Can I refill your egg nog for you? Get you something to eat? Drive you out the middle of nowhere, and leave you for dead?

Screenplay by John Hughes

Can I refill your egg nog for you? Get you something to eat? Drive you out the middle of nowhere, and leave you for dead?

Screenplay by John Hughes

“You smell like beef and cheese. You don’t smell like Santa.”

Screenplay by David Berenbaum

I wrote this blog for Night Owl TV and it first appeared on their site on December 14, 2017. A link to that post and other Night Owl TV material can be found here.

“To my brother George, the richest man in town.”

By Brian Smith

With the Christmas season upon us, it seems only logical to combine a classic Christmas carol (The 12 Days of Christmas) with classic Christmas movies. The Christmas movie has become one of the most revered and profitable genres in cinema. It’s also become home to some of the most recognizable and beloved titles in the history of American Cinema. Many Christmas films have become a part of our cultural vernacular and movies that should really be considered Christmas-adjacent (I’m looking at you, Die Hard), can raise the ire of otherwise normal people if you dare to suggest that they’re not Christmas movies.

One thing that separates the great Christmas movies from the average to less-than-average Christmas movies are the strong thematic elements held therein. That’s not a terribly bold statement to make since that’s the case with most movie genres, however with Christmas movies it’s deeper. We blogged a couple of weeks ago about Miracle on 34th Street and how the idea of faith and what you can accomplish when you have faith is the real lesson behind that film. That thematic element is why that movie is so fondly remembered while other classics of the same period have been forgotten. Strong themes and big ideas give the best Christmas movies their individual spines and the strongest spines produce the best films.

Like any genre, Christmas movies are subjective. However, many people have their individual favorites that they watch every year. I too have Christmas movies that, if they go unwatched, it feels like something was missing that particular Christmas season. With that in mind, the following is a group of films that should be on your list to help get you in the mood for the biggest holiday of the year.

I’m sure you would have guessed that this film would be on the list, so here it is at the top. It’s easy to say that this film has become a cliché since its release more than 70 years ago, but pay close attention to this film the next time you watch it. It’s a Wonderful Life is truly an extraordinary film. Its main character, George Bailey (James Stewart), is one of the great heroes of American cinema. No, he’s not John McLane shooting up terrorists and rescuing his wife from the evil clutches of Hans Gruber. He is heroic in a smaller, but no less important way in that he puts everyone else’s needs and desires ahead of his own. He could have gone to college and traveled the world. He could have gotten in on the ground floor of plastics and made a fortune. He could have done anything in the world, but he stayed behind in the small town that he thought he hated, running his father’s business that he thought he hated even more, and he made a positive impact on the people of his town, and made all their lives better. The great thematic twist to this is that in so doing, he made his own life better too.

I spent an entire blog on this film a couple of weeks ago, so please reference that post for more in depth thoughts. But suffice it to say that this is the prototypical Christmas movie that tells us that having faith and believing in fairy tales are what make life worth living.

This film has been a staple in the Smith family home for a long time. While it celebrates all American holidays of the time, Christmas book ends the film. This film also gave us the iconic White Christmas song that is also a staple of the holiday season. And really, if the star power of Bing Crosby and Fred Astaire somehow aren’t enough to get you interested in this film, the comedic styling of Walter Abel as Astaire’s manager, adds a layer of depth and entertainment value to this film that make it essential holiday viewing.

Another Bing Crosby Christmas classic, this time he teamed up with Danny Kaye, along with Rosemary Clooney and Vera-Ellen to create one of the most iconic Christmas movies of all time. This is a terrific movie that has great singing, amazing dancing, is hilarious in parts, and is always touching. Directed by Michael Curtiz (Casablanca), this film has also become somewhat of a cliché. However, beyond those clichés it’s a movie about finding happiness and contentment in doing something wonderful for someone else.

Directed by the great Ernst Lubitsch and another holiday classic starring James Stewart, the storyline of The Shop Around the Corner will seem vaguely familiar to anyone who as seen You’ve Got Mail. Stewart plays Alfred Kralik, the top salesman in a Budapest gift shop, and has struck up a postal love affair with a woman he thinks he’s never met. Unbeknownst to him, the object of his affection is fellow shop worker Klara Novak (Margaret Sullivan) whom he cannot stand and who cannot stand him. Also starring the irascible Frank Morgan, this small and subtle film is about finding family and friendship in unlikely places, and how the Christmas spirit often motivates those discoveries.

