have created a lot of conflict and tension that would have been a lot more engaging and dramatic. It would have been another challenge for them to overcome, which would have made the movie much more interesting.

Otherwise, I thought this was a terrific film. As love stories go, We Live in Time might be this generation’s Love Story without the iconically sappy line. However, the last scene, where they go skating and wave goodbye to each other, was a little on the nose. If you like a good love story, this is definitely a film you should check out.

You can also hear more thoughts on this on the Gen X v Z: A Movie Podcast, which is available wherever you listen to podcasts.

“The men who are dangerous are the ones who do want it.”

Screenplay by Peter Straughan

It’s been a while since I posted anything, and I need to get caught up before we move on to one of the most exciting times of the year, movie-wise. So here are roughly 100 words each on some recent releases.

Francis Ford Coppola’s passion project landed with a thud with audiences and critics. Coming on the heels of Kevin Costner’s costly fumble with Horizon: An America Saga, moviegoers should be rightly distrustful of filmmakers past their primes as 10-minute standing ovations at Cannes. Megalopolis had a non-sequitur screenplay with too many subplots that didn’t go anywhere. It had uninspired acting performances, except for Aubrey Plaza and Shia LeBeouf, neither of whom could salvage this movie wreck. And on top of all that, it didn’t even look that good. This film was a failure.

The latest effort from DreamWorks Animation proves yet again what an underrated animation studio they are. Director Chris Sanders (Lilo and Stitch, How to Train Your Dragon, The Croods) showed off his creative genius yet again with a film that’s thisclose to being a masterpiece. The Wild Robot is a great film loaded with heart, humor, some macabre wit, and stunning visuals. Not a great animated film. A great film. This fish-out-of-water story has strong thematic components about belonging, overcoming obstacles, and the challenges (and rewards) of parenting. The emotion quotient in this film is through the roof, and only the most hardened of souls will emerge from the theater with dry eyes.

I don’t know if I have anything to offer that hasn’t already been said many times. There was a lot of irony in this film. With all the fan-service movies coming out these days, this movie was like anti-fan-service. I was a huge fan of the first Joker movie, and director Todd Phillips seemed to intentionally alienate fans of the first movie by turning the entire universe on its head. I went into the theater with an open mind. I hate to be critical of filmmakers when they experiment with new things, but it felt like Phillips was doing the Joker dirty because he didn’t want to make any more Joker movies, and making this movie in this way would guarantee that. Even with my low expectations, Joker: Folie á Deux was still a disappointment.

What a charming movie this was. Was it the best film of the year? Not by a long shot. That said, it did give me CODA vibes. I do not think it will shock the world and win Best Picture or even Best Screenplay as that movie did, but it did pack a nice emotional punch. The screenplay was well-written, and there was a lot of nice, subtle acting in the film, especially from Maisy Stella as Elliott and Aubrey Plaza as Older Elliott. Writer/Director Megan Park gave us an intimate and personal film about living as older people with the choices we made when we were young and how sometimes you don’t necessarily want what you think you want. Park added a nice bit of mystery in that Older Elliott tells Younger Elliott to stay away from a guy named Chad, but, despite her best intentions, younger Elliott falls in love with him, leading to a reunion of sorts between Chad and Older Elliott that is as heartwarming and heartbreaking a scene as you will ever see. The last 10 minutes of My Old Ass is a gut punch, and Plaza performs the scene brilliantly. This is a small movie that delivers big emotion.

This is one of the most entertaining films of the year. It’s about the last 90 minutes leading up to the first episode of Saturday Night Live, a seminal night in the world of television and pop culture. I don’t know how accurate the portrayal of the events is, but I do know that the acting is spot-on. Corey Michael Smith as Chevy Chase, Dylan O’Brien as Dan Akroyd, Matt Wood as John Belushi, and Lamone Morris as Garrett Morris perfectly channeled those individual personalities and idiosyncrasies in ways that brought those younger men back to life. Elia Hunt as Gilda Radner, Emily Fairn as Laraine Newman, and Kim Matula as Jane Curtain rounded out the not-ready-for-prime-time-players in ways that demonstrated those women’s talents, quirks and insecurities as talented women in what was a man’s world brilliantly. This movie channels SNL perfectly. It’s frenetic, edgy, and in your face. It pulls no punches and brings the laughs and entertainment in its own stylized way. Director Jason Reitman did the show proud.

It would be fair to say that the Autumn movie season has been a mixed bag. Some very good, some mediocre, and some downright bad films have graced the theaters. That said, there are some films coming out over the next few weeks that I can’t wait to see.

If you’re interested in hearing more about the films above, check out my podcast, Gen X v Z: A Movie Podcast. In it, I discuss these films with my film school graduate daughter. It’s available wherever you listen to podcasts.

“The Force is strong with this one.”