Nominated for Best Picture, this underrated holiday classic is filled with laughs as well as heart. Cary Grant stars in this film as Dudley, a guardian angel helps people out in ways that they may not want, but desperately need. The Bishop’s Wife is a wonderful mix of comedy and drama that gives us a lesson we all need. That lesson is that we may think we know the path to happiness, but we’re usually proved to be wrong, and the path will come to us in ways we could have never expected.

Magazine writer Elizabeth Lane (Barbara Stanwyck) learns that being the perfect housewife is nothing like she imagined since it’s something she’s only written about and never experienced. She also learns that the best parts of Christmas, like the best part of ourselves, comes from what’s inside and not the superficiality of the outside.

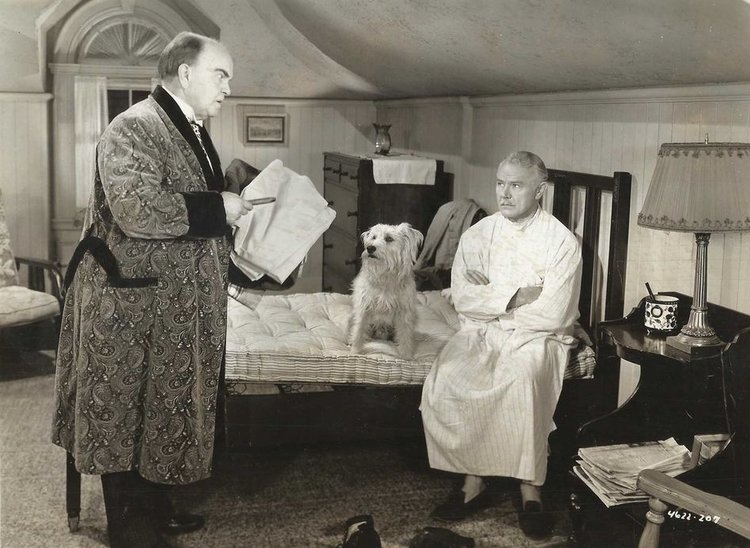

Charles Dickens first published his novella A Christmas Carol back in 1843. Since then there have been countless retellings of the story on stage and on the screen. The 1951 version is considered by many critics to be the best, but don’t sleep on the 1938 version. Both are faithful adaptations of the story, and are worth watching again because A Christmas Carol has become cliché as well. Seeing a faithful adaptation of it (or reading the novella) will remind you of why this has become such a timeless and iconic story.

A comedy with a serious point to make, It Happened on 5th Avenue looks at the serious problem of homelessness through a comedic lens. It also looks at the Christmas motif of sharing what you have with those who have far less than you. This is a fun and funny movie that on the outside looks like it’s a simple and shallow comedy, but on further inspection, has a deep and serious point to make.

This is a classic film that is probably more of a Christmas-adjacent film than a pure Christmas movie, but it does check a lot of the Christmas boxes. It’s also one of Judy Garland’s signature performances, so there are a couple of reasons to be familiar with this film if you’re a classic movie fan.

Yes, this film comes from a different era, but it is set in the 1940’s and it’s become as iconic a Christmas movie as any other movie on or off this list. It’s hilarious and heartwarming. It’s a movie that anyone who has pined for a Christmas gift that they know they’ll never get can relate to. And it tells us that Christmas is more than the gifts and the turkey. It’s about family and the memories that will last long after the outgrown toys.These movies have more to offer than entertainment value. They’re all highly entertaining, but the real gifts that these Christmas movies provide are the lessons that we can take from them. As Dr. Seuss says in How the Grinch Stole Christmas, “And he puzzled three hours, till his puzzler was sore. Then the Grinch thought of something he hadn’t before! ‘Maybe Christmas,’ he thought, ‘doesn’t come from a store. Maybe Christmas…perhaps…means a little bit more!’”

I wrote this blog for Night Owl TV and it first appeared on their site on November 29, 2017. A link to that post and other Night Owl TV material can be found here.

Edmund Gwenn and Natalie Wood in Miracle on 34th Street (1947)

By Brian Smith

Now that we’re past Thanksgiving and the Christmas season is in full swing, it’s time to start talking about Christmas movies. Watching Christmas movies, especially the ones that you’ve watched every Christmas for years, is as much of a holiday tradition as hanging the lights, decorating the tree, and buying presents for your loved ones. The holiday season just doesn’t feel complete if you didn’t make time to watch It’s a Wonderful Life, Elf, Christmas in Connecticut, Holiday Inn, or (for some people) Die Hard. Another movie that firmly belongs on that list is Miracle on 34th Street (1947).

It’s not necessarily my favorite Christmas movie, although it is close to the top. Rotten Tomatoes has Miracle on 34th Street as the #2 Christmas movie of all time, trailing only It’s a Wonderful Life. It was also nominated for Best Picture, and as this film celebrates its 70th Anniversary, it is apropos to run down a list as to why it might be the prototypical Christmas movie, and definitely is the most Christmassy of the Christmas movies.

Kris unites Macy’s and Gimbel’s for the Holidays!

As early as the 1940’s, commercialism had taken over Christmas. The holiday had lost much of its spiritual and religious roots and had become a holiday of gift-giving. The latest toy was on the top of the list of every child and the entire day could be ruined if that toy was not wrapped under the tree come Christmas morning. Or even worse, if the store didn’t carry what you were looking for, the salesmen may have pressured you into buying something other than what you came in for.

In Miracle on 34th Street, that’s where Kris Kringle comes in. Having worked his way into playing Santa Claus at Macy’s after filling in as Santa at the famous Thanksgiving Day Parade, Kris has no problem letting a customer know that another store is carrying the item she’s looking for as the most important thing is making her child happy. When the customer tells Mr. Shellhammer, the store’s manager, that from now on she’ll be a regular Macy’s customer, the capitalists (Macy’s executives) are put in the uncomfortable position of satisfying the customer’s needs, even if it means sending them to their competition. No less a person than R. H. Macy himself directs his employees to show that they care more for the customer and less for the profits (but will incidentally make more profits than they’ve ever seen). However, even that cynicism is trumped in the end when even Macy concedes that Kris is the real Santa Claus.

Kindness has overcome cynicism, and there is no message that has more Christmas appeal than that.

Edmund Gwenn won the Oscar for Best Actor in a Supporting Role for his portrayal of Kris Kringle, the kindly old man who convinces everyone that he really is Santa Claus. He is kindly to young Susan Walker (Natalie Wood), and opens up a whole world of imagination to her that had been shut off by her mother, Doris (Maureen O’Hara). While Doris’ intentions were good, Kris recognizes that they’re also misguided, and he does his best to show Doris and Susan that losing yourself in your imagination isn’t a bad thing. Kris also becomes fond of Alfred, the young Macy’s employee who loves to dress up as Santa Claus at Christmas.

It is Kris’ fondness for Alfred that causes him to become angry with staff psychologist Granville Sawyer (Porter Hall) when Sawyer misdiagnosis Alfred and gets him to believe that he has a guilt-complex and that he hates his father. This gets Kris to hit Sawyer over the head with his umbrella, and that sets in motion the events that lead everyone to believe in Kris. It’s a moment of anger that I can’t ever recall seeing by any other Santa Claus in any other production. Gwenn and Director George Seaton gave Kris Kringle depth of character and made him feel like a real person that we can relate to as an audience. They gave him a whole range of emotions and they made him vulnerable in ways that were physical as well as emotional.

Most Christmas movies do a great job of showing how wonderful Christmas is, but not many of them show the real-life struggle that parents must go through every Christmas. Whether it’s the challenge of being able to buy everything children want, or the struggle of perpetuating children’s belief in Santa Claus, Miracle on 34th Street peels back the curtain on the myths of Christmas and how important they are to perpetuate the holiday’s popularity. If kids stop believing in Santa, then what’s the point in hanging up the stockings? If they don’t hang up their stockings, why will parents buy toys for them? If they don’t buy toys, then the toy companies go out of business and thousands of people will lose their jobs. Yes, there is a magical quality to Christmas, but that magical quality holds up a practical world that would be devastated if the magic of Christmas were to somehow disappear. With that notion in mind, Christmas is a holiday for the imagination, as well a holiday for the practical. Finding that balance as a parent is challenging to say the least, and Miracle on 34th Street at shows that conundrum better than any other Christmas movie.

There are some genuine moments of comedy in this film and the comedy is clever and thoughtful. We’re shown that right away when Kris sees a shop worker putting together a Santa Claus display and then points out that he’s put the reindeer in the wrong order. The very next scene shows Kris discovering that the Santa Claus in the Macy’s Parade is intoxicated as the man comically tries to work the whip. There are many other legitimately funny moments throughout, like when Mr. Shellhammer gets his wife drunk so that she’ll agree to let Kris move in with them, only to have Doris’ plan break down when her next door neighbor Fred Gailey (John Payne) has already invited Kris to stay with him. Kris’ interaction with Sawyer is comic gold. The development of the District Attorney and Judge Harper and his campaign manager are gold as well. Having that balance of humor is important because….

Most Christmas movies have a lot of sentiment in them, and that sentiment quite often crosses over into the saccharine sweetness of schmaltzy. The humor does a lot to help that, but the very important messaging and thematic elements behind the story help to keep the sentiment from becoming too over-the-top. In that regard, Fred Gailey is the moral compass to this film, and he serves as archetypal Mentor to Doris, just as Kris is Mentor to Susan. Kris teaches Susan that imagination is important so that she can experience what being a child is really all about while Fred enlightens Doris that the power of faith can provide the strength to accomplish hings that would otherwise seem impossible.

Maureen O’Hara, one of the great actresses of the 20th Century, gave perhaps her signature performance in this film as the cynical mother who doesn’t allow her daughter to believe in Santa Claus, but discovers the power and value of faith. She also learns that sometimes faith can be more important and more powerful than common sense; that faith can give you the fuel to believe and accomplish things when common sense says that you shouldn’t, and you can’t! That character arc allows the audience to make the leap and at least consider that Kris could be who he says he is!

It isn’t just Doris however. As more and more people start to believe that Kris could be Santa Claus for all that he is doing and all that he’s providing for them, the audience is left to wonder at the end, could he be? It might not be possible, but in the universe of this film, it’s at least plausible.

One of the greatest things about Miracle on 34th Street is that everyone who deserves one, gets a gift. Even Kris receives a gift from Doris in the form of her belief in him. On its face that may be a small thing indeed, but it’s as important as anything to Kris. On the other side of the spectrum, Susan tells Kris that the only way she’ll believe in him is if he can get her a house for Christmas. Her belief wanes until the very end of the film when Kris has given them directions to get back to the city, and they happen to pass by the very house that Susan wanted and it has a “For Sale” sign in front of it. The film makers did a great thing by setting a standard that seemed impossible, but then made it come true in a plausible way that made sense.

All of the above points speak to the importance of this film’s theme. All Christmas movies have some sort of thematic element to them, but Miracle on 34th Street seems to have a lot of different thematic elements playing at once. Further, these themes complement each other rather than getting in each other’s way. Yes, Miracle on 34th Street is about overcoming the over-commercialization of Christmas, but it’s also about restoring faith. It tells us that faith is more than just believing in something. It tells us that having faith can give us the strength to accomplish things that common sense tells us would be impossible. It gives us a practical reason to have faith and shows us that faith can be rewarded in tangible and practical ways. That is the true lesson of this film. It tells us to believe in something. What’s more Christmassy than that?

“God bless us, every one.”

Screenplay by Hugo Butler, based on the novel by Charles Dickens

“Now I have a machine gun. Ho, ho, ho.”

Screenplay by Jeb Stuart & Steven E. de Souza

Emotion is the lifeblood of your screenplay. That might not seem like such a bold statement to make, but you would be astounded how many films are missing that key component. This is especially true in genre films, like action, horror and comedy. The writers of those scripts and the makers of those films are (understandably) more concerned with getting thrills, chills and laughs in their respective genre, so not a lot of emotional development occurs within the characters or the story. That’s usually fine for a genre film, because you’re going to see them precisely for the thrills, chills and laughs that they provide. However, there are some genre films that go the extra mile and do create that emotion. What I mean by that is that they provide emotional connections with the audience that turn them from good or even great action or horror or comedy films, into films that transcend their genre and become all-timers.

This idea came to me as I was listening to the Third and Fairfax podcast. This particular episode had Brian Gary interviewing Scott Frank, who most recently wrote and directed the Netflix series Godless, but has a long list of screenwriting credits, including Get Shorty, Minority Report, The Wolverine, and Logan. Over the course of the interview, he discussed how reticent he was initially to work on The Wolverine because he wasn’t a fan of comic book movies and really didn’t know a lot about them. It also seemed like he knew that they missed an opportunity with The Wolverine, so he was even more reticent to work on Logan, but he was given certain assurances about how the script could be written and how the film would be made, and he seems to be much prouder of his work on the latter film.

One word that Frank kept coming back to over the course of the interview, whether he was discussing The Wolverine and Logan or Minority Report or any other of his past projects, was the work emotion. Where is the emotion coming from? What set of circumstances in this story will get an emotional reaction from the viewers? For the character of the Wolverine, it was the idea of facing his own mortality. For Chili Palmer in Get Shorty, it was being a huge movie fan and getting a behind-the-curtain look at the business. For John Anderton in Minority Report, it was becoming a victim of his own program. What these films have in common is that they’re all genre films (Action, Comedy, Science Fiction), but they all were successful beyond their genre because the emotional component that was added to the film attracted a wider audience than just those who are fans of that particular genre.

I was thinking about this the other day as I was going through some of my old Best Picture blogs. There have been eight films that you could call either action or adventure to win Best Picture. Four of those winners came between 1995 and 2003 (Braveheart in 1995, Titanic in 1997, Gladiator in 2000, The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King in 2003). I wouldn’t actually call Titanic an action movie in the purest sense of the term. The first half of the movie is a straight drama, but once the ship starts to sink, it turns into straight action. Other action/adventure Best Picture winners include The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), Ben-Hur (1959), Lawrence of Arabia (1962), and The French Connection (1971). As I thought about the winners from the nineties and 2000’s, and then also about the earlier films, I realized that the one thing they all have in common is that, along with being spectacular action films, they all have emotional components to them that allow the audience to engage emotionally with the characters and really care what’s happening, as opposed to just being along for a thrill ride.

It really hit me as I was thinking about two films, in particular. The Return of the King is the final installment of the Lord of the Rings trilogy and there are several characters whom we’ve been following throughout the series. We’ve learned much about all of their personalities, their flaws, their fears, and their desires. For example, Frodo, the unlikely hobbit who’s tasked with taking the Ring to the land of Mordor in order to destroy it by casting it into the fires from whence it came, turns out to be a character of immense bravery and strength. He goes on this adventure reluctantly, and is always pining for home. Since hobbits are like miniature versions of humans, Frodo and his friends have a natural inferiority complex that leads them to believe they can’t accomplish as much as men. This inner struggle inspires the hobbits to excel beyond what they believe their limits are. When Aragorn finally accepts the crown to become the king of Gondor, the hobbits all bow before him, and in one of the most emotional moments of the series Aragorn says to them, “My friends, you bow to no one.”

Speaking of Aragorn, we learn early on that it was his ancestor, who generations earlier, was unable to destroy the ring when he had the opportunity to do so, and that led to his downfall. Aragorn fears that since the same blood flows in his veins then the same weakness may also. He is reluctant to take his rightful place in the world. That very human trepidation that Aragorn has creates an emotional bond with the audience, even though his issues are fanciful to the rest of us. None of us are ever going to become king, but all of us have felt some unease about our place in the world or in our profession or in life in general. Many of us may even feel unworthy of what our destinies may be, and that lack of self-worth holds us back, just like it’s held back Aragorn.

Braveheart is the other example. Mel Gibson directed and starred in this film about a simple Scotsman who ended up leading a revolution against the British king. William Wallace (Gibson) wants nothing more than to raise crops and a family, but that all changes when the woman he loves is killed by the English soldiers occupying his town. From that point on, the movie is filled with blood and carnage and adventure, but the first 40 minutes of this film are spent allowing us to get to know William and his love Murron and his friend Hamish (Brendan Gleeson). We get to see their relationships develop and we get to see the bonds they have with each other, and we care about them. We have an emotional attachment to them.

The other action films on his list have many of the same components, whether it’s Judah Ben-Hur being betrayed by his childhood friend, T.E. Lawrence proving to the generals and to himself that he’s a good soldier, or Maximus avenging the brutal slayings of his wife and son, we care for and root harder for these characters because of that emotional component.

If you are working on a screenplay and you believe that emotional component is missing, try one of our coverage services at the link here, and we can help you find the emotional key that will unlock the emotion in your story and open it up to a wider audience.

I initially wrote this blog for nightowltv.com and it first appeared on November 2, 2017. Click the link for more from them.

1964 was a good year for cinema. Goldfinger, arguably the greatest James Bond film of all time, was released during the year, as were several other classics and borderline classics like A Fistful of Dollars, Marnie, Zulu, The Night of the Iguana, and A Hard Day’s Night. There were three films that were all nominated for Best Picture, that rise above every other film released that year. Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb is one of my personal favorite films, and the film that I would have voted for had I had a vote for Best Picture in 1964.

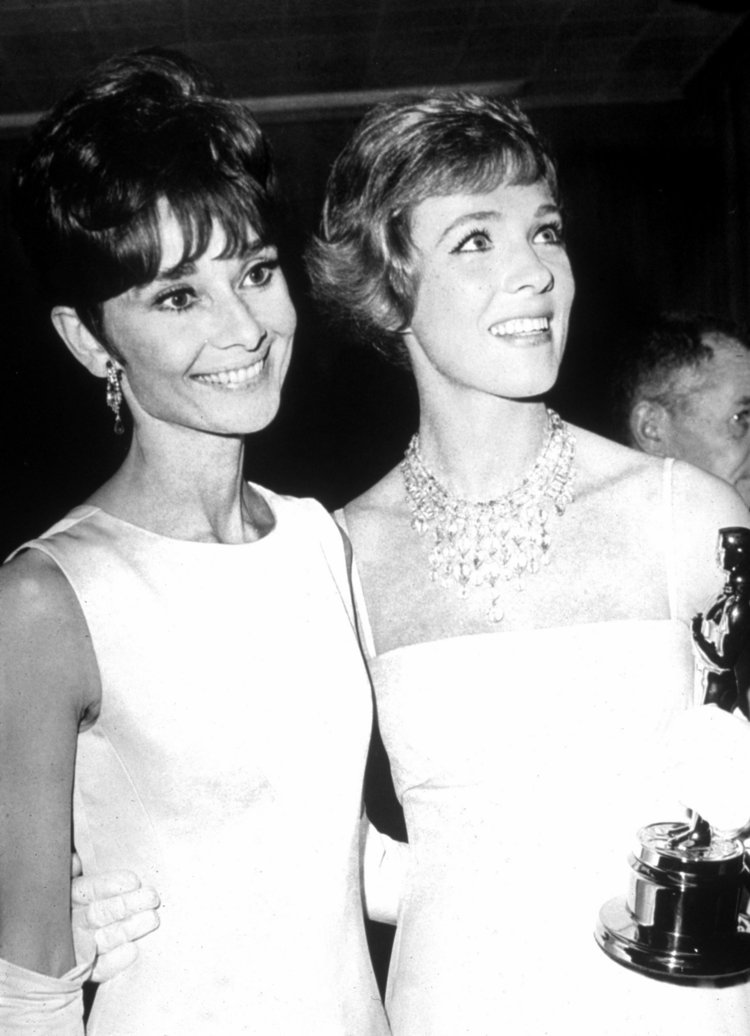

The other two films were musicals, and both are considered to be among the greatest musicals of all time. My Fair Lady had a very good Oscar night taking home eight statues out of 10 nominations, with wins for Best Picture, Best Actor (Rex Harrison), Best Director (George Cukor), and others. Mary Poppins wasn’t far behind with five Oscar wins, including Best Actress (Julie Andrews), Best Song (Chim Chim Cher-ee) and Best Music.

Yes, My Fair Lady won Best Picture, and yes, My Fair Lady is on the AFI list of the Top 100 movies of all time, coming in at #91 and Mary Poppins is not on that list. However, interestingly enough, Mary Poppins is ranked higher than My Fair Lady on AFI’s list of the Top 100 Musicals of all time, coming in at #6 vs. #8.

Agreeing with the latter assessment, I am here to tell you that Mary Poppins is a better movie than My Fair Lady and it was the best musical of 1964. Here are five reasons why that’s true.

There is no question that in 1964 Audrey Hepburn was a huge star, having already starred in such iconic films as Breakfast at Tiffany’s, Roman Holiday and Sabrina. Julie Andrews had made a name for herself playing Eliza Doolittle in the Broadway version of My Fair Lady, but Jack Warner wanted a star for My Fair Lady, and Julie Andrews had not starred in a feature film at that point. There were few stars bigger than Audrey Hepburn, and her grace,charm and wit certainly helped make Eliza Doolittle into one of the most beloved and recognizable characters in the history of American musicals. The problem I have is that Hepburn didn’t do any of her own singing. She could sing and was reportedly furious when she was told that her voice was not strong enough to do the singing for the picture. While her overall performance is terrific, the fact that the studio wouldn’t let her sing is a major issue, in my opinion, since singing is such a huge component of her character.

On the other hand, making her big screen debut and earning a Best Actress Oscar in the process, Julie Andrews turned the role of Mary Poppins into one of the most iconic characters not only in the Disney roster, but in all of cinema. This role would also give Julie Andrews one of the most successful screen careers of the second half of the 20th Century. Walt Disney reportedly could not listen to her sing Feed the Birds without being moved to tears, and her renditions of Spoon Full of Sugar, Jolly Holiday, and Supercalifragilisticexpialodocious along with Feed the Birds showed a range of singing, acting and dancing that Hepburn simply could not match. Andrews could be equally charming and stern. Not only that, but the character of Mary Poppins is a stronger, more confident driver of the action, whereas Eliza Doolittle mainly reacts to things happening to her.

Give me Julie Andrews over Audrey Hepburn in 1964 every time.

Both films showed somewhat misogynistic men overcoming their old fashioned ways to discover their priorities had been completely askew. I would argue that the character growth of George Banks is more profound and more sincere than the growth and change of Henry Higgins. The thing is, Higgins starts out the film as a total cad. He is an arrogant, smug, cocky jerk who gets his kicks out of messing with people’s lives. By the time he gets his act together and realizes that he’s in love with Eliza, I personally couldn’t care less whether he ends up with her or not. Eliza, for her part does want him, but she deserves way better. Once the story is resolved, there is no emotional impact.

George Banks, on the other hand, doesn’t necessarily start out Mary Poppins as the most likable character, but he’s at least doing what he ought to be doing, or what he thinks he ought to be doing to take care of his family. He later discovers that he’s missing out on the most important and most rewarding parts of being a father if he doesn’t change his ways. In what is some of the most emotionally impactful story-telling I’ve ever seen, George Banks becomes the father that he never knew he could be.

My Fair Lady has some great and recognizable songs like The Rain in Spain, I Could have Danced All Night, and Get Me to the Church On time. The top songs from Mary Poppins were mentioned above, but there are other memorable numbers like Stay Awake, Sister Suffragette, Step in Time. . What separates the songs in Mary Poppins versus My Fair Lady is that the songs from the former do a better job of moving the story forward or showing character. In fact, Bert, the chiminey sweep (Dick Van Dyke) uses the Spoon Full of Sugar reprise to finally show George Banks how he’s missing his children’s childhood, creating a moment of catharsis for George. The same argument could be made that Henry Higgins has a similar epiphany when he sings I’ve Grown Accustomed to Her Face. But, I think, like almost everything else in this film, it takes too long and is too drawn out to the point where boredom overcomes any dramatic impact that’s being made.

Both of these films are long. Mary Poppins comes in with a running time of 139 minutes, so it’s a little more than two hours. My Fair Lady comes in at a whopping 170 minutes, just 10 minutes short of three hours, and takes too long to get moving. While there is a lot of singing and character exposition, we’re a good 40 minutes in before the story really gets going. The length of the film has a negative impact on the drama in the story, and I find myself just not caring about the characters. Mary Poppins, on the other hand, is 30 minutes shorter and has a much tighter story that is paced better and doesn’t give us the same kind of long gaps in story points that cripple the story in My Fair Lady.

Piggybacking on the previous point, Mary Poppins is just a more entertaining film than My Fair Lady. It has a better story-line, it has better songs, and it has better pacing. It also has characters that we care about more than we care about the characters in My Fair Lady. It has better art direction, and it casts a much wider net in terms of cinematic techniques and language. Mary Poppins is a veritable smorgasbord of film making styles and techniques, using animation and cutting edge special effects to help enhance the story. Mary Poppins is a feast for the eyes as well as for the heart.

“Faith is believing in things when common sense tells you not to. “

Screenplay by George Seaton

“Six bucks and my right nut says we’re not landing in Chicago.”

Screenplay by John Hughes